We find ourselves in a bewildering world. We want to make sense of what we see around us and to ask: What is the nature of the universe? What is our place in it and where did it and we come from? Why is it the way it is?

To try to answer these questions we adopt some “world picture.”

—Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time

I’ve been reading Philip Pullman again, and reading as much as I can find of what he alludes to in the course of his stories. Among the books Dr Hannah Relf lends to young Malcolm Polstead, our protagonist in La Belle Sauvage, is A Brief History of Time, which exists in our universe as well. While I enjoyed The Body in the Library by a parallel Agatha Christie, presumably, which is the first book he chooses to borrow from her library, it’s the world picture conjured up by Hawking–and not the specific account of space-time so much as the idea of a “world picture” as such, as a way to answer fundamental questions–that has led me to think about Pullman’s project anew. After all, one of the first, unforgettable images from The Golden Compass is literally the picture of a world, another world visible in the aurora, projected from a lantern slide; and some of the final images in The Rose Field… well, we’ll get there when we get there.

Sometimes it becomes possible for an author to revisit a story and play with it, not to adapt it to another medium (it’s not always a good idea for the original author to do that), nor to revise or “improve” it (tempting though that is, it’s too late: you should have done that before it was published, and your business now is with new books, not old ones). But simply to play.

And in every narrative there are gaps: places where, although things happened and the characters spoke and acted and lived their lives, the story says nothing about them. It was fun to visit a few of these gaps and speculate a little on what I might see there.

As for why I call these little pieces lantern slides, it’s because I remember the wooden boxes my grandfather used to have, each one packed neatly with painted glass slides showing scenes from Bible stories or fairy tales or ghost stories or comic little plays with absurd-looking figures. From time to time he would get out the heavy old magic lantern and project some of these pictures on to a screen as we sat in the darkened room with the smell of hot metal and watched one scene succeed another, trying to make sense of the narrative and wondering what St. Paul was doing in the story of Little Red Riding Hood—because they never came out of the box in quite the right order.

I think it was my grandfather’s magic lantern that Lord Asriel used in the second chapter of The Golden Compass. Here are some lantern slides, and it doesn’t matter what order they come in. – Philip Pullman, the “lantern slides” edition of His Dark Materials

While most people I’ve talked to have expressed disappointment with the ending of The Book of Dust, and that was my own initial reaction, I’ve found it is growing on me with rereadings, particularly as I’ve been listening to the audio versions read by Michael Sheen. It doesn’t hurt that his interview with Pullman, accompanying the final volume, is the best of its kind that I’ve found so far. Particularly resonant are their discussions of the procession and the story, commenting on a little demonstration or rhetorical flourish of Pullman’s in another interview, a video for the Bodleian Library; and of the alethiometer contrasted with the myriorama as images of reading and writing or telling stories.

So it strikes me that the first requirement of a compelling world picture–speaking only for myself–is that it should partake of that commingling of beauty and truth which Keats’ Grecian Urn attests. If in time irradiating its truth-beauty some contradiction should arise in our perception of that dear picture between the sense of its truth and its felt beauty, then we have to either discard it–Lewis has written powerfully about that in The Discarded Image–or, recurring again to Keats, we can abide with it at the limits of our “negative capability.”

This is where I strive to engage with Pullman, rather than rejecting him, believing us “capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason,” as he himself has pointed the way, having these very lines quoted by another one of his scholars, Dr Mary Malone, in The Subtle Knife. When I think of his work as a kind of invitation to think and feel in this way, its challenges, while no less agonistic and at times agonizing, take on a beautiful, sporting quality. And like few other authors, Pullman conduces to the “having of wonderful ideas,” in Duckworth’s model for learning, and to “the realization that prayer consists of attention,” in Weil’s formulation, which I take to be an end beyond the end of learning for its own sake.

One thought I’ve been noodling on along the way, which I’ll just lay down as best I can for now, is that language–language learning at the most basic and most advanced levels alike, literacy and reading of all degrees of interpretive complexity, and literature at its furthest avant garde edge–seems to live and move and leap ahead by way of play.

To adduce a handful of instances representing the movement between world-pictures and worlds:

- Homeric games and the bow-stringing challenge

- David dancing before the Lord; dance for Huizinga “the purest and most perfect form of play that exists”

- Caedmon’s Hymn, considered the first English poem, and the story of its composition given in Bede

- Chaucer’s pilgrims, making of their tales “ernest” and “game”

- Shakespeare’s wandering players and kings and the “invention of the human” (Bloom)

- Joyce’s “shout in the street” in Ulysses, and its echoes back in Araby

- Morrison’s Playing in the Dark and her acceptance of the Nobel, of the full weight of history

If these are the leaps that come to mind, still there are immense degrees of nuance in between each of them. Between Shakespeare and Joyce, a fair amount of literature survives. Or to zoom in further: between Keats’ vision of (his Bright star‘s vision of)

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores

and Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach with its “melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,” and the near-contemporary Oxford Movement; or between Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell and Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, and Byron pushing at the boundary of reason with no little energy, with Mary Shelley producing Frankenstein as a byproduct of their play; or to jump ahead, within the work of a single writer, from Nabokov’s “link-and-bobolink,” “the correlated pattern in the game,” in Pale Fire to his Terra and Antiterra in Ada, where the “game of worlds” becomes almost literal; so much of any writer’s work which we still read seems to consist in the give and take between modeling and effacing world pictures.

And it seems like this is always including, if not in fact by way of, metaphors of play.

Where they get especially ambitious–or playful–writers absorb scientific and religious worldviews alike into their imaginations. Spariosu has given a much fuller treatment, and Sloek a much richer theory, but there is Kierkegaard’s interpretation of Don Giovanni; Bakhtin’s reading of Rabelais; Dostoevsky’s incorporations of scripture, and Bulgakov’s rewritings of it; Vonnegut’s invention of Kilgore Trout, or Milosz’s Bruno; John Crowley’s other worlds; Pullman’s, and his sprite-like narrators…

I’ve tried to stick to the English language, but translations have crept into my magic circle, as literature itself wouldn’t mean much in any language without the likes of Homer, the Bible, Shakespeare, and Dostoevsky connecting ideas to images, but also helping their readers with the task of making connections between ideas and action, and thus knitting together the inner world or life to the outer, even up to and including that “consummation devoutly to be wished,” though Benjamin asserts that the storyteller is as much generated by as generating death, “death of the author” be darned.

Still, the question arises–the one Hawking asked back at the start–of what world picture or model best facilitates such summing up of the incommensurables, the infinitesimals, or which anyhow values it as an endeavor worth attempting, whether we have the language to express it or no. And it is a question to which in these posts I am continually responding, and trying to understand others’ responses.

For me, this has to include the roots of the language, religious and scientific and poetic alike. Caedmon has to be there, as well as Hawking, and Christie to help us solve the mystery. Then, perhaps with a little help from our friends, we can also better parse the world-pictures that assail us on the screens that surround us, like this one:

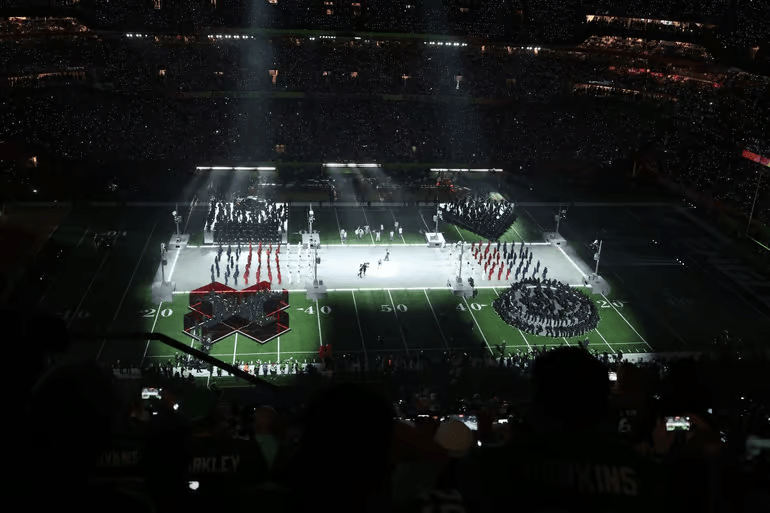

Just now hearing about this eruption of PlayStation iconography at last year’s Super Bowl halftime show by Kendrick Lamar, for example, and about shadow boxing from Babcock, so we’ll see if we can collaborate to write something about that. Or the great chess scenes in Nabokov or The Wire:

And I still haven’t read the large claims of the likes of McGonigal and Combs for the ameliorative power of games, nor Bogost on their rhetoric and persuasiveness, nor Miller on the theology of the same.

Looking next time, though, at Kendrick Lamar’s design patterns, with some serendipitous discoveries in Ortega y Gasset, starting with “The Sportive Origin of the State” (Translated into English; original Spanish) via Postman’s Technopoly (and footnoted in good old Homo Ludens to boot).