I did not expect this to be the Limbus Company chapter I would write about first…

…But I want to talk about Ryoshu’s story.

Content and Spoiler Warnings

OK, you know the drill, but it should all be said up front.

- Limbus Company is a really dark game, and this is a particularly dark chapter in it. We are going to be discussing some really grim subject matter, including: Domestic/Child Abuse, graphic, gory violence, suicide, rape, and murder. Just for starters.

- We’re going to talk about some major plot and thematic elements, so that means we’re going to talk spoilers about Limbus Company’s Canto IX and its preceding chapters, the source material (Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s “Hell Screen”), and, while we’re at it, some Shakespeare stuff. (I have a point, I promise…)

I should, stress, though, that I’m not here to relish the grim themes or make connections to contemporary circumstances, as I often have in the past. I’m in academic genre-interrogation and art vs. commerce mode, because I think Limbus Company has done something odd, interesting, and new with this chapter. So as much as I’m throwing up the content warnings, really this isn’t about the horrors of modern life.

Except insofar as it might be about compromise and conflicting realities.

Which is as good a place to start as any, I suppose.

Limbus Company’s Identity Crisis

It is weird to think that I’ve put more hours into Limbus Company than any other video game ever made (1,366 hours, according to Steam), and yet it’s probably my least favorite of Project Moon’s offerings. Lobotomy Corporation and Library of Ruina seemed like miracles of purpose to me: efficient, direct, and calculated; while at least 700 of those 1300 hours playing Limbus Company were probably spent on nothing-burger alternate game modes or leveling up characters, or accidentally leaving the game on while I was eating dinner or grading or something.

We’re coming up on the third anniversary of its release—I’ve spent three years playing this game every day. Every day I’ve logged in, probably twice on most days, just to collect daily rewards so I can keep my characters leveled for the next big story chapter. And this means that Limbus Company has become part of my life—I have habits built around the game. Not terribly intrusive habits, but habits nonetheless.

This is a weird choice for a horror game. Or a game that’s ostensibly a horror game. Horror—especially the psychological horror Project Moon excelled at evoking with Lobotomy Corporation and Library of Ruina—is a tightly-controlled, intense experience that has to be carefully designed to succeed. And here’s Limbus Company asking me to log in and level up my characters, run through the same encounters over and over again, and reduce the levels that used to be intense and terrifying to rote and mundane exercises I conduct while Bob’s Burgers plays in the background.

I can see two reasons for this.

The obvious reason is financial. Korean gacha games are big business, and you can make a lot more money selling microtransactions to whales than you can selling full games at a fixed price. I’ve absolutely spent at least three times as much money on Limbus than Library and Lobotomy put together, so that tracks.

The artistic reason, though, is difficult to justify. Project Moon has always trafficked in the “horror become mundane”—Lobotomy Corporation was literally about managing nightmare monsters on a rote, day-to-day basis, and the growing, gnawing horror of trying to keep the engine running while everything spins out of control, over and over again. And Library of Ruina was also about a world where murder, horror, and psychological damage had become commonplace. So you could argue that Limbus Company is just the next logical step in the theme—by making the horrors of the game habitual, the player becomes complicit and fully immersed in the nightmare-world.

But that’s not how it works. On a day-to-day basis, we are not exposed to some fresh hell; we just go through the motions until the next chapter comes out, at which point the game becomes thrilling and grim and horrifying again. If anything, the horror of the new chapter is undermined by the familiarity with the systems and the work we’ve done to over-level our characters.

The first chapters of Limbus Company felt, properly, like we were underpowered little weaklings taking on powers far beyond our ken—because the challenges we faced seemed monumental for our scruffy, underleveled characters, and we had to figure out how to distribute those scanty first few weeks’ worth of resources as efficiently as possible to get through the story.

Now, after three years of consistent logins and hoarded resources, the new chapters remain challenging and threatening, but artificially. My once-scruffy little band of misfits has now toppled empires and taken down terrifying monsters. Those major challenges of the beginning of the game have literally become weekly training sessions. I’m not drastically underleveled, asking myself questions about whether or not I’m prepared for this fight, but quite confident that I have all the tools I need, and can get past virtually any challenge by strategic tinkering with my party composition, or by carefully observing the enemy behavior, or by just getting lucky with the RNG. Even when they drop some out-of-my-league threat into a battle, I can’t help but think “Oh—I’m supposed to lose this fight.” Or: “I guess something scripted will happen to make this winnable.”

This does not make compelling horror. And it is a far cry from the serious escalating threats of the past games.

Keeping Everyone Happy

But there’s another, more insidious decision that is especially relevant to our subject today.

Along with the diminishing returns of the rote, daily/weekly gameplay, there has been a persistent tendency in the story to provide satisfying, cathartic conclusions to every new chapter.

That does not sound like a bad thing at first blush, but let me explain.

You know how in The Empire Strikes Back there’s this tough, downer ending: Luke failed to rescue his friends and got his hand cut off when he faced his father. Han was captured and frozen in carbonite. You’re allowed to end a sequel like this only when you know you’ve got more story to tell (and that you’ve got the ability to tell it). Without the promise of Return of the Jedi, this would never have been an acceptable way to end the story.

The same could be said of Avengers: Infinity War or Spiderman: Across the Spiderverse—both have downer, setback endings—and are relatively effective and surprising—but promise a more complete, positive catharsis in the true ending to come.

Limbus Company, however, is structured in such a way that makes this very difficult to do. Since each chapter focuses on one (and only one) of the game’s twelve characters, and since it doesn’t seem likely that we’ll be able to revisit any of those characters in any real depth after their chapter concludes, the game feels practically obliged to give each character a satisfying, cathartic (and positive!) send-off at the end of each chapter. Yi Sang makes peace with his past, Ishmael achieves her revenge, Don Quixote (read: Sancho) recommits to her dream, and Hong Lu ends his family’s tyrannical succession of greedy leaders. Limbus Company reads less like a finite movie series, and more like a sitcom setup: eventually, everything has to go back to status quo for the next chapter.

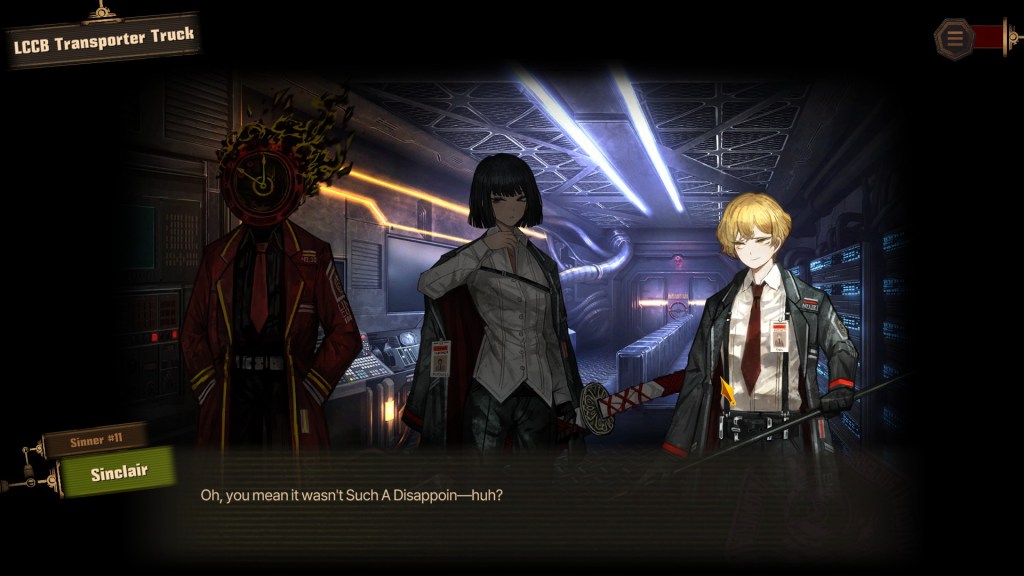

There are exceptions, and significant ones—Gregor, Rodion, and Sinclair (each of the first three characters from the release season) each have complicated endings with unfinished business. Honestly, when I first played through those chapters after the initial release of the game, I figured we would be revisiting these characters in multiple chapters, and was a bit surprised when Yi Sang completed his arc in the first additional season. But of the chapters since, the only seriously unfinished business (besides the villains joining the Blue-Reverberation-esque Nine Litterateurs) is Heathcliff’s commitment to “Remember” the otherwise obliterated-from-reality Catherine at the end of Canto VI. And both Gregor and Sinclair get major character development moments in this new chapter, bringing them closer to the other characters’ completed arcs.

But these exceptions serve only to highlight my point. The game is structured in such a way that Project Moon feels compelled to provide a happy, satisfying ending for each character at the end of each chapter. And that is very bad news for your horror game. If happy endings are not only possible, but mandatory, it’s really hard to keep up that grim, nightmare-of-the-mundane tone that has characterized all of the games to this point.

Especially if your source material didn’t have a happy ending in the first place.

Hong Lu, A Dream of Red Mansions, and Canto VIII

So I’m no scholar of A Dream of Red Mansions, but I did read it a couple years ago to catch up on Limbus Company’s source material, and I liked it and remembered it well enough to see much of what Limbus Company did with Hong Lu’s chapter last spring. And, overall, I think it was another faithful adaptation of the book’s themes, with some fascinating transposition to Project Moon’s world—which I could say about most of the past chapters. I liked it a lot, in short. And in a vacuum, I would not really venture to criticize.

But there is one thing that stands out, especially when discussed in this light.

Where the original classic was about a powerful family (and an era of beauty) falling into decadence and decay, Canto VIII of Limbus Company re-frames the story as the new generation destroying the old and bringing about new hope for the future.

Again, that’s fine. I’m totally on board with this shift: it’s faithful to the themes of the original, while staying true to the characters that have been developed in the game. It makes sense in the world, and appropriately adapts the setting and themes of the original work. There might even be a greater thematic (and even political) statement about historical narrative-making that I’m not able to fully appreciate. (Was the era to come really so bleak and disappointing?)

But the move is toward the happy, satisfying conclusion. Just like how Ishmael manages to actually kill the whale in Canto V (achieving closure) or how Don Quixote accepts her dream (and optimism) in Canto VII. Where tweaks occur, they are directed toward the aim of a happy, satisfying conclusion. Grim, ambiguous endings now become just a little more pat and crowd-pleasing.

And that’s kind of frustrating, considering how grim and ambiguous the endings of the two prior games turned out to be. It feels a bit like Project Moon has gotten soft in its old, decadent age—fat and happy on microtransaction money, they feel more obliged to keep pleasing the crowd and make fans happy—where once they would throw real risk of failure at the players or strip accomplishments of their catharsis in the last moments of a story. What I loved about those games was that they were not routine and predictable, and found greater truth as a consequence. But now that Limbus Company’s gameplay is designed to be rote and predictable (for that sweet, sweet microtransaction money) at the same time the story also tends toward the rote and predictable (lest we alienate the fans), I find that I’m growing progressively less invested in their more recent work.

And Then There Was “Hell Screen”

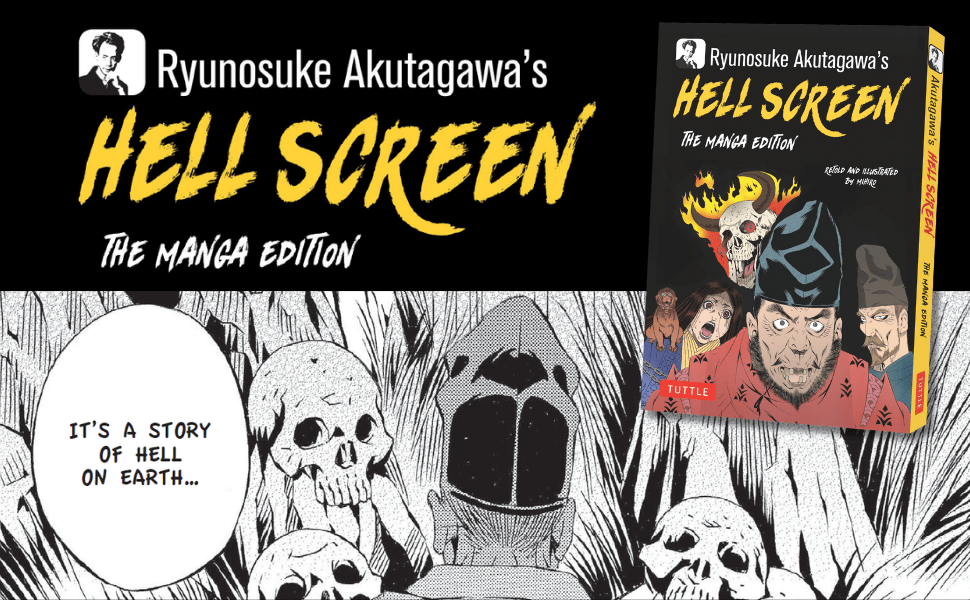

But if you thought A Dream of Red Mansions had a downer ending, “Hell Screen” is a whole ‘nuther problem entirely.

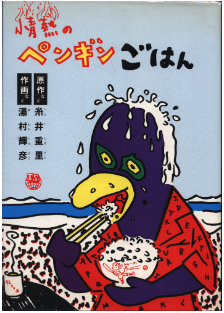

“Hell Screen” is a short story by Japanese writer Ryunosuke Akutagawa, who also wrote “Rashomon” and “In the Bamboo Grove”—the two stories that Kurosawa borrows in his famous adaptation of Rashomon. If you’re familiar with the movie, you can probably guess that we’re dealing with a writer of nihilism and the macabre.

But you really have no idea.

“Hell Screen” is about a fictional painter named Yoshihide. Yoshihide is the most skilled painter in all the land, but he is arrogant and perverse, preferring to draw scenes of devils and monsters and horrors than calm landscapes or austere portraits. He is reviled by his community every bit as much as he is respected for his craft, so he becomes a bitter, angry man. And the only thing he truly cares about is his beautiful daughter. So much so, that even when his daughter is courted by “His Lordship,” he is too jealous and protective to allow this advantageous match.

Then “His Lordship” hires Yoshihide to paint a screen depicting the eight hells of Buddhism. Initially, his work is very successful—Akutagawa details at length the horrifying gothic images that Yoshihide produces. But Yoshihide is unsatisfied, and cannot complete his work. He protests that he can only paint what he has seen, and needs a true vision of hell to complete his work. He demands to see an aristocratic carriage, with a beautiful woman inside, burned before his eyes so he can include it in the painting.

The climactic scene has Yoshihide painting the horrific scene only to realize that “His Lordship” has chosen his daughter as the beautiful woman in the carriage, burning to death according to his own twisted request. In the final paragraphs of the story, the author intimates that Yoshihide finishes his work with unprecedented artistry, but hangs himself immediately afterward.

Yeah.

I was blown away by this story the first time I read it. I really didn’t know what to expect from Akutagawa, and while there’s plenty to compare to other gothic horror storytellers like Poe or Gogol, Akutagawa’s brutality and nihilism in “Hell Screen” remains a standout characteristic of his work, even compared to the Western masters. But for Project Moon, this was A CHOICE. If Project Moon wanted to continue their selection of existentialist anti-heroes (like Meursault, Sinclair, and Raskolnikov), they could have easily picked one of Mishima’s heroes (either Honda or Kiyoaki from The Sea of Fertility would have made excellent choices), or we could have gone with a hero from a national epic (like Dante, Odysseus, Don Quixote, or Hong Lu/Bo Jia) like Genji of The Tale of Genji. But nope—we picked Yoshide from one of the most depraved and upsetting horror stories I’ve ever read. Even among the other stories by Akutagawa, there is a cruel, uncompromising vivacity about this story and its ruthless, relentless horror.

And I absolutely love that choice. I can’t help but think that Project Moon’s horrific world (known only as The City) must be inspired by Akutagawa in some way. And including Yoshihide seems to be a testament to that inspiration, just as I imagine that Yi Sang was included as a way to hold an influential (and personally-inspiring) Korean writer up to the world stage.

Three Years of This…

I don’t know what the original design document for Limbus Company looked like. I can only speculate. I don’t know what voices were involved in the decision-making process from the initial concept to the game we have now.

I suspect that, with Limbus Company, Project Moon wanted to make a more ambitious game—and a more lucrative one. I suspect that the team wanted to cash in their popularity and good will with their fans and make something that could catapult them into wealth and success beyond the scope of their earlier, smaller projects. I get the sense that Lobotomy Corporation and Library of Ruina were both megahits in Korea, well beyond their original expectations, but never really managed to turn that popularity into financial success.

Limbus Company, therefore, has always read to me like a compromise, even from its first days. The promotional material in those first weeks after its announcement—the website and art and character design and worldbuilding—are all pure Lobotomy-Corporation-era Project Moon. But the implementation—the gacha mechanics and daily rewards and half-baked multiplayer—read like something alien: trend-chasing by a team that doesn’t have the fluency in game design that Lobotomy Corporation and Library of Ruina—by accident or design—routinely demonstrated. Limbus Company in its first days was a horror game bolted onto a gacha game (or vice-versa), presumably as a way to turn fans into whales and earn all the money.

But, as the man said, “the medium is the message.” And the horror game has, pretty inevitably, become a gacha game first and foremost. And while horror games are designed to unnerve and disturb, gacha games are designed to encourage players to spend more money with the promise of power and stability. Eventually, the horror story must necessarily make concessions to the monetization scheme, and your original designs must bow to your financial aspirations.

And maybe nobody notices at first. Maybe you can go two years and more with the story you envisioned only making some small concession to the financial scheme you’ve chosen. Maybe it doesn’t matter when you give Hong Lu or Ishmael a more satisfying ending than would be appropriate for them. Maybe you get away with a “to be continued” on Heathcliff’s story, preserving its grimness. But I suspect we now have to talk about two Project Moons: the Writers and the Accountants—and the distance between them has never been more obvious.

Because you can’t turn “Hell Screen” into an emotionally-satisfying, happy ending. You just can’t. Did you read my synopsis? Holy crap.

So what do you do, then? What do you do when the Writers planned a chapter that disturbs, horrifies, and careens out of control, while the Accountants demand that your wild chapter work within the established structure?

Again, this is all speculation. I don’t know what’s going on in Project Moon’s offices. I don’t know if there are factions, or what their priorities are.

This is what I do know:

Canto IX is a radically different beast from its predecessors. Much about this chapter represents a huge deviation from what I’ve come to expect from Project Moon in its other updates.

But the ending is not different.

And that’s what makes this all so interesting.

At Long Last, Ryoshu and Canto IX

Canto IX opens faster, quicker, and meaner than any other chapter I’ve played in this game. One consistent critique of Project Moon’s work is that it is “overwritten”—we spend hours on circuitous exposition and information dumps to set up the big emotional catharses: much of which could be eliminated for the sake of pacing, and which could be discovered through gameplay or character beats.

NOT A PROBLEM HERE.

We are dropped directly into the action: Limbus Company is attacked by a group of renegade syndicate leaders. Our character rush back to HQ only to find the whole facility obliterated, familiar characters dead and dying, and our hard-won golden boughs stolen. The perpetrators are an unprecedented coalition of syndicate (organized crime) leaders from each of the five “fingers” established in previous chapters (and games, for that matter). And each of these syndicate “nursefathers” was once Ryoshu’s master, in a childhood she can only remember fragmentarily.

Look, this is great storytelling even by Project Moon standards. It seamlessly integrates combat encounters into the development of the story, and some of these revelations even happen in-combat, with new characters appearing to fight our team unexpectedly—which efficiently and propulsively moves the plot forward with every encounter. We do get a couple over-long exposition dumps once we find the survivors of the attack, but we quickly embark on another unprecedented choice: the team is split up, and you have to manage smaller teams of three or four members rather than your full complement of sinners. Which is also brilliant, as this choice takes a lot of control away from the player and forestalls familiar strategies and combinations.

It’s also thematically appropriate: Ryoshu is famously curt and hostile, even to the point of abbreviating familiar phrases with initial letters (which Sinclair often has to translate)—so a chapter that dispenses with the exposition in favor of getting straight to the killing makes perfect sense here.

What we get here is Die Hard-style gritty action with clear motivations and plain-spoken plotting. We’re introduced to a finite roster of villains, all of whom have to be dealt with, and all of whom have distinct, unique characters. There are twists and turns as villains reveal new agendas and heroes develop new powers, all of which make for a thrilling ride, start-to-finish. It’s masterfully paced, confident and straightforward. I love it.

But we gotta do that emotional catharsis thing. Ryoshu has to face her past. We have to walk through the beats of the source material, in addition to all our action-movie heroics. And this is where things get complicated.

So Ryoshu is a Black-Widow-style assassin raised by a unique collaboration of syndicate nursefathers for reasons initially unclear. Each syndicate is represented by one of the fingers on the human hand:

The Thumb is hierarchical and aggressive, demanding proper respect and propriety from members and victims alike.

The Index is tightly wound and controlling, taking incontrovertible orders from a mysterious authority (which is explored in detail in Library of Ruina).

The Middle is emotionally explosive and vengeful—the sinners antagonized a high-ranking officer of the Middle and he’s been a recurring villain since.

The Ring is artistic and grotesque, regarding violence and cruelty as an aesthetic enterprise (Ryoshu often refers to violence in these aesthetic terms, dispassionate to the point of sociopathy).

And the Pinky is…well, largely unknown. Our first encounter with agents of the Pinky occurred in Hong Lu’s Canto, where it is revealed that they are working behind the scenes as spies to usher in their own inscrutable order. There they were benevolent (or at least aligned with our interests). Here, not so much.

Because, it turns out, the Pinky nursefather was the most abusive to Ryoshu, despite the fact that she (the nursefather) was her biological mother.

When Ryoshu escaped from her surrogate parents/mentors/captors, she wounded each one with the sword she no longer unsheathes. In the case of her Pinky nursefather (yes, I realize how ridiculous this sounds every time I write it), she cut out her tongue as a kind of symbolic rejection of her hateful emotional abuse.

Which makes it all the more surprising when Ryoshu discovers this same person masterminding the attack on Limbus Company, still able to talk.

The Emotional Stakes

That’s all well and good for plotting, and sets up a pretty great Kill-Bill-esque revenge story, but there’s one more Kill-Bill-style wrinkle.

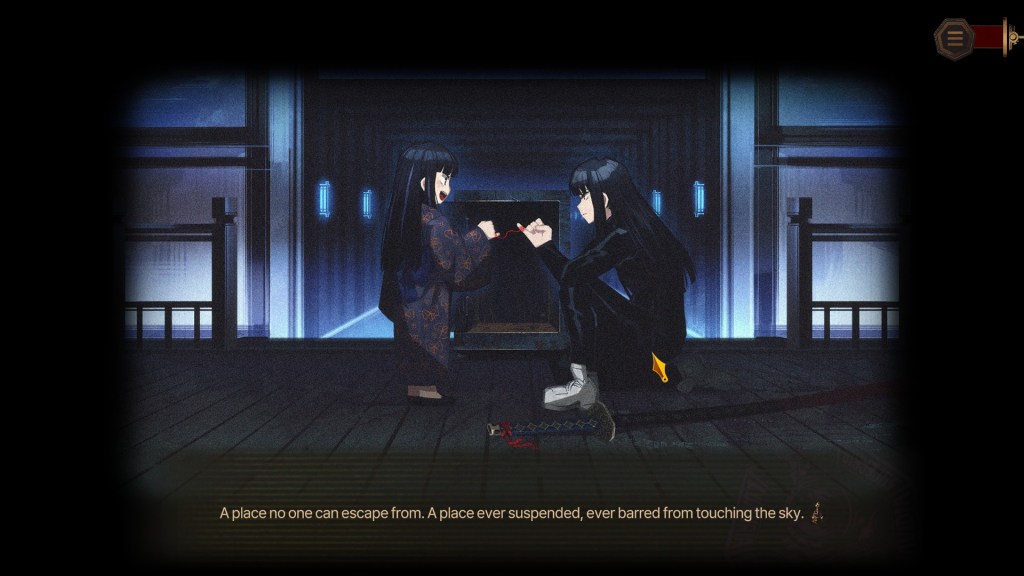

Ryoshu had a daughter.

Adopted daughter, admittedly, but—as in “Hell Screen”—the only person Ryoshu cared about. It turns out that much of Ryoshu’s behavior is explained by her relationship with her daughter. Why is she called Ryoshu instead of Yoshihide?—her daughter mispronounced her name and it stuck. Why does she abbreviate words?—she and her daughter used to do this as a game (noteworthy, then, that Sinclair, the most childlike sinner on the team, is the one who can translate). Why did Ryoshu betray her mentors and escape the House of Spiders?—to protect her daughter from Ryoshu’s own fate, being turned into a weapon of the syndicates. Why did Ryoshu join up with Limbus Company?—to infiltrate the House of Spiders and rescue her daughter from the time-stasis safe where Ryoshu hid her. And why doesn’t Ryoshu use her sword out of its scabbard?—because each cut of the sword cuts away part of her memory (hence the amnesia) and she does not want to forget her daughter.

But it turns out that it’s all too late. Ryoshu’s daughter, tired of waiting, emerged from the safe and was, predictably, adopted and trained as an assassin by the nursefathers, unbeknownst to Ryoshu. Worse, she now wears the garb and veil of the Pinky nursefather—the same malevolent abuser whose tongue was cut out by Ryoshu years ago.

Which would have been nice to know before Ryoshu exacts her vengeance and runs her through with her sword.

Oops.

As an adaptation of the beat in the original Akutagawa story, this does the job reasonably well. Like Yoshihide, Ryoshu inadvertently kills her own beloved daughter—here in a lust for vengeance rather than artistic inspiration—but all the “painting” metaphor is here in the Ring’s aesthetic-critical language. It’s a convoluted revenge story rather than a barebones gothic horror setup, but it’s an appropriate adaptation with Project Moon’s typical aplomb. So far so good.

But now what?

Ryoshu, monomaniacally obsessed with finding her only-beloved daughter, accidentally kills her in her lust for vengeance—that’s the kind of serious character development that pitches her way out of the game’s gacha framework. The game even addresses this—you literally lose control of Ryoshu for the duration of the next battle because she has turned into a mindless destructive (and self-destructive) force. Dante even muses that she might very well leave the team altogether—she no longer has any reason to stay.

But the Accountants say she’s got to. We’ve got a status quo to get back to, after all.

So Ryoshu, enraged to the point of insanity, unsheathes her blade and wields it in a whirlwind of blows—obliterating her opponents and her memory at the same time. Here is our big emotional catharsis: Ryoshu’s big transformative moment—and the Mili song starts to play…

But it’s…wrong…

That’s not what this moment should sound like…

Mili and the Music of Project Moon

This is hard to explain in prose, but I’m going to try anyway.

Lobotomy Corporation used unlicensed, free-to-use music. It worked, but it didn’t work well, and it makes the game’s soundtrack a bit of a strange hodgepodge if you’re trying track down its most effective tracks. But I’m guessing that this was one of the first things Project Moon wanted to fix when Lobotomy Corporation made a bunch of money.

So Library of Ruina has two soundtracks: Studio EIM does most of the score-work, making brooding ambient music for your battles and story beats, while Mili—an indie Japanese group—writes and performs several important tracks for the big emotional catharses. When characters literally transform or reach major realizations; when they distort into monsters or overcome their horrors, a Mili song plays. It’s a big moment, and the music signals how big the moment is—like when you’re fighting a Final Fantasy boss and the Latin chanting starts up.

But Mili songs tend to be haunting and discomfiting. They’re talented musicians with a pretty strong command of a variety of genres, and Library of Ruina makes full use of that with a warped love song, and haunting piano number about loneliness, and a creepy electronica jam to symbolize the calculating machinery of the Index’s commanding computer.

In Limbus Company, this translates to one Mili song per chapter. Sinclair got the bleak and haunting “Between Two Worlds” for his battle with Kromer the anti-mechanization human monstrosity, Yi Sang got the inspiring “Fly My Wings” for his apotheotic rejection of his invention’s misuse, and Ishmael got the alien and cryptic “Compass” for her battle in the belly of the whale. Perhaps the high point so far has been Heathcliff’s “Patches of Violet”—a mock duet between Heathcliff and Catherine where each blames his/herself for the failure of their relationship against a tortured string solo. It’s gorgeous and heartbreaking and perfect.

And when you’re in one of these climactic battles, with the big emotional stakes on the line and one of these jams kicks in—that’s why I keep coming back to this game, for three years, every time a new chapter shows up.

But, considered another way, this is just another predictable component of the overall Project Moon apparatus—another constant at odds with the variable horrors of this game. Another level of coordination for the Accountants to work out in advance. Another fixture to please the fans. Another thing our Writers need to consider as they put together their Art.

Let’s Read That Again

Bear with me, because maybe we’ve been going about this all wrong.

What if this isn’t a calculated masterpiece of purpose, deliberately blunt and curt because it fits our blunt, curt character.

What if the Kill Bill parallels are not incidental—a testament to the chapter’s tight plotting—but blatant homage, just short of plagiarism.

What if this is the slapdash chapter, put together at the last minute, half-assed and broken.

What if we didn’t do exposition dumps or character beats because we were rushing this crap out the door and we just had to finish it.

What if the reason why it isn’t overwritten is because it isn’t finished—at least, not the way it was supposed to be.

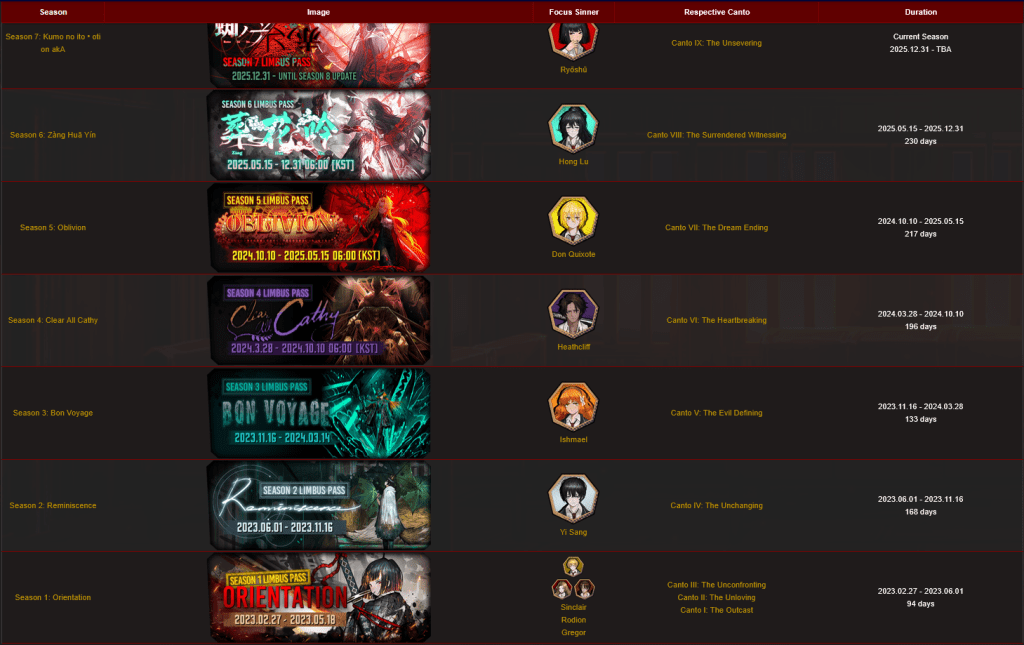

Video game release schedules are messy, messy things—as often as not subject to delays and setbacks and God-only-knows what kinds of unforeseen problems. And Limbus Company has been habitually bad about their release schedule of new chapters. The first new “season” after the initial release was just over three months after the launch, June 1st of 2023. The second was released well over five months later, in November. And I recall the developers apologizing profusely about the delays. They even stopped scheduling releases at that point, preferring to announce the new chapters only a week or two in advance in an “it’s finished when it’s finished” sort of way. In 2024 we got Heathcliff’s chapter in late March (roughly four-and-a-half months later) and Don Quixote’s in October (six-and-a-half months after that).

Which brings us to Hong Lu’s chapter in May of 2025, seven months after the last chapter.

And, of course, Ryoshu’s chapter, released seven-and-a-half months later on December 31st of 2025. Seriously. On the day. New Year’s Eve.

What’s more, each season/chapter since Heathcliff’s had been accompanied by two “Intervallo” chapters—fun little side stories that play with the game’s genres, characters, and world and keep the game going—while Hong Lu’s season/chapter had only one (and an Arknights crossover which cannot be replayed).

There’s a lot to like about Ryoshu’s chapter, and I don’t apologize for my praise. Nor do I have any problem with the long gaps between new chapters—I’d rather they take the extra time to do each chapter properly, even if it means only one release each year. But I suspect this game’s ballooning budget and ambition—with each new chapter taking longer to produce than the last—finally got burst here. I suspect the Accountants finally put their foot down. There was no way they were only going to release one chapter this year. They were going to get the second under the wire come hell or high water.

Ryoshu’s Redemption

So there’s Ryoshu, a whirlwind of steel, driven to madness by the mistaken murder of her own beloved daughter, tormented past the point of sanity and human tolerance—and the Mili song kicks in and it’s…

…a gentle piano piece about proving that she can love.

The ghost of her daughter passes beyond her spinning blade and convinces Ryoshu to rejoin the party of sinners, even though she no longer has any memory of this daughter. The blade is sealed into the scabbard by a red string—the same symbol of belonging and family ties that was used to connect Ryoshu to her daughter before (but it’s also the same symbol used to describe her ties to the abusive nursefathers – another fraught connection the game passes over without comment).

The game proceeds to a final confrontation against the Index nursefather. Win, and it rolls credits—the same “Pass On” song each character has sung so far. Like SAIKAI, the gentle Mili song, it’s gentle and maudlin and maybe even a bit sickly-saccharine and…wrong. But it also features a segment where Ryoshu sings against a music-box rendition of her daughter’s voice, a mechanical reminder of her loss and a hint that Ryoshu, too, is just going through the motions. Perhaps it highlights Ryoshu’s disaffection and disconnection—while the music soars, Ryoshu fails to emote, her voice methodically hitting each note with monotone, robotic precision.

And right at the end she sighs, just before the last line: “It’s alright.”

“I.A. (It’s Alright) because I can L.O. (Live on…?)”

And I don’t know how to feel about any of this.

There’s a good story here, and plenty of support for the themes of cyclical generational violence, finding compassion and love for flawed family members, and there are real, evocative and loving depictions of Ryoshu’s relationship with her daughter. And some of these are rooted in the original Akutagawa story as well.

But I wanted rage. I wanted screaming to grip my soul. I wanted a metal ballad unleashing every ounce of Ryoshu’s torment—and Project Moon can do that: Gebura’s theme in Library of Ruina expresses that sentiment pretty perfectly.

The source material, and even the text of the game present a story of an unfathomable horror; a woman destroying everything she was raised to become even as she destroys herself and her only-beloved daughter—she transforms into a weapon whose sole purpose is obliteration, unleashed upon the world by the monstrous criminals who created her.

But the tone tells me that All is Well. Every aesthetic choice in the staging of this big, cathartic finale assures me that the status quo has been well and thoroughly restored.

I just don’t believe it. Not one bit.

And I can’t tell if that’s the point.

All’s Well That Ends Well…Right?

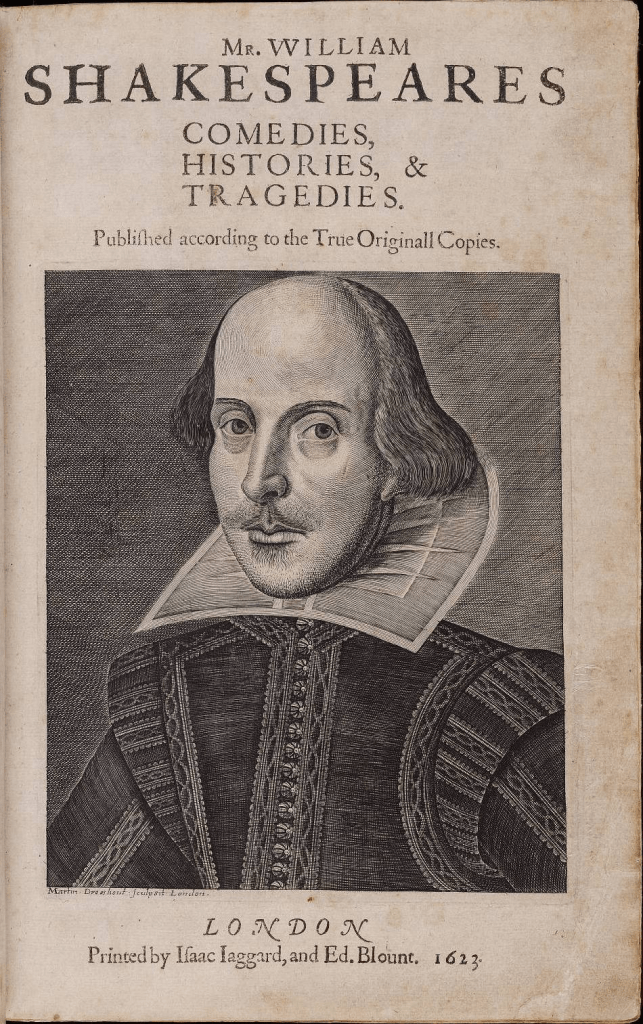

I don’t talk about Shakespeare enough.

Like, the guy is such an incredibly talented writer, and has produced dozens of plays so artistically powerful and influential that we basically attribute the current state of the entire English language to his writing. And even if that’s overstated, you just read his work and it’s clearly the product of mindblowing talent.

I’m sure part of the problem here is overexposure: they force Romeo and Juliet down the throats of every American high school student whether they want it or not, and you’re sure to get one of the “four great tragedies” before you leave, too. Shakespeare is so “important” that it’s easy to forget that he’s also just a straight-up amazing writer with incredible range and human insight.

But if I ever do write some monograph on Shakespeare and how great he is, I’m probably going to give all those “great tragedies” a pass. I love Hamlet and King Lear, don’t get me wrong, and you can sell me on Macbeth, too, but they don’t fascinate me like some of Shakespeare’s other work.

See, I love the weird stuff. I love his dark comedies, like Measure for Measure or The Merchant of Venice, or the wonky genre-bending retellings of old stories, like his mean-spirited take on Troilus and Cressida. If I were to talk about one of the “great tragedies,” it would probably be the ever-taboo Othello—not because of the racial angle, but because it’s a comedy gone wrong, and I’m all about that.

I like broken things. I don’t know why this is, but I do. I can absolutely appreciate a flawless masterpiece like Hamlet or King Lear (or even Romeo and Juliet, understood as a breathless hormone-driven comedy of errors with tragic consequences). But I like it when the artistic seams show and I can pick at the scabs of bad ideas. I like ambitious works that go wrong and genre Frankensteins, whether or not they’re successful.

And among these broken genre experiments is All’s Well That Ends Well.

In All’s Well That Ends Well, Bertram (who is kind of a prick) is on his way to France to seek his fortune when Helena (who is in love with him, as only Shakespeare heroines can love) decides to follow him and seek his hand in marriage. But Helena is low-born, an orphaned daughter of Bertram’s family doctor, and Bertram is the son of a countess, and won’t have her—even after the King of France commands them to marry. Instead, he takes off for the war in Italy, where he meets and falls in love with Diana. But when he goes to sleep with Diana, Diana and Helena pull the ol’ bed trick and switch places, getting Bertram to consummate his marriage to Helena without his knowledge. Bertram returns home after Helena fakes her own death, woos another nobly-born lady, and is interrupted again by Diana and Helena. Helena reveals she is not dead, reveals that she has deceived Bertram into their marriage, and the King of France re-confirms their marriage in the final page—though both Bertram and Helena seem to have misgivings at this point. All’s Well That Ends Well.

Bullshit. And Shakespeare knows it.

I definitely forgot many of the details before re-visiting the play for this essay, but I remember my initial reaction clearly: Shakespeare is deliberately writing an artificially-pat ending, well in line with the conventions of the comedy genre (everybody’s gotta get married at the end), but defying its spirit. Even the title: “All’s Well that Ends Well” is a kind of bitter challenge.

Is it Well? Really? Even after all the deception and intrigue and manipulation? Isn’t this just a bit…you know…rape-y? Isn’t this marriage kind of doomed to fail?

I’ve never seen the play performed—unsurprisingly, it’s not well liked—but I also have to wonder if it just works better on the page than the stage. Any actor’s performance will necessarily bring an answer to what appears to be a question on paper. Their reactions will determine whether the King’s choices are justified or not. And the real challenge in the performance would probably involve preserving that ambiguity.

And I have to imagine this is also on Shakespeare’s mind. You know, late Shakespeare. Coriolanus Shakespeare. “Why do I keep writing masterpieces for these damn plebs” Shakespeare. Everybody wants a new comedy for the season but Shakespeare already wrote Much Ado About Nothing and As You Like It and Twelfth Night goddammit so he basically flips off the audience with a Measure for Measure or All’s Well That Ends Well. On the one hand, this reads as a genre subversion—an intentional effort to push the boundaries of what is possible and accepted in Elizabethan comedy; on the other, this reads as a push back against the expectations of audience and commerce alike—an expression of Shakespeare’s frustration with the constraints on his Art.

Ryoshu’s Happy Ending

I don’t think there’s anything resembling emotional consistency about the ending of Ryoshu’s chapter in Limbus Company. I’m not going to pretend that this is all intentional, and that Project Moon are secret geniuses trying to play the tone of the Mili song against the actual text of their story for some deeper artistic purpose. I think it’s more likely that they commissioned the Mili song before the writing was done, because the Accountants were busy kicking this turd out the door as quickly as possibly while the Writers were desperately trying to make something truly good out of it, with what little time they had. Or that the Writers wanted something really raw and unsettling for the big Mili song and the Accountants vetoed it because they didn’t want to drive away any of the whales they’ve amassed through three years of unprecedented popularity. Or, heck, maybe there was just miscommunication between Mili and the Project Moon team. Or maybe it had nothing to do with Mili at all because the Writers couldn’t agree on what they wanted to do with the Accountants’ deadline looming over them. Or maybe some writers insisted on a pat ending and others subverted it with some key decisions. I don’t know for sure, and can only guess.

What I know is that All is NOT Well. And I’m pretty sure at least some of the writers know it.

Much as Ryoshu’s ending is pat and cathartic, it also stands in contrast to some major tension with the other characters. For the first time ever, one of the sinners was completely incapacitated for the final battle: Gregor apparently went full bug-monster and you even have to fight him in what is probably the roughest battle of the chapter. He is also conspicuously absent from the final slide displayed over the end credits (another first).

Meanwhile, Sinclair goes full super-sayan with an identity that teases his future fusion with Abraxas, the cryptic god of Hesse’s Demian. We’re assured that this is only temporary—we may never see this version of Sinclair again—but it’s a heck of a beat all the same, and seems especially appropriate in light of his affinity for Ryoshu.

There are a lot of daring choices made in this chapter, and I support them whole-heartedly. And, what’s more, I have to wonder if these choices are metatextually deliberate. Here I am talking about the possible factions at Project Moon, and the text of the chapter itself emphasizes the breaking up of the Limbus Company team into smaller factions. The sinners are, like any beloved band, starting to break up. Gregor’s got personal problems interfering with his life; Sinclair’s growing up and thinking about a future solo career.

We’ve only got three sinners’ chapters left in Limbus Company. The game might well be over by the end of 2027. So now’s as good a time as any to start breaking the toys we’ve devised and upending the game’s status quo. And maybe Project Moon is starting to have some tough conversations about the future. The gacha model implies a kind of game-as-service approach, with content releases stretching indefinitely into the future; but the horror story Project Moon is telling is very finite. And I stand with the Writers (as I imagine them). I don’t want the game to go on forever. It will be better to resolve these plot threads, and let these characters reach the end of their arcs, as they are with Gregor and Sinclair here. I would rather have a finished game to revisit and replay than feel obliged to keep logging in and leveling up my characters ad infinitum.

I look forward to the end.

But as for Ryoshu, I find myself unsettled.

For the first time since the game began, I am deeply uncomfortable with their adaptation. I feel like a serious breach of faithfulness to the source material has been committed. I feel like I’ve been fed a cheap catharsis rather than a meaningful look at the very real horror both story and game have concocted. I’ve been robbed.

But, in being robbed, I also feel a deeper connection to this game and this series than I have in a long while. At last, the game has become truly unsettling and horrifying again. Even as the game assures me that All is Well, I know that it is not, and even feel a bit offended that someone might suggest as much.

And the real, lurking horror of it all lies in an uncertainty I haven’t felt in a while.

Do they know?

Are they planning to fix it?

Or is this half-baked compromise a real part of the text, now?

Are we stuck living with a brain-damaged Ryoshu, and a writing team who is willing to call that cathartic closure?

Or is this a deliberate misdirect—all part of some enigmatic master plan?

Or am I missing some cultural nuance, some important detail in the Korean text or cultural associations that makes clear what I only infer?

Which seems most likely?

On Wellness

Though it was not my intention to make them, there are greater connections to be made. There is certainly a greater thesis here about the ways that we are assured by the modern world that “All is Well” when it isn’t. How once-reputable organs of journalism like the New York Times tiptoe around the chaos surrounding the Trump presidency like his violations of constitutional rights are legal curiosities, or how corporations continue inundating us with promises about AI while astute investors worry about an impending economic collapse, or how publicity releases from major movie studios blithely promise profits to investors and bright futures to fans while the entire industry collapses in on itself under buyouts and the threat of AI replacing writers and other artists. We are repeatedly assured that “All is Well” because the Status Quo is a far more profitable state of affairs than panicked uncertainty about the future—which is where most of us actually seem to be. And that disjunction—between the terrifying reality we’re all stuck living in and the assurances of normalcy we are surrounded by—just makes our horrors even more crushing.

And, in a sense, Ryoshu’s chapter speaks deeply to all of this. Ryoshu is not well. Ryoshu never could have been well. She is deeply damaged by a childhood full of horror and abuse. She has been turned into a tool of destruction for the purposes of insidious masters. And she destroys herself in this chapter, as utterly and completely as if she were written out of the game altogether. But she isn’t. The game must go on. We will have our catharsis, and our Mili song, and her deadpan rendition of “Pass On,” and she will show up in our roster for Shadow Dungeons and Luxcavations, just like she always has, because the game must go on. This dramatic plot development cannot interrupt the day-to-day grind of the game I (and all the whales) play habitually.

But this is not in the text of the game. One must read against the grain of the tone and many of the artistic choices to reach these conclusions and connections. Because the game assures us that All is Well, even when what we’ve experienced is Not At All Well. It speaks to our disassociation from reality not because it depicts this dissociation, but because it is, itself, dissociating from its own reality. Tempting as it may be to credit Project Moon with intentionality—surely they did this on purpose; this was the whole point!—we must resist: “the confusion is on purpose” is just another form of the statement “All is Well,” and contributes to the same delusion. (How often are we told by Trump supporters and conspiracy theorists that “it’s all part of the plan”—as though Trump, like God, “moves in mysterious ways…”) What we see is not the subversive artistic clarity of someone like Shakespeare, pushing back against genre conventions, but the push-pull of conflicting priorities within a single company: a narrative struggling against itself.

Instead we must respond with brutal clarity. No, we must say. Ryoshu is Not Well. Any more than Yoshihide is Well at the end of “Hell Screen”. But at least Akutagawa has the decency to confirm Yoshihide’s Not-Wellness. Akutagawa’s horror is straightforward: a terrible thing happens to a terrible person and we are encouraged to feel revulsion and discomfort. We are meant to walk away unsettled, and to reflect on the injustices and horrors of our own lives. Even Shakespeare wants us to walk away from All’s Well That Ends Well challenged and unsettled. There is catharsis in this, even if it isn’t explicitly positive: a validation that our lives are prone to these kinds of horrors and injustices.

But Project Moon (and here I speak of the whole company—the finished product they’ve produced instead of the disparate component voices I’ve identified) does not. Even if some of the writers and developers are defending the artistic integrity of their work, Project Moon has delivered us a messy, possibly unfinished chapter, confused in its messaging, but clear in one single-minded intent: We are meant to keep playing. And I will, because I’ve invested myself deeply in the game and I am curious about its uncertain fate. And because I trust those artists who have guided me through ten years of rich games, and know they are there still, working toward the ending they envisioned years ago.

But I will also not forget.

Ryoshu is Not Well.

And, it seems, neither is Project Moon.