The Definitive Book of SNES RPGs (Vol. 1) by Moses Norton and A Guide to Japanese Role-Playing Games by Kurt Kalata (ed.) are both published by Bitmap Books, new within the past month and last few years, respectively. They are doorstoppers, beautifully produced, quite pricey, and worth every penny. My name appears in the acknowledgements of the former; many of my favorite games–EarthBound/MOTHER 2, Chrono Trigger, Xenogears, Wild Arms, and so on–appear in the latter, though each game is afforded only a page or two due to the book’s massive scope.

I’ve long dreamt of writing a book like these, a kind of Haunted Wood for video games, but I haven’t actually played all that many of the incredibly rich and diverse body of games that Norton and Kalata cover. Particularly, I’ve wished I could better understand my favorite games of the golden age of console RPGs in their cross-cultural context, having tried, so far with little determination and less success, to learn Japanese for that purpose–so I’ll settle for reading others who can, for now.

A few disclaimers up front: I am aware that Moses and the Bitmap folks have faced a smear campaign and waves of cancel-cultural recrimination over comments he made, but I will step around that. This choice, like the review which follows, is, needless to say, not entirely unbiased by my personal friendship and professional respect for the writer also known online as The Well-Red Mage, nor my admiration, shading into jealousy, of the productions of the Bitmap team and writers of Kalata’s clout who have worked with them. But what’s an amateur Video Game Academy scholar to do? We have to talk about the games themselves, first and foremost, in all humility and giving grace as far as we can, extending the circle of dialogue, lifting up the voices of students, fellow hobbyists, fans, content creators, and industry professionals alike. None of us is perfect, none of us ought to feel we’re in a position to cast stones, in my view; with all deference to the righteous Redditors and other pharisaical denizens of the retro games discourse, I can’t see who is helped by such a pile-on. Or, if that disputed passage in John’s gospel is not to your taste, let’s say it in Dostoevsky’s terms, from Alyosha and Grushenka’s tete-a-tete in The Brothers Karamazov, with a Sakaguchi spin: I’m all for giving an onion (knight), giving a second chance or New Game Plus, once someone has apologized. I can only offer an apology of my own to whoever has been harmed by the exchange and its fallout. Certainly I wish Moses and his family the best after the wringer they’ve been through, and hope that Vol. 2 of his book is not too long in coming, whether from Bitmap or another source if they’re not able to patch things up.

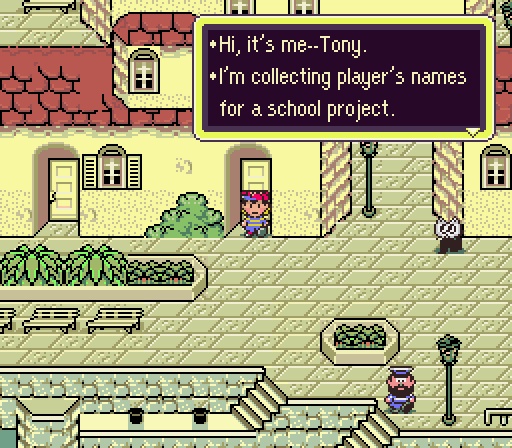

But without further ado. Per the title, and in line with its author’s long-time, courageous project of bringing greater objectivity and rigor to the discussion of widely beloved games from ye olde eras past, The Definitive Book of SNES RPGs (not only JRPGs, mind, as I initially thought) takes as one of its points of departure “a new systematic approach to defining an indefinite genre” (31). I found this section powerfully clarifying, as I tend to have a much more intuitive, wishy-washy stance on questions of categories and sub-genres. Norton lays out a practical “Rule of Three: Character, Combat, Narrative” with each of these further breaking down in to three elements: Roles, Progression, and Statistics for Characters; Combat as such, its Turn-Based mechanics, and Variables; and Narrative story arcs characterized by Economy and Exploration. Where two of the three larger headings overlap, or where an RPG is more heavily weighted towards one or the other, we get the sub-genres of “action” or “adventure,” or indeed “action-adventure,” but any game that has at least some significant elements of narrative, combat, and character development can be fairly called an RPG (37).

Ranging over the 22 games this rubric brings under discussion, covering the first half of the SNES RPG library’s alphabet, Norton’s analysis is anchored by these mechanical considerations–and isn’t it refreshing to see how he chooses to cut across the usual distinction between gameplay and story, opting instead for this powerful, flexible Rule of Three? Each chapter opens with a graphic indicating which elements are deemed to be in evidence, alongside the developer and publisher credits, and while plenty of the games have all nine icons, there are a handful of edge cases. “King of Dragons isn’t an RPG! I can hear you yelling” he remarks in the penultimate chapter; to which I have to reply, demurring, “I’ve never even heard of it” (501). And in fact these debatable RPG inclusions, especially ActRaiser and EVO, make for some of the most interesting chapters in the book in terms of defining what an RPG is, and what a particular blend of mechanics, story, and gameplay loops portends for thematic questions about the meaning of a given game as a work of art.

For, as even a cursory reader soon discovers, dipping into chapters here and there rather than plowing through the book cover to cover as I did on my first read (though I heeded Norton’s caveat to go out of ABC order so as to flip-flop Dragon View and Drakkhen,”the first SNES RPG” 302, and one with a fascinating lineage that may or may not intersect with Gary Gygax himself), the close analysis of game elements in line with a wider project of empirically defining the genre is only one of the book’s significant threads, and perhaps not its most important. Just as Narrative and Combat are mediated by Character, Norton’s own voice, experiences, predilections, and indeed his character are present throughout the discussion. Along with the requisite historical context, pertinent information about the games’ development and systems, and more or less entertaining trivia and Easter eggs, we get a personal tour of each game’s world, its challenges and triumphs, and reflections on all of it from a true connoisseur.

For me, the best sections of the book weren’t actually the ones about the best games: the tour de force of Chrono Trigger or the ebulliently playful-yet-earnest EarthBound (which I read and commented on for the author in draft), or the groundbreaking FFII or even the operatic FFIII; nor was it, on the other hand, Norton’s almost impossibly judicial, admirably evenhanded treatment of the execrable Lord of the Rings. Much as I appreciated these for how they provide wonderful, coherent perspectives on games I know and love (or rather hate, in the case of the SNES LotR, as one can only hate a missed opportunity, a fall as profound as that from a Melkor, brightest of the Ainur–Tolkien’s text–to a Morgoth, archfiend and all-around jerk–its SNES adaptation), I find myself thinking most about, and flipping back to most often, the Introduction and the chapters on the Breath of Fire games.

The Foreword by Alex Donaldson, co-Founder of RPG Site, does a solid job setting the tone, and it is probably noteworthy that both he and Moses Norton are mixed race authors writing authoritatively, confidently, and joyfully about an industry where people of color are not always represented. Norton’s Introduction grounds the book in his upbringing in Hawaii, and he makes explicit the connection between his Native background, his longing for home, and a Tolkienian sea-longing most memorably expressed in great art, which combine to convey the importance of nostalgia in his conception of quality video game critique and analysis. This is all very much catnip to me, preaching to the choir if you like, just as much as his wise words about the meaning of an ostensibly silly game like EarthBound call and respond across the distance to concerns I’ve written and thought about for years, here and on sites run by Norton himself. In sharp contrast, really, to the more technical discussion of the Rule of Three, though both the technical considerations and nostalgic themes become integral to the chapters that follow, this is a big swing of an Introduction after my own heart. If I hadn’t known Norton already beforehand, I’d have reached out to him on the strength of the opening few pages, because I recognize here “a friend I’ve never met,” to use the Pauline (EarthBound’s Paula, that is) locution, a fellow aficionado of 199X RPGs.

In the chapters on Breath of Fire and its sequel, the book’s throughlines of biographical experience and nostalgic retrospection come together in what for me were the most illuminating fashion with its other core thread of systematic, definitional concerns with RPGs as games of a particular type. Perhaps this is because I’ve only played later Breath of Fire iterations, and had little in the way of preconceived ideas about the series, but these chapters spoke to experiences I’ve had from a direction I wasn’t expecting, and landed with startling insight. Maybe this is how people who haven’t played Xenogears would feel listening to my interminable podcast commentary on that game; one can hope! I love the idea that within an objectively slightly janky game, “you may be able to spy the inner workings of a mythos in the making” (168). I would even go further and say that not despite but because of the obstacles in the way of such a glimpse of the seed of a mighty idea, old games like Breath of Fire are inseparably fused to this homeless time of ours, when we deal daily with such a dearth of living myths that we will grab onto them anywhere we can. The games’ religious ambiguity and political, race- and class-conflict story beats, in this light, are almost too poignantly prophetic of our current confusions and divisions. And they shed a light, a warmth, a breath, why not, over players who take the time, as Norton does, to connect deeply with their stories and weave them into their own. Witness some snippets:

Upon starting a new game… a voice in the darkness cries about giving yourself to God and becoming God’s strength…

This is none other than Breath of Fire II, the globe-trotting, history-spanning, darkly religious, draconically epic sequel to the original Breath of Fire, though I describe it simply as “formative”… I spend a lot of words in this book regarding themes, analyses and the meaning embedded in these stories told by means of the Super Nintendo, but when it comes to this game… it’s personal.

Breath of Fire II immediately won my heart from the moment I saw its beautifully realised world, a crystallisation of all of Capcom’s 16-bit sensibilities…

What I didn’t realise at the time was the fact that this game would not only win my heart, but also my soul. I know; even to me it still seems odd to describe encountering a video game, a mere sequel, as a religious experience. Yet somehow, I’ve wasted years describing the early Breath of Fire games as staunchly traditional. I’d like to recant…. (177-179, excerpts; British spellings courtesy of Bitmap.)

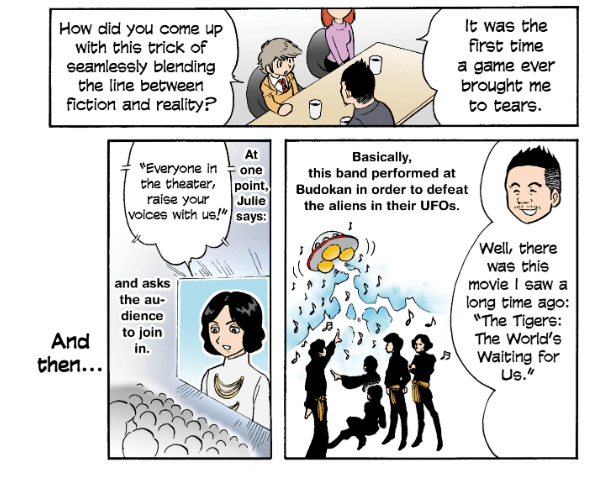

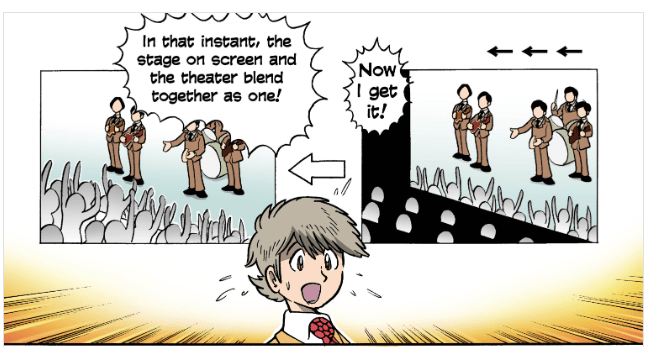

Over the course of a nuanced discussion of the game’s religious themes, centered on the duplicitous Church of St Eva, tied in with personal reflections about growing up “in the church” of Western missionaries looking at “the monarch chrysalis hanging from a branch outside” as an image of Pauline transformation (yep, that Paul), an image of the winged anime girl Nina above a cartouche of text discussing a goddess joining the player’s party is balanced against a lengthy passage from CS Lewis on “the Numinous” (182-3)–and lo, it hit me like the thunderbolt on Ryu’s sword that the construction of Norton’s book, heartfelt, syncretic, overflowing with connections between games, literature, and life, mirrored almost exactly the message of these games which he sought to express. The content and form, medium and message, like a successful dragon transformation, were one. And to cap it off, on the next page Ryu celebrates catching a fish as Norton explicates what I had perceived: “It was in this realm of fusion and confusion [Hawaii both as place and as touchstone for his studies of myth and religion] that the roots of my interest in spirituality dug deep, and I really have Breath of Fire II to thank for that” (185).

Again, I found the book immensely valuable precisely because it taught me so much about games I only knew the name of, if that, and will likely never play. Thankfully, Norton has trekked through the likes of Brain Lord and Inindo so I don’t have to, and recorded his discoveries. In a few cases, I also may go ahead and track down some of these more obscure titles just out of curiosity, or to show them to my students or my own kids out of a kind of historical whimsy. But I will undoubtedly move the Breath of Fire series right onto the mental shelf with EarthBound and FFII and find time to play them alongside one another someday.

Norton’s chapters each close with brief notes from other players corroborating and qualifying his reasoning, layering onto his experience of the games the texture of their own voices and memories. Of Breath of Fire, Livnat writes “I also loved that fact that for me, who was also just learning English, there was no real need for a lot of dialogue to get the picture; in fact it enabled me to fill the void of plot with my own understanding of the game, and my own ideas and thoughts” (173). This is much the way Toby Fox talks about learning to read from EarthBound, and how I remember learning from JRPGs like Dragon Quest and FFII my own language, reflected back to me across the bridge of terse NES and SNES localizations; or later, learning Spanish from Platero y yo, before I knew most of the vocabulary enchanted with its sound; or how Philip Pullman talks about the prose of Kipling’s Just So Stories, or the poetry of The Journey of the Magi and Paradise Lost. To repeat, these old games, like these great books, encode a universal archetype, that of the learner–of language, or myth, or a game’s rules–facing a mystery and patiently listening, imagining, playing their way towards comprehension.

It bears mentioning once more that the visual style of Norton’s book, too, is almost intoxicatingly good. The layout, the choice of sprites, backgrounds, and other assets, and still more the peculiar CRT-filter quality of the images, all argue as strongly as the words about the need for us a culture to continue re-evaluating the role of nostalgia and the place of games in the artistic canon.

All this is not to say the book is perfect. A line of text from Daniel Greenberg’s testimonial about Mystic Quest gets transposed 20 pages ahead to the top of Mama Terra’s for FFIII (421). Accompanying Norton’s text and his contributors’, exemplary screenshots from the games, many of which he played through while streaming on Twitch, and pull-quotes from developers and players alike carry the reader along. But as befits a book like this, not meant to be caparisoned in scholarly apparatus, these are not specifically cited.

Consider this passage from Yuji Horii: “The most important part of a RPG is the player feeling like they are taking the role of a character in a fully realised fantasy world. They can explore, visit various towns and places, talk to people, customise their character, collect various items, and defeat monsters. The story is not the focus of the experience and is only there to make the atmosphere of the fantasy world more interesting and engaging during the course of the game” (47).

Where did this quote come from? On the one hand, I can see the problem other armchair academics/neckbeard Karens might have with not knowing for sure, not knowing if Norton has done his homework and cited his sources properly. I, for my part, love that I can cite Norton’s book the next time I attempt to elucidate or take to task Horii-san for this seemingly apocryphal quote. It doesn’t matter so much where or even whether he said it, because he’ll a) never know I am writing about him, and b) if somehow my work were to come to his attention, he’d in all likelihood be perfectly secure in his stature as the godfather of the genre, caring not a whit for what I might quibble with in a quote attributed to him by, among many others, fellow scholar-fan-content-creator Moses Norton.

To be Frankystein Mark II, I have not nearly so much to say about A Guide to JRPGs by Kalata et al., but I definitely wanted to note its presence in this connection. When I went to buy The Definitive Book from Bitmap, I couldn’t pass up the appeal of A Guide to JRPGs. It’s not that I don’t find the book as interesting or readable as Norton’s (though I don’t mind saying that I don’t); it’s a very different beast, and not as much to my personal taste. Almost devoid of the personal touches and wrestling with deep questions, both of meaning and mechanics, that characterizes Norton’s work, Kalata’s instead aims for breadth of inclusion rather than depth of inquiry. So I allude to it here mostly as a point of reference.

Now, there are definite strengths to A Guide’s approach, and enormous quantities of information to be found there much more pleasantly than by trying to search for it on wikis with the help of google translate. The very unassumingness of its title, A Guide, belies the wealth of arcana in store for the reader. Even I, I’ll confess, have not managed to read this one cover to cover, though I made sure to dip into favorite games, obscure artifacts of the pre-Famicom era, and salient introductory sections like “What is a JRPG?” “A History of RPGs in Japan,” and “Attack and Dethrone God.” For anyone interested in topics like these–that is to say, just about anyone still reading this, AIs excepted–A Guide is a treasure trove. The perfect combination of bedside curio and coffee table conversation piece, its 650-odd pages and painterly cover adorned with a red binding somehow contrive to feel almost weightless. The prose, similarly, though it lacks Norton’s spiky charm and consistency of voice, being written by a large crew of expert contributors, is nevertheless light in tone, more journalistic than essayistic, and manages to remain easily readable despite the necessarily tiny font.

For a more Norton-esque entry in the same encyclopedic vein, see also Aidan Moher’s Fight, Magic, Items (and my review here) or the Boss Fight Books collection (ditto), though those are each about a single book, for the most part, and would have to be grouped together, Power-Ranger-like, to contend on something like the same scale. But do yourself and your RPG-loving loved ones a favor: the holidays are close enough, surely, to warrant a gift, even if it’s a bit pricey. Books like Norton’s and Kalata’s promise, in turn, the gift of conversations, debates, playthroughs and shared memories. To be passionate about old games is all well and good, but these debates are best conducted cordially, just as the books about them will be most profitable if read charitably. If the conversation that is our shared culture is to be sustained at all, we have to carry it on remembering that there is a person on the other side of the screen, someone who’s fortunate to have been bathed in the same sort of CRT glow we remember, maybe, from the sun of a winter’s or summer’s holiday long ago.

Please, read the books for yourselves and comment responsibly.