So as to establish some sort of structure by which to embrace the world in all its complexity and learn about it as deeply as possible through the mediation of a shared, relatively safe and replicable experience, for a long time now we’ve been leaning on this lens of play and games here at The Video Game Academy. And yet it cannot have escaped anyone’s notice who might be following along that what we are up to is rather different from, say, the dream of “gamification” in education that various figures of wide-ranging levels of influence might talk about, or even “game studies” in any strictly defined sense. In fact, our courses, such as they are, are remarkably old-fashioned in many ways. Essentially, we play games and talk about them; or we take a larger theme, such as “mythology,” this year’s focus, and explore it through games and other recommended readings.

In the spirit of Pullman’s advice to “read like a butterfly, write like a bee,” we remain open-minded about the selection of readings that would ultimately find inclusion in our course of study. And because all this remains speculative and hobby-horsical, we don’t have to limit ourselves to fixed curricula and syllabi, as interesting as it is to think about these things from time to time (see recent episodes of “Unboxing” and our own Professor Kozlowski for reflections on some of the work that goes into professional academia).

But in the words of Buzz-Buzz, “a bee I am… not.” Much as I strive to keep up with the writing that is meant to accompany and give expression to all this reading (reading in the loose sense of listening and playing and so on), I find that weeks and months go by with little to show for all the ideas I intend to share out again. The occasional post, to say nothing of new courses or published pieces, is only with great effort and continual procrastination ever finished (again, in the loosest possible sense of the word). Still, as another artistic hero said to yet another, “work, always work” (Rodin to Rilke): the work is ongoing, the reading is happening, the notes are jotting, and thoughts thinking. If nothing else, a conversation on FFVIII is forthcoming more or less weekly.

Is it at least somewhat convincing to plead that I’m waiting for Pullman’s new book to release before diving into that podcast project again? Or that I’m collaborating again with Moses aka Red on a follow-up to his Gamelogica project, though what form that might take remains to be decided? Perhaps I’ll talk about the Nobel winners I’ve been reading, or attempt a playthrough of MOTHER 2 in Japanese…

Meanwhile, in brief reviews and commentaries, I’ll keep tracking the connections between games and literature as best I can. From my attempt at putting The Sirens’ Call by Chris Hayes into dialogue with Deep Work by Cal Newport and Saving Time and How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell, I arrived at the conclusion that for all their insights into the critical importance of attention, these contemporary authors seem to me to be completely missing the point. Instead of writing these popular sorts of books, long on citations and case studies and strikingly short on the deep reading they purportedly are calling for, they should have done better to craft a single reflection on the example that was most exemplary in each case. Lacking any demonstrable rootedness in their points of departure–whether Homer and Plato for Hayes, Jung and Montaigne for Newport, or Bergson and Benjamin for Odell–to say nothing of any perceptible religious or otherwise philosophical groundwork for their arguments, their books diffuse themselves into the culture as distractedly as any other media phenomenon, and will likely prove as ephemeral. And so I suggest readers turn instead to those sources in literature from which they are drawing, and abide in the original works for themselves. For a better guide as to how to do this, I could lift up Weil on the use of school studies; Bakhtin on Dostoevsky; and someday, perhaps, my own efforts on video games.

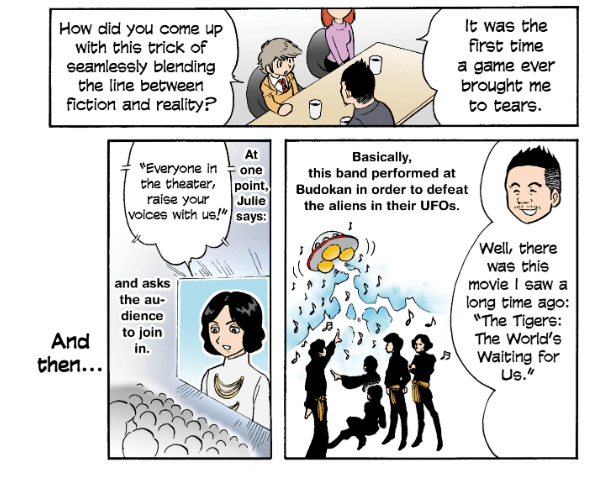

To connect this all to video games, then, can we do better than Jenny Odell’s reasoning behind her structuring of Saving Time? As she explains in this BOMB interview:

… I actually didn’t have the idea to structure the book that way until halfway through writing it. I landed on the idea because I was playing the video game, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. I was spending a lot of time in a spatially dispersed story in which you understand that certain things can only happen in certain places, and you have some idea of something that’s coming both narratively and geographically down the road. You can see it, it’s in the distance.

At the time, I was thinking about how everyone’s experience of playing that game—even though it obviously suggests some routes to you—is pretty different, and thus, their memory of the story is going to be different. I was just really fascinated by that. So I think it made me look twice at these places that I was spending time in and it got me thinking about how I could string them together.

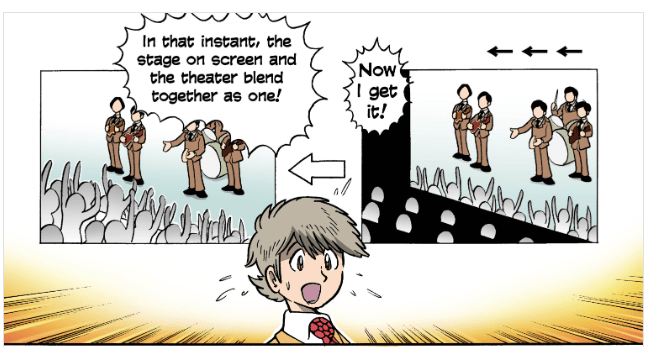

Odell is extremely close here to digging into the power of place for memory as represented in video games writ large. While she focuses on the differences among players, my mind goes as usual to EarthBound, and to the ultimately unified story it tells. No matter in what order the sanctuaries are visited, or in the case of Zelda, the memory locations, Koroks, shrines, etc., there are certain themes, timeless and universal, such as love, courage, and the joy of adventure, which these games will reliably lead players to consider.

It almost makes me want to go back and read her book again in light of this revelation!

In passing, I’ll note that Hayes and Newport each do make a few interesting references to video games, too. Apropos of Socrates’ critique of writing in the Phaedrus, Hayes remarks, “It seems safe to say in hindsight that writing was a pretty big net positive for human development, even if one of the greatest thinkers of all-time worried about it the same way contemporaries fret over video games” (6). And he later acquaints the reader with Addiction by Design, by Natasha Dow Schull, and the prevalence of loot boxes via this inarguable clickbait from The Washington Post: “Humankind Has Now Spent More Time Playing Call of Duty Than It Has Existed on Earth” (52-3).

Besides becoming bywords for the perennial moral panics accruing to new technologies and for the irresistibility of slot-machine-style addiction, video games, again exemplified in Call of Duty, return one more time towards the end of the book to provide Hayes with fodder for a brief rant: “Online interaction, which is where a growing share (for some the majority) of our human interactions now takes place, becomes, then, almost like a video game version of conversation, a gamified experience of inputs and outputs, so thoroughly mediated and divorced from the full breathing laughing suffering reality of other humans that dunking on someone or insulting someone online feels roughly similar to shooting up a bunch of guys in Call of Duty” (233-4).

A different paradigm shows up in Newport: “In MIT lore, it’s generally believed that this haphazard combination of different disciplines, thrown together in a large reconfigurable building, led to chance encounters and a spirit of inventiveness that generated breakthroughs at a fast pace, innovating topics as diverse as Chomsky grammars, Loran navigational radars, and video games, all within the same productive postwar decades” (129). The absence of a descriptor there, or if you like, the way in which “video” is returned to the role of descriptor of “games” according to the parallelism of Newport’s construction, is extremely interesting. I could gripe all day about the narrowness and specificity of the video games Hayes seems to have in mind; whereas for Newport, video games are a product almost without qualities other than their novelty and mythic origin in “MIT lore” and “haphazard…inventiveness.” Whatever he may think about particular games, Newport’s mention of them at least has a positive valence.

By chance, the one episode of Newport’s podcast that I listened to so far (no. 288, on the recommendation of this article I was considering assigning next school year) includes towards the very end some reflections on Tolkien which might finally get me to segue back to the ostensible premise of this post. Specifically, a curator of medieval manuscripts at one of the libraries of Oxford sent Newport a quote that is found in a letter from Tolkien to Stanley Unwin: “Writing stories in prose or verse has been stolen, often guiltily, from time already mortgaged…”

Before addressing–or indeed quoting–the quote, Newport riffs on “The Consolations of Fantasy” exhibit (reviewed here) and pulls up some of the art for his youtube viewers. He read in a recent biography about Tolkien “being overwhelmed by…the stresses of being in a field–philology–transforming into modern linguistics,” noting that “he was on the old-fashioned side of that.” Repeatedly, he characterizes Tolkien’s art and writing as abounding in “almost childlike, fantastical images” and takes his desire to spend more time in the “fantastical worlds” of his “childlike,” albeit “sophisticated,” imagination, as another explanation of his acute sense of stress–along with his worries about money.

Newport may or may not have ever read Tolkien–it isn’t clear–but he sees his art anyhow as being illustrative of his own recent work on “Slow Productivity.” He argues that Tolkien’s success selling books is what allowed him to spend more time on his writing and worldbuilding and to worry less about his other responsibilities; again, though, Newport seems to completely miss the point. What is it about Tolkien’s books that so captivates readers? It has less to do with a yearning for time in which to daydream and more to do with his insights about myth, drawn straight from his studies of philology and given voice in a much more famous quote from Gandalf: “All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.” In his fiction, both in major works like Lord of the Rings and in small masterpieces like “Leaf By Niggle,” as well as his scholarship (talks on Beowulf and Fairy-stories are essential) Tolkien touches on just those emphatically moral dimensions so absent from Newport’s pursuit of excellence.

Now reading widely and breezily in the literature of attention is as fine a way as any to pass the summertime for a none-too-disciplined teacher like me. But make no mistake: setting aside my personal affection for Pullman, not entirely shared by my colleagues, I should clarify that second to none among our professorial and scholarly lodestars, we at VGA also count JRR Tolkien and CS Lewis. Both were eminent in their fields of language and literature, and both were theorist-practitioners of the arts of teaching and of fiction alike. And their work is at the heart of the 20C turn to myth-making which continues most vivaciously in the video game medium to the present day, and which is particularly evident in the 90’s JRPGs we never tire of playing and studying.

If it may be objected, quite fairly, that discussions of classic game series like Final Fantasy and The Legend of Zelda have been done ad nauseum, whether as podcasts, video essays, or even books, so what do we mean by proposing continually to return to them anew; much more so discussions of Tolkien and Lewis, who are the subjects of innumerable books, articles, videos, podcasts, and courses? Even a cursory glance at the literature suggests that the influence of Tolkien, Lewis, and their circle and successors on video game development and reception has been immense, as is well understood. From the very first PhD dissertation on video games by Buckles to more recent work aimed at scholars (Young), hobbyists and serious fans (Peterson), and a popular audience alike (Kohler), it is clear we would be far from surprising anyone with our discoveries about the deep ties between the seemingly dusty “Lang and Lit” debates of the early 20C and the “ludology/narratology” tug of war or “magic circle” duck duck goose of near-contemporary game studies.

To my (admittedly very incomplete) knowledge, however, what remains little noted or discussed is the role of play within the work of the Inklings and Inkling-adjacent, their predecessors (ie. Chesterton and Morris), and their major intellectual heirs (whether imitators, who are legion, or virtual parricides, in Pullman’s case). What happens when we go back to their writing the hindsight afforded by reading them in the light of video games’ subsequent developments of the themes of mythopoesis so powerfully instaurated by the dynamic give-and-take between Tolkien, Lewis, and their fellows and followers?

To illustrate just a few potential starting points:

Tolkien’s thoughts on “faerian drama” in the light of video games (Makai); the impression made on him by the play Peter Pan in his early Cottage of Lost Play writings (Fimi); games as mythopoeic narratives (Fox-Lenz) and the riddle game at the heart of The Hobbit (Olsen).

Lewis’s language of “checkmate” and “poker” to describe his conversion (Dickieson), and the ways in which imagery of play and games functions elsewhere in his apologetic writings, fiction, and scholarship:

- “Very often the only way to get a quality in reality is to start behaving as if you had it already. That is why children’s games are so important. They are always pretending to be grown-ups—playing soldiers, playing shop. But all the time, they are hardening their muscles and sharpening their wits so that the pretense of being grown-up helps them grow up in earnest (Mere Christianity)

- The discovery, creation, and defense of Narnia are all couched in terms of play, ie. “I’m going to stand by the play world” (The Silver Chair); and for some reason “The Great Dance” at the end of Perelandra is also called “The Great Game”

- In his analogy of Milton asking “What kind of poem do I want to make?” with “a boy debating whether to play hockey or football,” Lewis likens the game rules to the poetic form (Preface to Paradise Lost)

To my mind, there is ample material here for a course and a curriculum. But as I say, this summer I’m spoken for, reading in the backlists of the Nobel Prize laureates from a century and more. But keep an eye out for the follow-up to Moses’ Gamelogica channel, tentatively to be known as Legendaria!