In Fight, Magic, Items: The History of Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, and the Rise of Japanese RPGs in the West, Aidan Moher delivers on the promise of an idea or idle dream many of us have shared but all too few have realized: recounting the stories of the games we love and weaving those stories together into the tale of a genre, a medium, and an industry over the course of a book.

Reviews abound, as the book has been out for a couple of years–mostly positive, from what I can tell, and for all my sour grapes I can’t disagree: the book itself is even out there in audio, so I highly recommend checking it out. While the definitive book on JRPGs, if there is such a thing, remains to be written–and while the writing of such an ideal book, even if quixotic, seems well worth the effort–having this bird of Moher’s in hand makes for encouragement, inspiration, and provocation.

As the book goes on, tracing the development of the genre chronologically, I personally grew less and less interested, even as (or perhaps because) the games under discussion were more new to me. Having set up the basic structure of the history of JRPGs as a kind of dialogue or dialectic between the Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy series, Moher slips into reportage rather than analysis for the bulk of the text. Still, there are a number of insights and simple points of fact that make the text perfectly adequate for what it is setting out to do. Appealing to a broad audience, Moher gives enough context for the general reader, as well as peppering his chapters with insights for those who are more familiar with the basic outline. Along with the many iterations and generations of the core series DQ and FF, he does fit in a range of lesser-known games and series into the narrative.

While convincingly making the case for the coherence of his subject, Moher also includes just enough of his own subjective experience to hint at the importance of this history for the individual. Plenty of background information is given for anyone in the audience who hasn’t lived through it, and those of us who would have liked to write such a book are spared the effort of a certain amount of historical research, while the work of introspection and deeper analysis remains. Given the scope of his work, Moher necessarily touches lightly on any given game. At times, even beloved and important games appear only in the form of inset thumbnail sketches, or in a stray reference. Just as the history of JRPGs is ongoing, so he acknowledges that his own research is only offering one viewpoint among many–including his own future writing, podcasting, and so on.

For another look at JRPGs, on the recommendation of sometime interlocutor and friend of the site Dylan Holmes–whose book A Mind Forever Forever Voyaging does touch on the genre as well–pay a visit to the Digital Antiquarian, where JPGs are placed within the much larger framework of CRPGs as a whole.

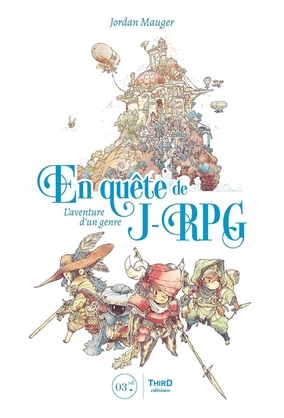

For more on those two other proverbial birds, and without too much beating around the bush, I heard that a certain gamelogician is working on a book on RPGs, which I’ve been looking forward to. Or was it a oiseau that told me? If you happen to read French, consider the approach taken by Jordan Mauger. En quête de J-RPG: L’aventure d’un genre has yet to be translated into English. The title might be translated In Search of J-RPG, as The Video Game Library has it, but it also puns on enquête, a word whose range of meanings includes “investigation, survey, inquiry” as well as the root meaning of “quest”. Like so many of us, Mauger is simultaneously making the case for the importance of his subject while also treating it as important and worthy of detailed analysis. My own French is far from adequate to understanding all the nuance of his argument and his numerous puns and plays on words, but insofar as I could read it, I definitely enjoyed and would recommend this book, as well.

In short–and again, I apologize for the brevity and slovenliness of these posts lately–anyone out there writing about games like these, like this, take heart! It can be done, and it is. And it can always be done better.