It’s 1997, and Squaresoft just released a game that many have called the greatest video game of all time.

I’m not here to defend or dispute that claim. In fact, I’m not here to talk about Final Fantasy VII at all (or at least beyond using it to contextualize our discussion). I think there’s plenty of folks talking about FFVII already—including the team developing a series of contemporary games that are part-remake, part-commentary on the original text of Square’s masterpiece.

I want to talk about the aftermath. The gawky, imperfect sequels of the same console generation that have never received as much love, attention, or admiration, despite their own complicated legacies. I want to talk about two games that will likely never get full-fledged re-makes, because their popularity falls well within the shadow of that first 3D Final Fantasy game. Not just because I like championing lost causes (though I do), or because I’m not-so-secretly a bigger fan of Final Fantasy VIII than VII (though I am), or because I just got through beating Final Fantasy IX for the first time ever (though I did), but because I think there’s a fascinating dynamic at play between these two games that warrants investigation. In many ways, these games are more polished than Final Fantasy’s breakout Playstation RPG, yet are not as well liked. And in an age where many a game withers on the vine for lack of polish, that’s a phenomenon worth examining.

What’s more, I think these games reflect an interesting moment in the legacy of this franchise. And now that we’re up to the sixteenth numbered entry in the series, never mind the spinoffs (like Tactics), expansions (looking at you, XIV), and internal sequels (wtf, XIII?), re-examining this moment in that legacy can tell us a whole lot about how we got to this point, both in terms of what fans expect from a Final Fantasy game, and what developers feel obligated to bring to the table.

But naturally, we have a lot of stage-setting to do before we can talk about these two games and the legacy they belong to. So, as the song says: Let’s start at the very beginning…

Setting the Stage

Or, actually, let’s not. Beginnings are for suckers, and are especially inappropriate when talking about this particular franchise.

See, my first Final Fantasy game was Final Fantasy VIII.

I did not own an NES or SNES, but sprang into my video game career with the N64. I was probably around eleven or twelve at the time, and it was a kid-friendly purchase full of kid-friendly games that I could play with other kids my age and younger. There were a few adult-oriented games that crossed my path (Goldeneye 64 being the standout example), but the vast majority of the games in our household had Mario, Zelda, Pokemon, Star Wars, or Banjo-Kazooie pictured prominently on the cartridge.

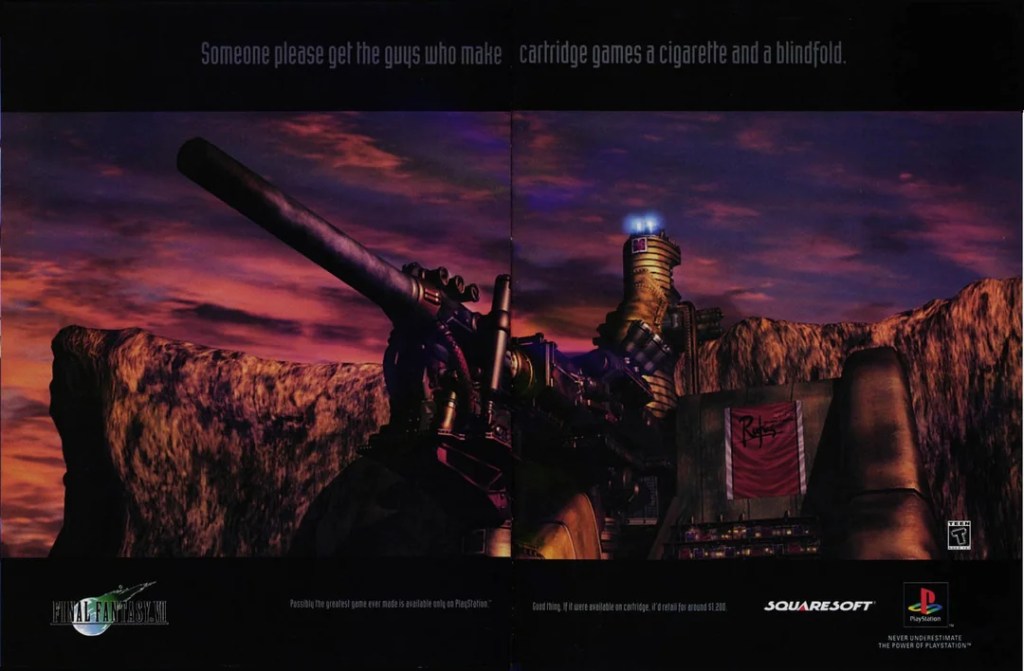

But eleven and twelve are delicate ages, giving way quickly to thirteen, which is a whole ‘nother business entirely. Thirteen-year-olds are very self-conscious about their own immaturity, and are suspicious of anything “kiddie” that is pandered to them. So I was squarely in the crosshairs of an aggressive marketing campaign designed to paint the Playstation as the “grownup” console, with serious games for grownup people, as opposed to the “kiddie” N64.

This was not a new maneuver. Sega had made the exact same play some five years ago when they promoted Sonic as the “cool alternative” to Mario. But games were maturing as an art form, and the N64 had made the controversial choice to continue favoring cartridge games over the hot new CD’s, which had brought about an even deeper rift than usual between the two consoles.

See, CD’s could store a lot more information, but you could not write to them. So Playstation required you to buy memory cards (cartridges) for your savegames (alienating children), but could also promise significantly larger and longer games, especially since you could make a game with multiple CD’s saved across a single, constant memory card.

And Square, always pushing the boundaries of their medium’s ability to tell stories, had jumped the Nintendo ship in favor of Playstation’s CDs: where they could continue to tell their 30+ hour stories, despite settling for inferior processing power.

So while Sonic and Mario were just two flavors of the same mascot-platformer (though Sonic did showcase the Genesis’ superior processing power), in 1997 there was a clear demarcation between the N64 and the Playstation: the N64 could promise fun mechanically-intensive games beyond what the Playstation could feasibly render, but the Playstation could offer deep, multi-disc games that told involved, engaging stories. And it was not hard to spin this as “kid-games” vs. “adult-games”.

So when thirteen-year-old me went to my Playstation-owning friend’s house (we’ll call him J for convenience), I was very conscious of a kind of maturity divide. J promised me a more adult experience: serious, mature games (rated T for TEEN!) with the closest thing video games had to sex icons (Lara Croft! Aeris and Tifa! Topless anime girls!). And while I wasn’t terribly interested in most of this, I was still curious about what the Playstation had to offer, and what a “grownup” game actually looked like. And, of course, J was a passionate apologist of the Final Fantasy games, and I was eager to see what all the fuss was about.

So one day we were looking at his game library and he asked me which one I wanted to play, and there was a very obvious problem.

Final Fantasy I was not an option.

Numbers

I don’t think it’s weird to want to start at the beginning. But in the late ‘90s, playing all the Final Fantasy games in order really wasn’t something you could do in the states.

Let’s recap real fast.

Final Fantasy (I) – released on NES in Japan in 1987

- released in USA in 1990

Final Fantasy II – released on NES in Japan in 1988

- first released in the USA (with FFI) as “Final Fantasy Origins” for PS1 in 2003

- re-released in USA (with FFI) as “Final Fantasy I & II: Dawn of Souls” for GBA in 2004

Final Fantasy III – released on NES in Japan in 1990

- first released in USA as a DS re-make in 2006(!)

Final Fantasy IV – released on SNES in Japan in 1991;

- released in USA as Final Fantasy II (!?) in 1991

- re-released (with Chrono Trigger) in USA as “Final Fantasy Chronicles” for PS1 in 2001

Final Fantasy V – released on SNES in Japan in 1992

- first released in USA (with FFVI) as “Final Fantasy Anthology” for PS1 in 1999

Final Fantasy VI – released on SNES in Japan in 1994

- released in USA as Final Fantasy III (…) in 1994

Don’t even get me started on the releases in Europe and Australia.

So all that to say: there was no such thing as “canon” in Final Fantasy at this point. And when I looked at J and asked (reasonably, I thought), “where’s the first one”, he told me it didn’t matter where I started, since the games didn’t have continuity anyway.

Given this new information, I decided to start as early as I could get: Let’s play Final Fantasy VII.

And I have no idea why, but J never knew where the first disc of Final Fantasy VII was. I swear he told me this was his favorite game a zillion times, but I have no evidence that he ever played it.

So, naturally, I asked to play Final Fantasy VIII instead.

Something like four or five times, this happened. I played the first hour or two of Final Fantasy VIII at a friend’s house four or five times. And as early as the second, J asked:

“Why doesn’t anybody like Final Fantasy IX?”

So, basically, from my earliest introduction to the series, I’ve always had a sense that there is some kind of internal rivalry between Final Fantasy VIII and Final Fantasy IX. It’s dumb, but there it is. And it’s as good a place to start an essay as any, I guess.

But Seriously, I did play them all that one time

In 2008, the summer after I graduated from college, I decided to do this for realz.

At this point, I’d bought a PS1 (and PS2), owned every Final Fantasy between I and X, on something like four different consoles, and I decided I was going to systematically play through the series.

So I did.

It was not a perfect playthrough, I should mention. I did not beat the final boss of Final Fantasy II (turns out, if you miss one particular item, you’re basically screwed in the final battle), and I did not actually beat Final Fantasy IX. (Cut me some slack; I’d just played EIGHT games. This is, however, something of a trend—as we’ll discuss.)

Here are some basic observations about the franchise, based on that play-through:

1. In the first six games, the odd-numbered ones (I, III, V) have more archetypal stories and characters, and use a job system to let the player customize the characters; while the even-numbered ones (II, IV, VI) use much more vividly-drawn characters in complex plots, though they do not offer the flexibility of changing your characters’ skills, stats, or jobs beyond their inventory.

2. Final Fantasy VII and VIII fuse these two halves of the franchise: they both have robust character-customization systems for managing combat, while telling engaging stories with distinct characters. VII clearly borrows from the VI mold by giving you multiple optional characters you could recruit (or miss), while VIII favors the I/III/V habit of a fixed, small cast, though they are more richly developed than would be typical of those games.

3. Final Fantasy VII and VIII also continue the franchise’s tradition of gradually moving forward in time. Where I is a clear-cut medieval fantasy, IV, V, and VI had more of a steampunk, industrial-age aesthetic to them. VII spends a lot of screentime depicting the urban decay of Midgar, which runs much closer to modern urban fantasy, and while VIII’s moment in time is very ambiguous, changing over the course of its run-time, it most often feels like the world has reached a level of technological progress comparable to our own (at least in 1999).

4. And, obviously, the move to 3D for VII, VIII, and IX is a huge gamechanger for the franchise. These games are much more accessible, much more immediately arresting, and easier to obtain to boot. This may not be so true in 2024, when everything can be digitally distributed, and Square Enix can market the whole series as a bundle, but I imagine that fans of Final Fantasy XIV and XVI still don’t feel much compulsion to dig into the back catalog beyond VII. I could be wrong, and I know my Gen-Z students occasionally dig up obscure games from the ‘80s and ‘90s I’ve never played, but I imagine that would require substantial dedication—even more than in 2008.

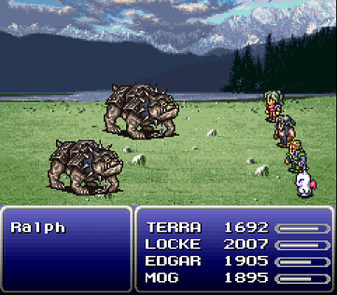

5. Final Fantasy IX is a clear throwback to the earliest origins of the franchise, in aesthetic, setting, and by offering fewer character customization options. It is very much the answer to: but what if we just did Final Fantasy I or III with modern hardware capabilities?

2008’s rough ranking, from best to worst: VI, VIII, VII, IV, IX, II, V, I, III.

(I’m not sure why it was important to share that, but it seemed very important at the time for me to have played all these games and come up with a definitive ranking of each. Anyway, if you’ve got a problem with those standings, take it up with 2008 me.)

The Western JRPG

There’s one more thing we have to talk about before we deeply dive into 1997 and beyond:

What makes Final Fantasy—the whole franchise—special? Why did 2008 me feel compelled to play all these dang games? Why was this the definitive JRPG in 2008? Why is its legacy significant enough to warrant an essay in 2024?

This is a tricky question.

At least part of the reason that above release schedule is so ding-dang complicated is that Square and Nintendo didn’t have much faith in the success of JRPGs in North America. Dragon Quest (I) got a pretty respectable North American release in 1989 as Dragon Warrior, which is probably why the first Final Fantasy game also got localized the next year. But where Final Fantasy took off in the states, Dragon Quest languished, despite being the more popular series in Japan.

Critics and commentators usually point to the superior graphics, music, and mechanics of Final Fantasy for capturing the attention of Western audiences, and that’s something that should give us pause. Because even if that explains the popularity of Final Fantasy in the states, what it doesn’t explain is why Dragon Quest remained more popular in Japan. Both are JRPGs. Both derive from the same storied Western-medieval-fantasy lineage of Dungeons and Dragons as re-interpreted by Japanese game developers.

Kurt Kalata at GamaSutra pointed out in 2008 that part of Dragon Quest’s appeal in Japan (and disfavor in the states) derives from its adherence to tradition:

Throughout its life, Final Fantasy constantly reinvented itself, keeping certain aspects but bucking trends with each iteration. On the other hand, Dragon Quest has been strongly about keeping with tradition. All of them take place in the same European-style medieval world. All of them feature the same key staff members — Horii, Toriyama, and Sugiyama. As a result, the method of storytelling, the characters, the battle system and the style of music is pretty much the same throughout. It’s a series that prides itself not only on familiarity and nostalgia, but also in its consistency.

Final Fantasy is not consistent. As J told me in 2001, there is no continuity among Final Fantasy games. At the time, he told me each game was set 100 years after the last one; I’m not sure if that’s canon, but I can tell you for sure that no two Final Fantasy worlds look alike, and callbacks to previous games are rare (at least until FFIX). The mechanics shift or innovate regularly; each entry represents a substantial graphics upgrade on the last; the cast entirely changes with each game (with the exception of somebody showing up named Cid, and some few other outliers like Cloud’s cameo in Tactics).

And, I should stress, Final Fantasy has always been about spectacle. It’s easy to point to the fancy CG’d cutscenes of VII, VIII, and IX—and even easier to point to the hyperkinetic action scenes of modern entries like XIV and XVI—but even as far back as the first few entries, spell effects and summons and monsters were meant to be dramatic, fierce, and eye-catching. The stories are epic and melodramatic, with arch characters and cataclysmic stakes, if only to better set up these big, memorable story beats.

It’s easy to point to Dragon Quest as Japan’s JRPG, and Final Fantasy as the “Western” JRPG, but it’s worth pointing out that this is not a matter of cultural content. Both are “western” in the sense of dealing with knights, kings, and European-style castles, rather than samurai, emperors, and Himeji-style fortresses. It’s true that Final Fantasy features a grab bag of western references atypical to Dragon Quest, but those references are hardly curated with a North American audience in mind. You can point to Odin and Excalibur in a Final Fantasy game as frequently as you can point to Rama and Masamune, never mind the regular appearance of Bahamut. But I think it’s the two pillars of spectacle and innovation that really drew Western audiences into the franchise.

Back to 1997

I stress this, because if Final Fantasy VII did anything right, it was spectacle and innovation. I know we academics and commentators like to dig deep into the story and give it a deep read into themes and psychology, but let’s be real here.

Final Fantasy VII looked damn cool.

In 1997, there wasn’t anything like it. It was flashy and colorful, filled with these broad characters, arch moments of drama (like Aeris’ death) punctuated by Uematsu’s bombastic, heartfelt soundtrack, summons and spells that lit up the whole screen with full minutes of particle effects, dramatic poses, and wild (to the point of absurdity) demonstrations of power.

Yes, this was the “grownup” alternative to the gameplay of something like Ocarina of Time or Mario 64, but we are absolutely kidding ourselves if we think this was “mature”. The immediate appeal of Final Fantasy VII was every bit as silly and juvenile as the immediate appeal of something like the Matrix, two years later. But it was framed as adolescent appeal: teenage boy power fantasies of shredding your enemies with Omnislash instead of “kiddie” fantasies of gleefully flying through the air unimpeded with Mario’s winged hat or Kazooie’s red feathers.

And it felt adult. N64 games did not give you the kind of pathos you felt when Aeris died, or the complex psychological exploration of Cloud’s dream sequences, or the dark, science-fiction plot of genetic experimentation and nations warring with one another. There was a kind of substance here you could not find in other video games of the time, it seemed, even under the explosions and cutscenes and power fantasies—especially fresh if you were a kid with a console, and not playing the Western RPGs and early shooters on late ‘90s PCs.

But like I said at the beginning of this essay: I don’t actually want to talk about Final Fantasy VII. It casts a long enough shadow already. This is supposed to be about legacy.

And the legacy of Final Fantasy VII is big and complicated.

Final Fantasy VII was the first JRPG to become not just popular, but a full-scale cultural phenomenon in the West. As in, the one-two punch of Final Fantasy VII and Toonami on Cartoon Network (also in 1997!) was almost certainly the tipping point for the wide popularization of Japanese culture in America, full stop—certainly among my generation.

Final Fantasy VII was the flagship game for an entire approach to video gaming: as strong an argument for “games as art” as existed at that time (remember: Ocarina of Time did not release until 1998).

And, consequently, Final Fantasy VII became the primary reference point for Western audiences to understand and interpret Japanese video games in general, and JRPGs in particular (if not Japanese culture altogether). Whatever games followed: Legend of Dragoon, Chrono Cross, not to mention the Final Fantasy sequels—these games would inevitably be compared to Final Fantasy VII; and, likewise, it almost certainly enabled all those re-releases of old Final Fantasy games we listed earlier.

So, Squaresoft—how you going to follow that one up?

That Beautiful Mess

I love Final Fantasy VIII.

I mean, I’m pretty sure I could just end the essay there and feel pretty comfortable that I’ve expressed most of what I wanted to say in sitting down to write this in the first place. But, seriously. I love Final Fantasy VIII.

And this is not something I feel like I can admit without qualification. Teenage, early-2000s me still feels a bit guarded about liking this game so much. So does 2024 me, to some degree, though I’m old, cantankerous, and shameless enough not to care.

Not this is not necessarily because I think anyone would say that Final Fantasy VIII is bad, mind you. I feel like Final Fantasy VII’s long shadow not only obscures, but protects the two games that followed it. The same knee-jerk Playstation apologists arguing for the superiority of their console over the N64 would gladly include Final Fantasy VIII and IX in their generalization of “serious games for grownups”. But if you asked one of them, “What makes Final Fantasy VIII grownup?” there might be some fidgeting before you get an answer.

Let’s just come out and say it: Final Fantasy VIII is a love story.

And if Final Fantasy VII was some kind of perfect expression of teenage-boy angst and power-fantasy fulfillment, attracting millions of similarly-disillusioned teenage-boy fans, Final Fantasy VIII kicked them in the teeth with a love story and they frankly did not know what to do with it.

Love stories are girl-stories, after all. Not sure if you heard.

But it’s not that simple, is it? If it was just Meg Ryan Romantic Comedy: The Video Game, they could have just chucked it out the window and been done with it. But Final Fantasy VIII features an angsty teenage badass with a sword which is also a gun, who has this deep, manly rivalry with another angsty teenage badass with a sword which is also a gun! And they’re both mercenaries who go on special ops missions with their friends who are similarly bad-ass and well-equipped! And there’s a secondary character with an assault rifle! And Final Fantasy’s usual complement of monsters and dragons and cool, power-fantasy spells and summons and so on, all with these awesome cutscenes featuring action scenes and battles and cool poses and…

Final Fantasy VIII remains a love story.

Look, I want to get to the deep thematic analysis of this game as much as anyone, but I have to drive this point home first: Western audiences—especially teenage boys enamored with Final Fantasy VII—did not know what to do with Final Fantasy VIII.

But spare a thought for the developers at Squaresoft for a moment. Figure Final Fantasy VIII had been in the works for a while when suddenly 1997 hits and Final Fantasy VII is the biggest game on the planet. Squaresoft now has all the money in the world and a cultural mandate to do whatever crazy thing they want to do, so long as it’s bigger and better than Final Fantasy VII. And that is no problem—they were basically inventing the 3D JRPG with FFVII, and innovation and iteration is very much their bread-and-butter since Final Fantasy II. It should be no problem to make a bigger, better game.

What’s more, Final Fantasy VII was already a big swing: a huge aesthetic deviation from their past games, not just by necessity of the move to 3D, but by moving to a more contemporary setting, employing big CG cutscenes, emphasizing downtime in the sprawling Midgar city, and getting even more creative with big set-piece moments. Suddenly Squaresoft is the studio for video-games-as-art, and everyone is expecting them to make a masterpiece.

So they steer hard into the wind. If they’re artists now, they’re going to make some art, dangit. If they are the biggest innovators in gameplay, they’re going to give people something they’ve truly never seen before.

This is it. Time to let out all the stops. Final Fantasy VII put them at the top of the world: everyone is waiting to see what they do when they get there. Time to make the statement. The game that people will remember forever. It’s magnum opus time.

All this to say that I think there was a fundamental miscommunication at play here. Final Fantasy VII means a lot of different things to different people, but the mass of new fans who had never played a Final Fantasy game before were not necessarily excited about its artistic aspirations or gameplay innovations. For many, they were excited that it looked cool, had edgy dialogue, and neatly inhabited the narrow space where “art” and “male teenage angst” overlapped (a consistently winning formula in the late ‘90s: it’s no accident that the following years also gave us Fight Club and The Matrix). But for the developers, Final Fantasy VII was a daring step into the future of the franchise, and opened up some serious new artistic spaces to explore.

Like love stories, for example.

Final Fantasy VIII: The Basics

There’s a lot I want to say about Final Fantasy VIII, but the trick here is going to be organizing those thoughts. So let’s start with the big picture, and then we can narrow our focus and talk about the details that compose that big picture.

So if I had to point out what, most obviously, makes Final Fantasy VIII unique among all the other games that came before (and after, for that matter), I think there’s one key word to keep in mind.

Grounded.

Final Fantasy VIII is the most grounded of all the Final Fantasy games.

Now this may sound like a strange thing to say about a game that features a plot point about releasing a sorceress trapped in a magically-sealed bubble orbiting the moon so a different sorceress from the future can mind-control her and compress time, but remember that this is a game franchise that has actually visited the rabbit-people who live on the moon, so we’re clearly dealing with a sliding scale here.

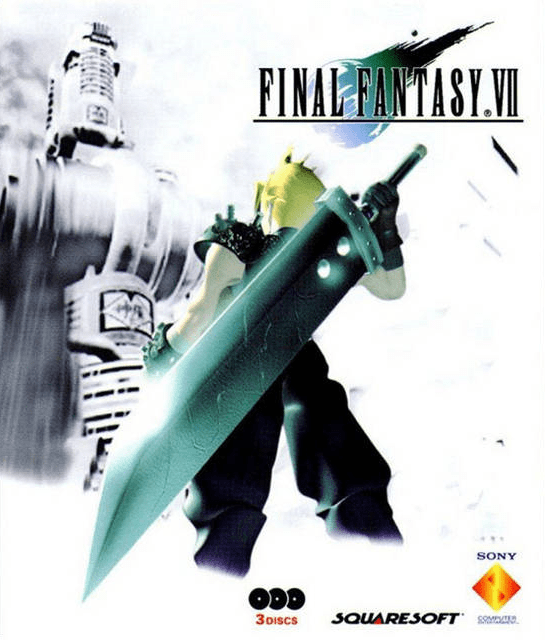

But for more evidence, I need only point you to the first experience with the game you’re likely to have. Namely, the box art.

Look at the difference here. Final Fantasy VII is clearly promising a dark, manly adventure: the tower of Midgar looms over Cloud, who stands with his back toward us to indicate that he’s a brooding, mysterious loner—and which also conveniently showcases his absurdly oversized sword. The tower is monochrome while Cloud’s yellow hair contrasts strikingly: he is the hero facing this menacing symbol of conformity and oppression.

But the cover of Final Fantasy VIII promises: character drama. Squall and Seifer stand facing opposite directions, with Rinoa between them, hinting at the love triangle at the core of the game’s narrative. Rinoa is in profile, facing the same direction as Seifer, but her face is turned toward us, indicating at her accessibility and friendliness, as well as her difficulties choosing between the two men. Seifer, by contrast, is turned away from us, ever the rebel, staring defiantly into his own middle distance. And Squall, while also turned to the side (though opposite the other two characters), faces the same direction as his body, indicating his forthrightness. Note, too, that both Squall and Seifer’s positioning showcases their matching scars.

We should also note that the background art is purple: warmer and softer than Final Fantasy VII’s stark monochrome tower. We can see sorceress Edea, garishly outfitted, looming over the three characters with a gesture both maternal and open (hands at sides, as though inviting a hug), but indistinct (increasing menace).

And then there’s the title logo: Squall and Rinoa embracing. Not the Meteor of Final Fantasy VII, or the fantastic steampunk mech of Final Fantasy VI, or the crystal of Final Fantasy IX, or the various characters in garish armor that defined many of the earlier games.

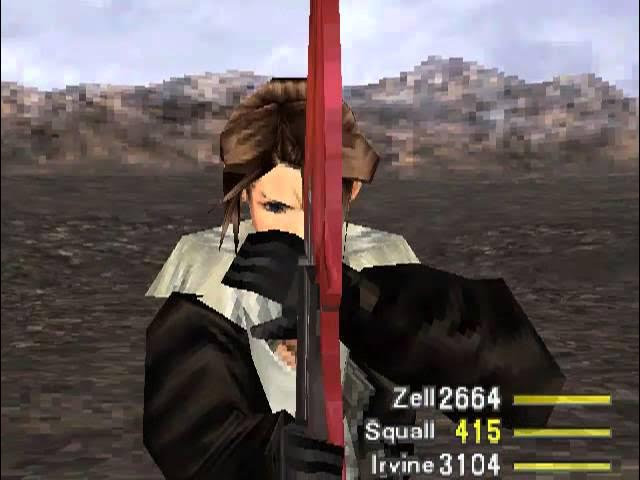

Which brings us to an even more fundamental design principle here in Final Fantasy VIII: more than any other game to date, the characters are meant to look relatable. Gone is the fancy dragon armor of Final Fantasy IV, or the garish outfits that indicated jobs in Final Fantasy V. None of the characters wear anything resembling armor, or have any characteristics that would alienate them from their audience. The move from Final Fantasy VII’s cartoonish character proportions to the effort at photorealism evident in Final Fantasy VIII is especially noticeable. Gone are Barrett’s gun arm, Cloud’s massive Buster Sword, Tifa’s disproportionate bust, and whatever is going on with Vincent. Final Fantasy VIII outfits are stylized, but plausible: Squall’s bomber-jacket-and-T-shirt, Rinoa’s sleeveless sweater-dress-cape thing, Irvine and Seifer’s trenchcoats—all represent a much more narrow deviation from realistic contemporary fashion.

The six party characters are not only recognizably human, but have clear human proportions and behaviors. Their facial expressions are unreadable (a limitation of PS1 hardware), but great pains have been taken to make their gestures readable without resorting to cartoonish exaggeration or the non-diagetic emotional cues typical of manga or games past. Selphie and Zell are afforded a certain amount of exaggerated posing (like Zell’s ashamed crouch, or Selphie’s hop-and-fist-pump), but the other characters (especially Squall and Irvine) tend to have understated animations to express their feelings: Squall’s facepalm, Irvine’s casual hand-wringing gesture, Quistis’ bossy hair flick.

Gone, too, are many of the most fantastic elements from the franchise. No steampunk airships or alien landscapes emphasize the strangeness of the world: in the first three hours of the game you will spend most of your time wandering around Balamb garden (we’ll get to that in a moment), and the strangest things you’ll encounter are:

- The GF’s Quezacoatl, Shiva, and Ifrit (all of whom are franchise mainstays, or close to it)

- Various monsters like Bombs, Buer, or the snake monsters on Dollet’s slopes

- Elvoret the tornado monster atop Dollet’s communication tower

- The giant robot that chases you back through Dollet

Most of the enemies are soldiers, wielding swords or guns. The boats you use to travel from Balamb to Dollet would not look out of place in a modern espionage thriller, and all the action that takes place in the two major early cutscenes—Liberi Fatali and Attack on Dollet—are easily related to contemporary action fare. Even the setup: Squall is studying at a school for mercenaries, is a bit fanciful, but not implausible, especially given the familiar elements of the school setting like uniforms, dormitories, classrooms, etc. All of this is supposed to be familiar, grounding.

And Balamb Garden is the key to making this work.

Balamb Garden

Final Fantasy has some of the most famous and outlandish opening sequences in the history of gaming. Final Fantasy IV opens with The Red Wings—one of the greatest musical compositions in Nobuo Uematsu’s early history—and follows Cecil as he commits a war crime for his liege. Final Fantasy VI opens with mind-controlled Terra’s harrowing journey to Narshe, which will set the stage for her own guilt in the game to come. And Final Fantasy VII opens with the Bombing Mission, where Cloud joins Barret’s band of revolutionaries as they try to destroy a train station to undermine Midgar’s military authority.

And, somehow, Final Fantasy VIII manages to both top all of these, and deliver something much more grounded and relatable.

Part of the secret is Liberi Fatali: one of the most iconic and rousing musical compositions and cutscenes in the history of the franchise, if not all of video game music altogether. Seriously, I defy you to watch Liberi Fatali and NOT get pumped for the game that’s about to transpire.

But the other secret is Balamb Garden.

See, Liberi Fatali is justly loved. It absolutely promises excitement and adventure to come, introduces the central characters, sets up the rivalry between Squall and Seifer, Rinoa as Squall’s girl-next-door love interest, and even some of the deeper thematic material (which we’ll get to, don’t worry), but notice that it does all that without using any of Final Fantasy’s usual otherworldly elements. Besides the surreal feather imagery, the only “fantastic” thing that happens is when Seifer casts fire on Squall during the fight, and this is clearly framed as cheating (which also sets up Seifer’s character). But shots like the spinning sword crashing to earth, Squall and Seifer’s exchanged wounds, Edea’s magisterial menace: they all are relatable—plausible—but rendered hyperkinetic and exciting when backed by that pulse-pounding, relentless Uematsu score. It’s mysterious, thrilling, surreal, and informative, all at once.

But Balamb Garden is usually considered, well, boring, by contrast.

See, we come off that killer cutscene, and the next shot is—Squall lying in a bed, recovering from his injury. So we know that the fight from the cutscene was real (presumably the rest was not), but we are still eager to find out what’s going on with the creepy sorceress and girl-next-door in blue. Which is good, because the game is going to insist we chill out for the next hour or so while it teaches us how the game works.

And there is a lot to teach.

So, naturally, they dump us in a classroom. Squall has to go sit in class and listen to Quistis lecture. Then, worse yet!—turns out today is his big exam in the fire cave, and we have to listen to Quistis drone on about Junctions so we can fight some dudes and get Ifrit to join our team.

OK. We’ve already got a lot to discuss here. So let’s break it down.

- This might actually be the slowest opening in Final Fantasy history, if you ignore the Liberi Fatali cutscene. Heck, even the first game kicks off with you going on a mission for the king. Final Fantasy games usually prefer to give you active Tutorials: teach on the fly. But here, we slow waaaaaay down in order to give the player time to find their feet. The game won’t even let you fight monsters until you’ve figured out how to navigate Balamb Garden, junction your GFs, save the game, etc. Which is good, because the Junction system is a lot less forgiving than battle systems past (but we’ll get to that, too).

- Notice, though, that the harsh transition from Liberi Fatali to Balamb Garden actually puts us in the same position as Squall. The player, too, is irritated and disappointed that they can’t jump right into the action. That cutscene promised us excitement, dangit, and now we’re stuck wandering around a cross between boarding school and a modern hospital, doing homework and playing card games. Like Squall, we want to get through the busy work and get on with our lives. Like Squall, we’re irritated with Quistis’ lectures and want to skip to fighting monsters. Insofar as this gets us moving the plot along, this is absolutely what the developers want us to do. (Though I imagine this has the unintended side effect of causing players to skip through all the tutorials, which will cause problems for them later.)

- The music for Balamb Garden is criminally underappreciated. Fisherman’s Horizon is usually held up as Uematsu’s chill-music masterpiece from Final Fantasy VIII, but that ignores just how much work the Balamb Garden theme does to establish the world and Squall’s relationship to it. The theme is quintessential “home” music: familiar, but a little institutional. Calming, but not cloying. By Disc Two, when you’ve only been able to make it back to Balamb after failing your mission, narrowly escaping prison, fighting your way through a military base—only to find the place in grave danger, not just from the missile attack, but the internal war between the Headmaster and the Garden Master: when, after all that, you first get to hear the familiar Balamb Garden theme, it’s amazing how comforting and familiar it seems.

- This also makes the fire cave feel better than it is. The fire cave is just a tutorial dungeon: you go in, fight some monsters, learn more about junctioning, and fight a pretty easy boss. But because you’re finally getting to the action of the game, it’s easy not to mind Quistis’ lectures, the tedious Junction business, or the low-level enemies. You’re just glad you’re not in class anymore. Then when it turns out that you not just beat but capture Ifrit, making it so you now have three GFs to summon—well that just feels amazing.

- Which in turn just sets up the Attack on Dollet sequence—the literal final exam—which is just thrilling start-to-finish (and I say that knowing perfectly well that cooling your heels in the town square while Seifer gets impatient with your inaction is a major plot beat), and feels amazing after playing in the Balamb kiddie pool.

The Liberi Fatali/Balamb Garden transition is immaculate. Cumbersome as it seems at first blush, it actually makes for the strongest opening to a Final Fantasy game to date—and I doubt it’s been outdone since.

Which is good, because the Junction system is probably the most complicated battle system Final Fantasy has ever produced.

Con: Junction Junction, What’s Your Function?

That was terrible, and I 100% stand by it.

Talk to Final Fantasy fans about Final Fantasy VIII and you’ll get three major critiques (aside from the love story thing, which nobody will admit).

- The Junction system is fiddly and complicated and boring and I never figured out how to use it/never cared to optimize it.

- The story goes completely haywire in Disc 3.

- The Card Queen Quest sucks.

I’m just going to capitulate to (3). The Card Queen Quest does suck. I don’t think I’ve ever actually finished it all the way through (though I got very close on this last play-through). Triple Triad, as a rule, is actually weirdly engaging for a diverting in-universe card game (probably the first of its kind), but the Queen sends you grinding through all sorts of bad situations where you can lose valuable cards by accident…it just sucks.

But I do want to talk about the Junction system, because I think it’s really interesting. And I do want to talk about the story, because I’m growing less upset about it in my old age.

So the Materia system revolutionized combat in Final Fantsy VII. Before the Materia system, combat customization was limited to:

- Who’s in your party? (Final Fantasy VI)

- What have they equipped?

- What job do they have? (Final Fantasy I, III, V)

However, in Final Fantasy VII you can dramatically customize what skills and spells a character has, what summons they can use, how they react to certain battlefield actions, how attacks work—all by cleverly allocating your materia. It’s powerful, accessible, tied to the overarching plot and themes: 10/10, no notes.

But it’s magnum opus time, remember. Time to give the player more power, more flexibility.

So in many ways, the Junction system is the logical endpoint of any stat-based JRPG: we’re just going back to the spreadsheets of Dungeons and Dragons.

That’s not entirely true, but the principle is similar. In Final Fantasy VIII, your spells are a finite resource you can allocate, rather than a constant skill that pulls from a finite mana pool. If you want to cast cure, you need to find and collect (draw) cure spells.

But you can also take those cure spells and Junction them to a stat—Junction 100 cure spells to your Spirit, and you’ll be more resistant to magic attacks from enemies. Junction Fire to your Elem-Atk, and you’ll do fire damage when you attack enemies. Junction Blizzard to your Elem-Def, and you’ll take less damage from ice spells.

Compared to the material system, this is a massive increase in customizability. The Junction artist can create a team where every character has max (9999) health, does ridiculous status effects (like Death or Stop) on attacks, and is immune to/absorbs virtually every kind of elemental damage, before they even hit level 50.

(This is how I play Final Fantasy VIII, by the way. I break this system wide open.)

The trick is, you have to spend a substantial amount of time drawing spells from enemies. The best spells tend to come from the nastiest monsters, so the power player will spend a substantial amount of time during boss fights drawing spells rather than actually trying to defeat the boss. This makes for some pretty tedious individual fights. So, for example, when I fight Elvoret—the boss on the top of the Dollet communications tower—I usually end up sitting there for half-an-hour or more, drawing 100 Double for each of my characters, because it’s a really useful spell with powerful junction potential, that you won’t find easily for hours into the game. Likewise, it’s not abnormal to stop the game in its tracks for fifteen minutes to draw spells from some random new monster you’ve encountered, virtually every time you enter an unfamiliar area.

This rubs a lot of players the wrong way, but I’ve never minded it too much. The main reason is that it doesn’t seem like any more work than the average Final Fantasy game asks of its players: it’s just oriented differently.

Virtually every JRPG requires a certain amount of grind. Every time you enter a new area, your characters are expected to be at a certain level. If you’re beneath that level, you’ll probably get your butt kicked a few times until you go back to an earlier area, kill a bunch of more manageable monsters, then try the new area again.

However, in Final Fantasy VIII, your level isn’t actually a major indicator of your strength. Junctioning can power up your stats significantly more than leveling. And since monsters level with you (and level experience caps are fixed), there really isn’t any advantage to power-leveling your characters, especially in the early game. So if you enter an area that kicks your butt, going back and grinding won’t help, but you can just move some of your magic around until you can take on the threats. Or you can squat in a single fight, drawing new spells, so you can increase you stats more significantly. You don’t need to grind enemies to raise your level: you need to grind spells so you can raise your stats. You don’t need to fight a bunch of enemies and beat them; you need to be able to keep one fight going long enough to get all the spells you want.

So I don’t think there’s a major difference between the amount of time and effort required to grind spells in FFVIII vs. grinding levels in FFVII. But I will admit that there’s a psychological cost here. Fighting a bunch of monsters to watch your level go up feels like you’re accomplishing something more than watching your characters draw Double from Elvoret for twenty minutes.

But I actually think that drawing Double is the greater challenge. Fighting low-level monsters for twenty minutes to bring up your level is tedious and uninteresting: you fight some mook who poses no challenge, heal up your party, repeat until you’re at the level you want, saving occasionally throughout. But keeping your party upright while you collect all the spells you need from a boss who is trying to kill you is a real challenge. It’s a challenge that can go horribly wrong: there’s nothing more frustrating than drawing half the spells you need only to miscalculate and have the boss kick you back to the last save point—but it remains a challenge. And I think that’s what the developers at Squaresoft had in mind.

Though I don’t think that’s all they had in mind.

Sorceress Who Now?

Let’s talk story for a minute, since I think these two problems are actually deeply connected.

Final Fantasy VIII is about six teenagers in mercenary school. In the first few hours of the game they take their exam, pass, and become full-fledged mercenaries contracted for Garden, the organization where they’ve been taking classes for the last years (except for Seifer, who fails for insubordination). At graduation, Squall meets Rinoa: the hot girl-next-door from the Liberi Fatali sequence, and falls for her a little, even though he’s not interested in a relationship right now, what with being too angsty and aloof all the time. She hires him and his two buddies to go on a mission for her resistance movement, but the whole thing is a mess, and gets interrupted anyway when they get a call from HQ: they are hired to assassinate sorceress Edea.

It’s not clear what the deal is with Sorceress Edea, but it’s clear she’s bad news, and is a figurehead for fascist government Galbadia. So they pick up a sniper, Irvine, and set up the mission, but the whole thing goes horribly wrong, Seifer turns out to be working as her bodyguard, and the whole team is captured and imprisoned. They bust out, only to find that the Galbadians are retaliating against Garden. The team narrowly manages to save Garden from the attack, but it turns out that Sorceress Edea and Galbadia have taken over one of the other Gardens (which are now mobile) to spread fascism throughout the world. The two Gardens fight, Edea is captured, but not before she incapacitates Rinoa. Squall, now forced to face his feelings for Rinoa, takes her to the mysterious Esthar continent for treatment, where it turns out that the reclusive Esthar-ians have wildly advanced science and technology, but they can only treat Rinoa by sending her and Squall to their lunar space station. While there, Rinoa suddenly becomes active (turns out she was a sleeper agent!), and releases the other sorceress, Adel, from her space-prison. Squall decides to save Rinoa rather than himself, catches her as she plummets through space, and by sheer dumb luck they find a spaceship, take it over, and fly back to the planet to regroup and fight Adel.

Still following? OK. Because it’s about to get even weirder.

Turns out, this whole series of events has been orchestrated by Sorceress Ultimecia, some rando sorceress from the future, who was mind-controlling first Edea, then Rinoa, and now is trying to control Adel, in order to cause Time Compression and rule the entire universe by causing past, present, and future to all occur simultaneously. The team decides to walk into the trap: they offer Rinoa as bait, Compress Time, attack Ultimecia at her future-fortress out of time, and defeat her.

Go get a sandwich. You earned it.

Look, I’m not going to deny that a lot of this plot is nonsense, and that it’s not at all grounded the way I discussed the first few hours of the game. The Ultimecia gambit seems especially nonsensical, seeing as she comes out of nowhere, doesn’t show up until the final boss fight, and has no preexisting relationship with any of the other team members or interaction with the rest of the world.

But (1), remember that this is a sliding scale. Visits to the moon are relatively common in this franchise, and so are last-minute-reveal villains with nigh-omnipotent power.

And (2), while this might not make a lot of rational narrative sense, we’ve been primed (by Liberi Fatali) to read the emotional and thematic sense. And that reads clear as day, at every beat of this game.

Let’s tell the beginning of the story again, but this time, let’s focus on the characters and not the plot.

Squall is our main character. He has a rivalry with Seifer, who goads him into a schoolyard brawl with swords, and both end up hospitalized. They also end up on the same team for the final exam at Dollet, where Seifer is given command of Squall’s unit, then violates orders to hold the town square, preferring to abandon his post and attack a different target because he’s bored. Squall begrudgingly follows orders, and even tries to rescue Seifer when new orders arrive to evacuate the city, but resents Seifer for sabotaging his team. Despite this, Squall passes the exam; Seifer fails, not for the first time, and his grudge against Garden intensifies. But that night at the graduation ball, Squall meets Rinoa and falls for her, finding out only later that she has a pre-existing relationship with Seifer.

Rinoa thinks Squall is cute, too, and teases him for being aloof. Turns out, she’s putting together a mission, and specifically requested Squall to help her achieve her ends in the Timber resistance. Squall thinks the whole mission is an ill-considered unprofessional mess, and that Rinoa is a terrible leader, however enthusiastic, but follows orders despite his misgivings. As the mission unfolds, though, it turns out that Seifer has gone ahead in an unsanctioned effort to achieve Rinoa’s goals, and is adopted by Sorceress Edea as her bodyguard—the sorceress’ knight, he calls himself. Squall reports to the local garden in the aftermath of the fiasco, only to discover that Seifer has been executed by Galbadian officials, which leaves Squall questioning his actions, Seifer’s actions, and the nature of their relationship, especially since Rinoa is beside herself with guilt at the news. But Seifer is NOT dead, and Squall must face off with his rival to accomplish his new mission to assassinate the sorceress.

Even in Disc 3, as the plot logic goes off the rails, the emotional logic remains a solid throughline for the characters. When Rinoa is incapacitated by Edea, Squall cannot deal with the loss, and desperately goes to Esthar for help. No matter how ridiculous shooting them into space may seem, Squall’s desperation remains true to his character. As mad as his rescue of Rinoa in space may come off in summary, in-game it’s a painfully heartfelt, understated moment: two bodies flying through space in a last-ditch effort to reach one another and be together, if only briefly.

The entire story, start-to-finish, is grounded in Squall’s growing emotional honesty, his willingness to trust Rinoa and his friends, and his development as a leader, to those close to him, and to all of Garden. Where Seifer grows more and more distant from the other people in his life, becoming more and more isolated as he follows his myopic dream, Squall learns not to be alone, to rely on others (and not just himself), and that most obviously in his growing love for Rinoa.

I love the arch characters of Final Fantasy past: Cecil, Galuf, Terra, Celes, Cyan, Cloud, Tifa, and many of the others make for great, memorable, affecting moments and story beats. But I don’t think any Final Fantasy character is more richly characterized or relatable as Squall in Final Fantasy VIII. Where Cloud was a character that resonated with teenage boys, Squall was a teenage boy: angsty, disaffected, morose, self-isolating—which counter-intuitively meant that teenage boys liked him less.

I like to think I was honest enough with myself, even as a teenager, to appreciate the nuance of Squall’s characterization. To recognize his heroism in contrast with Seifer’s villainy. To see that Laguna’s goofy, unplanned love for Raine and Ellone was appropriately aspirational for Squall (I swear, I cry every time during the Winhill sequence). And to see that Squall had to get over himself in order to properly win the girl and the game.

But we’re still one layer out from the real depth this game offers.

Time Compression

There’s a scene in Disc 3 where Dr. Odine explains the whole plot to us. Where we find out about Time Compression, Sorceress Ultimecia: everything that will define the last hours of the game. And it’s pretty terrible. Odine’s character design is off-putting and weird, the delivery is just straight exposition without any action, and we have no idea who this random Sorceress is, much less what Time Compression is supposed to be.

But half-focus your eyes, pay attention to the tone not the words, and things start to become clear.

Time Compression is, symbolically, the abolition of time. Sorceress Ultimecia wants to eliminate time’s progressive nature. She wants to rule, in perpetuity, eternally.

I’m reminded of some of Nietzsche’s thoughts on philosophy: how Plato and his successors held up the eternal, lauded and celebrated it, and considered the transitory and sensory to be somehow inferior because it was subject to change and decay. In Twilight of the Idols, Nietzsche writes:

These senses, which are so immoral in other ways too, deceive us concerning the true world. Moral: let us free ourselves from the deception of the sense, from becoming, from history, from lies; history is nothing but faith in the senses, faith in lies. Moral: let us say No to all who have faith in the senses, to all the rest of mankind; they are all ‘mob.’ Let us be philosophers! Let us be mummies! Let us represent monotono-theism by adopting the expression of a gravedigger!

Nietzsche sees the virtue of the transitory. He loves change. He loves life in its messiness. And I think the developers at Square would agree.

Throughout Final Fantasy VIII, Squall struggles between the principle he has devised for himself and the reality transpiring in front of his eyes. He is a loner. He does not trust others, because he does not want to be disappointed by them. It is a very Buddhist outlook, a very stoic outlook, a very philosophical outlook. But it is revealed through the course of the game that this is the result of childhood trauma. Squall was “abandoned” by his “sister” Ellone as a child, when he lived at an orphanage. And so he swore not to rely on others, to instead trust only himself.

As Nietzsche would be quick to point out: Squall has adopted an eternal philosophy because of some kind of temporal weakness or distrust. He is not enlightened, he has developed a philosophy based on a bad idea, then forgotten where that idea came from, and thus concluded that the idea must be correctly universal.

But Rinoa is not some eternal being. She’s not even terribly trustworthy. She will inevitably let Squall down—and does: his attachment to her causes him to behave irrationally, causes him pain when she is gone. But she brings him joy beyond any he feels in his philosophical isolation. But that joy only exists moment-to-moment. It is not some kind of eternal, changeless joy.

To properly feel this way, Squall must abandon his atemporal principle and live in time. He must enjoy the time they have together, despite the fact that it will almost certainly end, causing terrible pain to one, the other, or both. He must trust her, not just to love him, but in spite of the fact that she will let him down. Our last glimpse of Laguna in the closing cutscene—the final shot before the credits roll—has him at Raine’s grave, smiling: Time Compression might have brought them back together, but he is against it nonetheless. Better to have loved and lost than never been able to love at all. Squall’s future is uncertain, but death remains assured. That assured death is a small price to pay for an uncertain future with the person he loves, with his friends, and with the possibility of building their relationships together.

And Ultimecia not only wants to destroy that, she wants to destroy the very possibility of a relationship like this. The chance meeting at the graduation party would be impossible in a world without time. The ability to change and overcome one’s childhood traumas, could not happen without time’s progression. Trust, love, friendship, and growth are all things Ultimecia wants to eliminate from human experience.

But, as Squall learns, they are the only things worth valuing. Once Ultimecia is defeated, Squall must face one last peril: succumbing to his own fears, and reverting to his childhood self, rather than trusting Rinoa and following her into temporal reality. Once time is restored, his first attempt goes awry. He returns, not to Rinoa, but to his childhood trauma. Then he is stranded in time, trying to remember Rinoa and failing, interrupted by his fears and insecurities. The visual signifiers of that last cutscene are abstract and ambiguous, but the emotional language is clear: What if she isn’t there? What if she never existed? What if it goes wrong? What if all those narrow escapes fail? What if that relationship isn’t real? What if I don’t actually know her? Ultimately Squall can’t overcome his doubts. He’s lost in time.

But it doesn’t matter. She finds him. Squall may be a mess of doubts and insecurities, but Rinoa’s path is clear. Whether or not he trusts Rinoa, he can trust her.

Turns out, he can trust her more than himself.

Take that, little kid Squall.

Themed Mechanics

So let’s take a moment to look at the Junction system again. Remember that optimal play involves keeping a boss fight going as long as possible, stalling the conclusion, good or bad, until you’ve taken all the spells you can out of the encounter.

There are a few ways we could interpret this choice. Perhaps this represents an Ultimecia-esque effort to eliminate the passage of time: a confirmation that power only grows in some kind of eternal context. A thesis that would be buttressed by the fact that Guardian Forces offer power to the characters, but at the cost of their memories. The power to change their circumstances comes at the cost of their ability to see time progress naturally, to grow and change organically in time.

Or we could see this as a positive choice. If we compare the act of stalling a boss as long as possible to holding on to a moment in time—say, savoring Squall’s time with Rinoa on the bridge of the Ragnarok, before they are summoned back to earth—we could see this as learning to make the best of our time, working to sustain a delicately balanced relationship (between the threat of the boss and the growth we desire) in a live-fire environment. Gain is not eternal (like grinding levels), but tenuous and subject to change (choosing to store or use spells).

Likewise, consider the way Limit Breaks work in this game. In Final Fantasy VII, taking damage gradually charges your Limit Break, at which point you can use one big scary move to do a ton of damage, or healing, or what have you. But in Final Fantasy VIII, if you are at low enough health, you can use Limit Breaks all day long. You just have to sustain it. Keeping Squall at low health is dangerous, but if you pull it off, you can use Renzokuken dozens of times in a row for massive damage. If you can keep Selphie barely alive for a while, you can slot Full-Cure and heal the whole party up to full health, or The End any enemy in the game. As in life, vulnerability is power. Squall is at his most dangerous and powerful when he faces his fears and allows for the possibility of failure, rather than try to prepare and guard himself against anything bad happening.

The smart, safe Final Fantasy VIII player is also consistently the weakest. Truly optimal play involves taking risks, making dangerous choices, and allowing for failure. Grinding in safe spaces is not a valid solution, and it is in fact to your advantage to keep your levels low until you get stat-modifying abilities like Str and Mag Up to make your gained levels most worthwhile.

The interpretation is ambiguous, but one thing is clear: Squaresoft wants us to think about time. The Junction, Limit Break, and leveling systems were designed with the intent of forcing us to think about battles differently and encourage us to interrogate the way we interact with the game world. Growth is not simple or linear in Final Fantasy VIII: that’s the point. It must be protected and maintained, just like any relationship.

Whether or not you like the love story of Final Fantasy VIII; whether or not you find the Junction system tedious; whether or not you think the Time Compression plot is silly or absurd: I believe it is unquestionably intentional. These are calculated choices toward an intended effect, successful or unsuccessful. And Final Fantasy VIII is less interested in its grand plots, its spectacular effects, and its power fantasies, than it is in delivering its thesis on love, trust, and time. Everything else is focused on that one goal.

Wait, What Were We Talking About Again?

Oh, right. We’re supposed to be comparing and contrasting here.

Look, I think I’ve made my case for Final Fantasy VIII’s artistic merits and clear intentionality. I think it’s masterfully paced, beautifully scored, and carefully designed at every level of play. I think the characters are wonderfully realized, even if the plot goes a bit off the rails. I think that even its missteps are bold, calculated, and fascinating. I think this really was intended to be the definitive, magnum opus follow-up to Final Fantasy VII, grounded in a reality and relatability that Final Fantasy VII often lacked, and I think that it sought an artistic integrity few games had even known they could aspire to, much less attempt to reach. I think it has some of the most affecting moments of any game I’ve played in the franchise, that it only rarely misses its emotional goals, and looks dang good doing it, most of the time.

But I don’t think there were a ton of people who agreed with that assessment when it first came out in 1999.

I doubt anyone actually thought it was a bad game (fiddly Junction system and wonky third act notwithstanding), but it certainly did not hit Western audiences the same way Final Fantasy VII had. And I really think part of that comes down to Western audiences being pretty immature at the end of the day. Yes, Final Fantasy VII has a more immediately understandable plot and conflict, and Sephiroth is possibly the greatest villain in video game history, but Final Fantasy VII appealed to a teenage boy audience in a way the Final Fantasy VIII just didn’t. Final Fantasy VII met us where we were at; Final Fantasy VIII expected us to be better than we were.

So I imagine the attitude around the Squaresoft offices in 1999 was complicated. Probably more than a little baffled and disappointed at the lackluster reception. This was the bigger swing, the more daring artistic endeavor: artists and writers and programmers all poured heart and soul into a game fundamentally about emotional vulnerability and taking risks for the things you care about, and the response was:

“Meh. Not as cool as the first one.”

This, to me, is the moment of tragedy in the career of Final Fantasy. There have been great games since, but they have all been informed by the lesson Final Fantasy VIII’s “meh” response taught:

Spectacle over subtlety.

If grounded was the watchword of Final Fantasy VIII, I don’t think we’ve seen any game come out of Squaresoft/Enix that revisited this priority. All the Final Fantasy games since have gone to greater and greater fantastic lengths, embracing more and more dramatic spectacle than the one before. They’ve been sold on the strength of dynamic, eye-popping cutscenes and “cinematic” storytelling, rather than intimate character drama. And that’s not to say that there aren’t good characters or good stories in these games, just that the fans want spectacle first, and each new trailer or ad or promotional release will promise just that.

What I loved about Final Fantasy VIII were the slow, quiet moments: futzing about Balamb Garden or Fisherman’s Horizon, Squall wrestling with his complicated feelings about Seifer after his supposed death, and Laguna at home with Raine and Ellone. Even more than Liberi Fatali, or Time Compression, or the absurd summon animation for Eden, these moments have stuck in my mind since the first time I played this game through. And I don’t remember anything close from my outings with IX, X, XII, and XIII.

It just wasn’t a priority anymore.

In 1997, there was no game like Final Fantasy VII. By 1999, Ocarina of Time had dethroned the king, System Shock 2, Fallout 2, and Planescape: Torment were setting new standards for video game storytelling among Western audiences, and Donkey Kong 64 could look great in-engine without pre-rendered cutscenes. It was a new world. The bar had moved.

Further complicating things, Sony had just announced the release of the PS2 in 2000, and that meant new specifications to consider, new standards to reach. A new Final Fantasy game would be the game that would keep PlayStation audiences coming back to the new console, so you can bet there was pressure on Square to turn out something great for the new hardware.

So I imagine that poor little Final Fantasy IX really didn’t have a chance.

Final Fantasy IX’s Lame Duck Syndrome

Final Fantasy IX was released in June of 2000, a scant few months before the release of the PS2 in late October, and barely a year before Final Fantasy X in July of 2001.

I have to imagine that Square had been working on the game for a while, concurrently with Final Fantasy VIII, just in time for Sony to announce the PS2 and work to shift focus to Final Fantasy X. FFX definitely shows the polish that FFIX lacks, and FFIX often feels a bit half-baked by comparison to both VIII and X.

I’m honestly not sure what history thinks of Final Fantasy VIII and IX in hindsight. I doubt I’m the only one who considers VIII an unsung masterpiece, but I’m not sure how many staunch defenders of IX are out there, making their case. Overall, I suspect that the perspective remains what it was in the early 2000’s—these are the middle children of the franchise, nestled between the wild breakout successes of VII and X, worth less comment together than either VII or X does alone.

That’s not necessarily fair to these two games, both of which show a great deal of care and effort. But I’ll admit, I’m much more staunchly a defender of Final Fantasy VIII than I am of IX.

Heck, I don’t really even like IX all that much.

And I tried to. Really, I did.

I want to say that I tried playing Final Fantasy IX at least three times over the years. The first time was likely in high school or college. I think I made it as far as the Iifa tree on Disc 2, and got stuck on the battle there, gave up, and didn’t go back to it. I may have made another attempt in those years, but I honestly don’t remember.

I do remember playing it again in 2008 for my big Final Fantasy playthrough. I think I got as far as Disc 3 this time, because I can definitely remember Garnet’s big hair-cutting scene, but I don’t remember Terra well, and probably got stuck on one of the boss fights either just before or just after entering Terra.

But I did in fact want to correct this hole in my Final-Fantasy-ography, so I spent this past August making another attempt at the game and did, in fact, beat it this time.

But I did not enjoy doing it, and succeeded mostly on the strength of sheer determination.

I will say, now, though, that I’m glad I did it.

So let’s talk about Final Fantasy IX

Since this is generally going to be pretty critical, we should start with something nice: the opening.

Final Fantasy IX opens with a play: “I Want to Be Your Canary.” But the play is a front for a plot: Zidane and his merry band of thieves have come to capture Princess Garnet for ransom. But the princess doesn’t need to be kidnapped, she was apparently hoping to stow away with the theater troupe because she’s worried something is going on with her mother Queen Brahne. Along the way they pick up Vivi, a child-sized black mage, and Steiner, the overzealous captain of the Pluto Guard who swears to protect the princess. Together they escape the castle only to be shot down by Queen Brahne and stranded in the Evil Forest.

Start-to-finish, this sequence is delightful. Puttering about Alexandria with Vivi is a bit of a low point, especially since it’s not clear what you need to do to progress, but most of the time is spent in mock swordfights, back-room plots, or watching overdramatic actors ham it up on stage. The whole thing culminates in an especially ridiculous climax: Princess Garnet, Zidane, Vivi, and Steiner all end up on stage, where Zidane and Garnet ad-lib their way through a scene while Steiner hopelessly stands by, paralyzed by stage fright. It’s silly, propulsive, fun to play, and quietly tutorializes much of the game, including combat. Masterful work, all the way through.

It also really showcases the new level of technical acumen on display in this game. Final Fantasy VII suffered from displaying cartoonishly disproportionate characters against frequently grim or washed-out backdrops; Final Fantasy VIII compensated for this by making the character models much more realistic (as part of the grounded philosophy), but many of the backdrops, especially in world map combat, are kind of ugly and bland. But Final Fantasy IX has learned all the lessons of its predecessors: the character models are detailed, but they integrate seamlessly into the richly-designed backdrops showcasing the world around them. The color palette, soft-edged models, and camera placement really serve to make the characters seem part of the world around them, and the theatrical sequence uses a lot of tricks like having characters leap into the audience (with both foregrounded and backgrounded setting elements) to sell the illusion. In Final Fantasy IX, towns feel livelier, buildings look lived-in, and characters feel appropriately fantastical in their settings. A dramatic improvement on games past.

After the opening sequence, the next several hours show similar promise. After gathering the party in the Evil Forest, our band of misfits must traverse the Ice Cavern, escape the evil Black Waltz, uncover a conspiracy in the quiet Village of Dali, escape the leader of the Black Waltz on an airship, and finally find a save haven in the bustling metropolis of Lindblum.

At which point, much of the air goes out of the game and the pacing becomes kind of a mess. But in order to talk about what goes wrong, we have to get into the nitty-gritty of why Final Fantasy IX really doesn’t work.

Final Fantasy IX Overcompensates

In Film Crit Hulk’s massive James Bond essay, a persistent refrain is “each James Bond movie is an overreaction to the last one,” and I tend to think that applies to pretty much every long-running franchise: Final Fantasy is no exception.

Final Fantasy VIII, as I’ve argued, made two very bold (and ultimately unpopular) decisions. The first and most obvious was the Junction system. Apparently everybody thought it was too fiddly and complicated—or at least hated all of Quistis’ endless tutorials (which, remember, were designed to be resented in-game, for better or worse)—and so Squaresoft jettisoned all but the most basic character customization mechanics for Final Fantasy IX.

The only thing you can control about your characters in Final Fantasy IX is their equipment and their active skills. There is one more level to this: much like the Final Fantasy Tactics games, characters learn skills by equipping items over time, so you can memorize skills by leaving sub-par items on your characters while you level them up, but that’s it. There’s no job system: Steiner can only learn Steiner’s skills with Steiner’s items; Zidane can only learn Zidane’s skills with Zidane’s items—all you can control is how fast you learn skills and when to use them. In practice, this boils down to choosing whether or not to use the weaker or stronger item, or moving skills around to ensure you are protected from certain status effects and can do more damage to certain enemy types.

This is especially egregious because you spend most of the game getting drip-fed items at irregular intervals. Much of the early game will be spent with only one or two options for each character’s item slot: once you’ve learned that skill, too bad! It’s not like you can equip anything else! When you get to a town you can buy more items, which is good, but the game offers significantly fewer opportunities to explore than either Final Fantasy VII or VIII did, and spends long stretches of time funneling you through the main plot, away from any store where you might buy new items. Worse still, stores have scripted inventories, which change as the game progresses—and many sell items that will be duplicated in the next dungeon, so you might well spend a ton of money buying an item (for fear the store will drop it later) only to find the same item in a chest or enemy loot a few minutes later. It’s simplistic, arbitrary, frustrating, and boring, all at the same time.

Plus, for fear of missing cool items, you’ll probably want to spend a lot of time using Steal with Zidane. Most bosses have good items to steal, so it’s worth spending his turn trying to get them if you can. Which means—surprise!—we’re right back to stalling bosses, just like in Final Fantasy VIII, only this time, there’s no guarantee that you’ll get the item you want: Steal works randomly (rather than the Draw system, which revealed the spell once you tried to draw it, and was pegged to your Magic stat), so power players get to see the “couldn’t steal” notification AGAIN and AGAIN and AGAIN as the game goes on. Then, you might very well get the item you want, only to find you’ve already learned to relevant skill, and let the silly thing languish unused for the rest of the game.

And just in case you thought we were done—oh no! You may be stalling bosses so you can steal the best items, but these items are not the game-breaking power base that we see in Final Fantasy VIII, so you can ALSO grind levels every time you find that your characters are underpowered. Which is virtually all the time. After you reach Lindblum, the party splits and you’ll end up forced to use certain characters at certain times, well into Disc 3. Sometimes Final Fantasy IX anticipates this (as when you get to power-level Steiner with Beatrix during the attack on Alexandria), but oftentimes it just gets ignored (as when, directly after power-leveling Steiner, you get stuck with the woefully underpowered Freya instead, who has also been missing for hours of the game). So you will spend hours grinding away through weak enemies, and stalling bosses for good items.

But wait, there’s more!

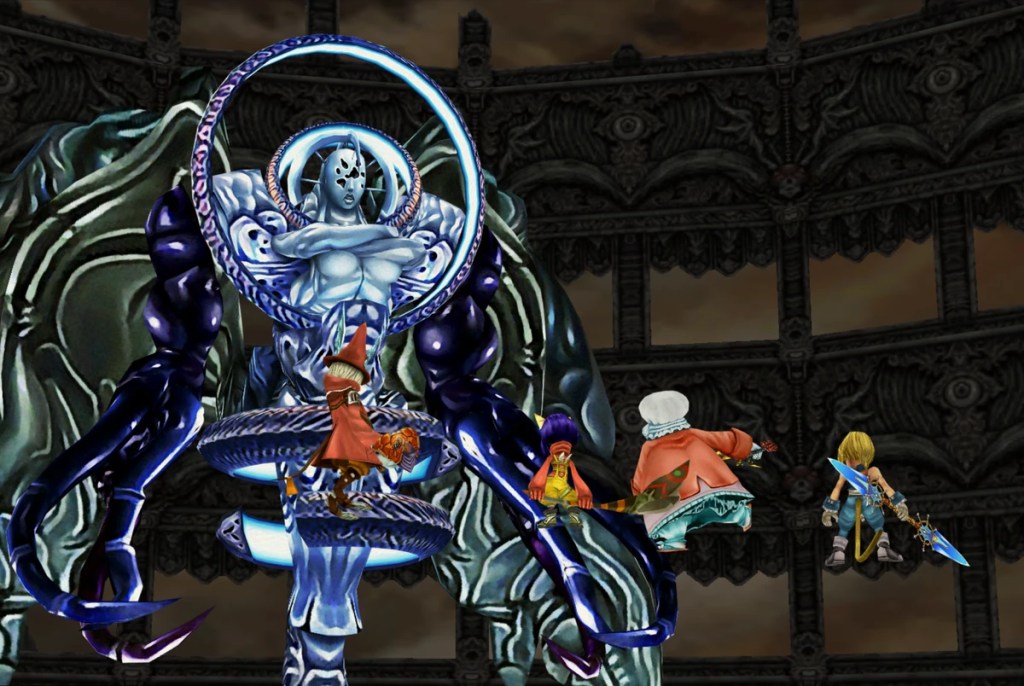

Remember that this is still the bigger, better sequel to Final Fantasy VIII, so we have to do something to outshine its battle system. And that is: we’re back to four characters in the party!

This itself isn’t a bad thing: from the very first game in the series, four-character battles were the standard: Final Fantasy VII was actually unusual by dropping the number to three, presumably for balance and processing concerns. But Final Fantasy IX increases the number of combatants to four and then doesn’t rebalance the combat.

I mean, maybe they did. I can’t be sure. But it sure doesn’t feel like it.

Most battles—even run-of-the-mill monster battles on the world map and in dungeons—will find you queuing up actions for your characters only to have the situation change dramatically while you wait for them to act. Since the attack animations (let alone summons and magic effects) still take a long time to play out, you’ll frequently have two or three characters waiting to act while your enemy finishes hitting you, and the game doesn’t bother to tell you when one of the other enemies had queued up ahead of you. In Final Fantasy VIII, this wasn’t a huge deal: it was rare that you had more than one character charging an action at any time, but with four combatants, you’ll set up a cure, only to have that character get killed before it triggers—or you’ll commit a healer to attack because it seems safe, only to have half the party wiped out before the attack actually goes off—or one of your characters will Limit Break (Trance, it’s called here), just in time for the battle to end and you don’t get to use it.

At least part of the problem, too, is that enemies have triggered actions that respond to being hit, some of which can jump the queue—and these attacks are often random, so you don’t know whether they’ll trigger or not in a given situation. And especially toward the endgame, many of these attacks will outright flatten or incapacitate a party member entirely, which makes it incredibly difficult to keep track of who’s acting, who still needs to act, who to heal and when—the whole combat system is a mess.

And, lest we forget, you still have very little control over your characters! In Final Fantasy VIII, if the game wasn’t playing fair, you could move some spells around and play just as unfairly in return. But in Final Fantasy IX, your pool of spells and abilities tends to be very narrow, so if you’re getting your butt kicked by a particular boss or random monster—tough cookies! Better leave the dungeon and go grind levels for an hour or two, then come back!

Ugh.

Somehow, despite all the risks in high-stakes combat Final Fantasy VIII encourages you to take, I find I die much less in that game than in Final Fantasy IX’s much more controlled combat environments. And much as you might criticize me for not being good enough at the game, I couldn’t help but feel like it was not fair. How could I have known that enemy would commit that action? How could I have compensated for that attack when my healer was already queued up to cast a healing spell, and got killed before it went off? In Final Fantasy VIII, my deaths tend to be the result of well-intentioned errors: I flew too close to the sun, and it’s my fault I got burned. But in Final Fantasy IX, I just sit there cursing at the screen, debating whether or not I want to take another crack at it.

No wonder I never got through this game before now.

Vintage Final Fantasy

I said that Final Fantasy VIII made two daring and controversial choices: the second was that same grounded-ness I keep banging on about, and which I liked so much about the game and its characters. It’s weird to think that grounding the game in reality—subtle human psychology, human decision-making, relatable characters—was a controversial or even “bold” choice, but that’s how it seemed to turn out. Final Fantasy VIII still feels radically different from the other games in the series because of those choices: still feels unlike any other video game, really.

Final Fantasy IX sprints in the opposite direction. Final Fantasy IX is a Final Fantasy game, through-and-through. If VII and VIII represent the biggest deviations from the original settings and tones of Final Fantasy past, IX is the return to form for the PlayStation era. We’re back to four party members, back to black mages with pointy hats and glowing yellow eyes, back to creative character models often removed from the simply human. We’re back to knights in armor, jumping lancers, airships, medieval villages, and castles, castles, castles.

And I’m honestly not upset about any of this. This is fine. If anything, it’s weird that it took until the third game on the Playstation for Squaresoft to say: “hey, let’s just do an original-style Final Fantasy game on fancy contemporary hardware” and then do it. They made their more daring games; they’ve earned a bye for a nostalgia-grab.

But…there is a lot of nostalgia on display here.

Past Final Fantasy games had allowed themselves a certain amount of liberties concerning references to earlier games, but there were some pretty hard lines. There’s always a character named Cid, and he’s usually connected to the airship. Biggs and Wedge might show up as soldiers in the enemy army. You can bet Chocobos will show up at some point. Recurring franchise-specific enemies like Tonberry and Cactuar will appear; other more generic enemies like Behemoth and Iron Giant will probably show up by the end of the game, too. Summons will be frequently re-used: Odin, Shiva, Ramuh, and Bahamut are all franchise mainstays. Likewise, certain weapons like Masamune and SaveTheQueen, or the Genji armor will be available.

But there are almost never overlapping locations, nations, political struggles, or characters. Yes, there will probably be some kind of militaristic empire to fight, but there’s no indication that the empire in IV is connected to the one in VI or VIII. Yes, you can go to the moon in several of these games, but the method is rarely consistent, and what you find there will differ from game to game. Yes, you will almost certainly get an airship for easy traversal, but there’s no connection between where those airships originate in each game.