So Magic the Gathering is doing an Assassin’s Creed set, my wife bought me some cards, and I have thoughts.

A Brief(ish) History of Magic and Me

You know the drill: long expository sections incoming while we talk about what brought me to this particular existential crisis.

I started playing Magic the Gathering in 1997. At the time, it was still a young game with rough edges. Fourth Edition had just standardized a bunch of the cards that were still janky in Unlimited, Tempest had just released with Stronghold on the way, advancing the story of Gerard Capashen as he sought out his nemesis, Volrath, and Portal had just released (conveniently for me) as an obvious entry-point for new players.

I fell in love with the game pretty much immediately. I loved the artwork and idea of telling stories through the cards, set-by-set and game-by-game (which was front-and-center to Stronghold), and I loved the creatively-designed locations, which changed from set-to-set. The overarching lore tells us that Magic players are “traveling across the planes in a wizard’s duel,” which allows for a curious combination of aesthetic exploration and creativity across genres and storytelling traditions (like the Arabian Nights set, or wintry Ice Age).

Most of all, I loved the strategy of deck-building, and I loved the thrill of watching an idea I’d brainstormed or a connection I’d see among disparate cards come together in a game, surprising my opponent and forcing them to react to the strange board state I’d created. I found friends to play and trade with, and it was probably my first experience with social gaming in a community, beyond sitting in front of a television playing MarioKart.

But fads change, Magic evolved, and over the course of my school career, I dropped in and out of Magic a few times. By 2000 (around the time of the Mercadian Masques block) roughly everyone had switched to the hot new Pokemon Trading Card Game, which I liked less, but I found myself unloading many of my old Magic cards so I could afford more Pokemon cards. By 2001 we were all playing Magic again, the Invasion set was riding high with more high-fantasy stories of Gerard and his crew, and I was kicking myself for giving up my old cards.

My interest waned again after Mirrodin released in 2003—the set was totally focused on artifacts, and I was predominantly a black player. After 2005, during my college years, I bought few new cards. By then I’d learned that it was easier to provide decks to other people for pick-up games than expect people to have their own. Magic became, to me, like a board game. I kept a handful of decks constructed and loaned them to people as the occasion demanded. This suited me (I enjoyed deckbuilding and finding strategies better than winning, and when everyone around was using one of my designs, I could more easily see the way these synergies and ideas worked off of one another), and I grew comfortable teaching others to play the game on the fly, often in pick-up groups of three-to-six people. I had virtually no interest in the competitive dimension of Magic, but had turned it into a way I could socialize with others over a thing I enjoyed.

Magic’s High Renaissance

After college, though, I came back to the game in a big way, and for three primary reasons.

First, while substitute teaching, I stumbled into our school’s Game Club, which had basically become an informal Magic venue. At the time, I was feeling pretty lousy—making little money, disconnected from my college friends, career at a standstill—and I desperately needed some kind of social outlet (which Magic had always provided).

Second, the Commander format had just started becoming popular. At this point, Magic had been around for well over fifteen years, and had accumulated a vast roster of cards with a wide variety of conflicting design priorities, so Magic’s owners (Wizards of the Coast) had begun defining different formats in order to cater to both long-time fans and new players. This began the trend of “Set Rotation”— restricting the competitive Standard format to the last several sets, changing every couple years to accommodate the new sets, while informally encouraging more storied play in other formats with less support and prestige.

This was a controversial, but necessary decision for the competitive state of the game (which was now big business in its own right – World-class competitions were becoming high profile events, and local hobby-store “Friday Night Magic” events were becoming ubiquitous and standardized as well), but it chafed long-time players. As Magic focused on attracting new players, and limiting its scope to recent releases, these veterans started experimenting with the basic rules of Magic, outside the Wizards-sanctioned Magic environment, to take advantage of its immense card library. One of those inventions was Commander (or EDH) – a new take on the game where players built massive 100-card decks (as opposed to the usual 60), with the rules that a deck must:

- Include one legendary creature (Commander) who you could play at any time from a separate “Command Zone” without drawing it from the deck.

- Include no more than one of each card (other than basic lands)

- Only include cards of your Commander’s colors

This was absolutely a deckbuilder’s format. I no longer had to seek out and accumulate multiple copies of high-power (and expensive) cards, which flattened a deck’s strategies, but could use whatever cards I had lying around, accumulated over decades of play. Having one card readily available at all times meant I could exploit creative synergies in whole new ways, and the color restriction meant it was useful to trot out unusual multicolor cards which were otherwise difficult to employ in a standard 60-card deck. It was Magic I had always loved it: creative, experimental, and geared to slow, social play rather than quick, competitive sessions.

My first experiment featured Tsabo Tavoc as my Commander (in my usual dark, black-centric playstyle), and was a rousing success.

But not long after my first, informal experiment with the format, Magic released the first official Commander decks for sale. Picking up on the frustration of their long-term players, they had been occasionally releasing fan-favorite format experiments like Planechase and Archenemy over the last several years, and tried Commander with a release of five color-themed decks spanning the history of Magic, and introducing new cards (like Command Tower) which supported and expanded the possibilities of the format.

It went off like gangbusters. The pre-constructed decks were immediate classics (I ended up buying three of the five; all are now ridiculously expensive to obtain, and many of the unique, new cards are now very valuable), and Commander gradually became a bigger and bigger part of the gaming scene.

Third, something was just in the air at Wizards in those days: they had rousing success with their set releases for several years in a row: the strange, land-based mechanics and high-profile Planeswalkers of Zendikar gave way to the reintroduction of story-based foes from sets past in Scars of Mirrodin, followed immediately by their foray into gothic-horror with Innistrad. These sets were all amazing: a return to the strong narratives of yesteryear (both in spirit and in fact), with strong, unique aesthetics and dynamic mechanical innovations (SoM’s “infect” and “proliferate” mechanics remain powerful, but largely not overpowered, tools to this day; Innistrad’s introduction of double-sided cards—originally designed to simulate werewolf transformations— have been iterated on in fascinating ways for years to come).

But experimentation also comes at a cost. Some cards proved too powerful for the game’s balance (most notably, the mighty-and-fallen Jace, the Mind Sculptor), and as Commander became more popular and standardized, more cards had to be banned from the format to avoid breaking its balance (such as Emrakul, the Aeons Torn or Recurring Nightmare – which I’m still salty about). Once again, old-school fans started chafing against these decisions, which prompted Wizards to introduce the “Modern” format—a compromise that excluded really old sets with wildly different design sensibilities, while incorporating and encouraging collectors to show off any card released since a fixed cut-off date in the 2000’s. This also allowed Wizards to also re-release older cards to re-introduce them to the format (and get other players to buy more packs).

Wait—did you just see a capitalism run by here? Probably just my imagination.

The Corporate Years

If the time between Zendikar and Innistrad represents a high-water mark in the history of Magic the Gathering (the “silver age”, maybe?), it was, like all good things, doomed to end. Return to Ravnica was a good block with good ideas, but the third set in the series, Dragon’s Maze, is almost universally reviled. Theros, released in fall 2013, was well-remembered, but I don’t think it sold especially well. The empire was in decline. I kind of regret not getting into that set, but I had some kind of irrational distaste for it at that point (and little disposable income). I tried Khans of Tarkir the next year, but didn’t get much out of it, and preferred to rely on the decks I’d built in the past than try to keep up with these lackluster sets. I still loved the game, still loved building decks, and especially loved the endless re-combinations of my existing library of cards made possible by Commander, but I had no interest in keeping up with the new sets or buying new packs.

Instead, between 2016 and 2020, I found myself playing a lot of online Magic. Magic had tried pivoting to a video game format several times in its history. But Magic Online was expensive and unrewarding, and the Duels of the Planeswalkers games, though fun, were very limited in scope, excluding many of my favorite cards. Magic Duels was a more robust effort, and I found myself playing it a lot in my test-grading years, since I could grade and play a session of Duels online at the same time (I was not good at that job…). Magic Arena, released a couple of years later, was even better, having learned from the errors of Duels.

But throughout this period, keeping up with the mechanics of Magic’s Set Rotation was a mess. After Khans, Wizards abandoned the now-decades old three-set release format, with a big new location-defining set each fall, and two follow-up expansions in the winter and spring. The new set-rotation scheme was meant to be faster, looser: presumably so they could spring back faster from a bad release. Additionally, they were balancing a dozen different formats (Standard, Extended, Modern, Legacy, Draft, Commander) across both in-person and online play, and each release was accompanied by bans, restrictions, and complications that just frustrated the whole community. I liked some of the new releases (like the return to the Innistrad location in Shadows Over Innistrad in 2016)—and even occasionally bought cards after fooling around with them on Arena, but after playing the market (and finding it distasteful), I didn’t much care to buy boosters and sit for tournaments. Instead, I preferred to buy single cards from the aftermarket to realize my grand deck designs.

But with the move away from the three-set release format, all the aesthetic depth was also on the chopping block. What made something like Innistrad so compelling was the way the location was developed. The first set established the basic mechanics of the gothic-horror setting: angels, demons, zombies, vampires, werewolves, ghosts, mad scientists, and the humans just trying to get by, but the second and third expanded on the setting, iterating on the idea in new ways. Dark Ascension (the second set in the series) had a “fateful hour” mechanic that only triggered at low life, driving home the idea that this was a last-ditch resistance to apocalyptic darkness; while final installment Avacyn Restored abolished many of the earlier death-and-doom-based mechanics in favor of “miracle” cards that could be played unexpectedly, reversing the drift of play. Now, sets would only be explored once (like Dominaria in 2018, a throwback to my earliest days playing Magic), or twice (like Ixalan the year before, the community-favorite pirate setting), with maybe a revisit promised in future sets down the road.

But Wizards was also releasing new sets at an unprecedented rate. Yes, there were still only three or four big new set releases each year, but these were punctuated by dozens of smaller releases across the year—new Commander decks, Modern-specific re-release sets, promotional experiments, and what have you. Occasionally I’d pick up a pre-constructed Commander deck if it suited my fancy, but only rarely, and only when I had money to spare.

A Guest in Magic Dystopia

In 2021, I made my final foray back into the game. A friend invited me to join him for a weekly budget-Commander tournament, and the timing coincided with the release of Innistrad: Midnight Hunt, a return to my favorite setting with a schlock-horror-movie aesthetic that I was pretty down for. I regretted missing most of Shadows Over Innstrad, and I was still lonely after the year in lockdown, so I took him up on it.

What I found was kind of horrifying. The players were nice enough, but while Commander had always accommodated the slower, more creative playstyle, many of these players were fiercely competitive and their decks were well-oiled machines of unstoppable and complete domination, using decks that had been identified and entrenched for years as dominating strategies. On the one hand, that meant cards I’d had in my library for years (like Rhystic Study or Isochron Scepter) had become wildly valuable; on the other, I was immediately outclassed by their familiarity with recent releases, and I spent many a game sitting and waiting, turn-after-turn, to lose.

Part of the change was the development of an enormous online competitive community. Magic had always had a community of players advising others about the game, but now it had turned into an entire industry: YouTubers and bloggers frenetically talking about each new set that was released, speculating about the changes to the game’s competitive state, and releasing their own decklists for followers to emulate and iterate upon. Magic cards had become a vector for investment—new releases would be bought up by the boxload, with players hoarding cards for later sale—often turning a profit and building a viciously competitive deck at the same time.

And Wizards? In 2021 alone, Wizards released:

- Kaldheim – a brand-new set with a Norse vibe

- Kaldheim Commander – two 100-card preconstructed decks with new card releases

- Time Spiral Remastered – a return to the Time Spiral set which served as an opportunity to re-introduce old cards to the Modern format

- Strixhaven – a brand-new set riffing on the Harry Potter “school of wizardry” idea

- Strixhaven Commander – five 100-card preconstructed decks

- Modern Horizons 2 – another Modern format re-release opportunity

- Dungeons & Dragons: Adventures in the Forgotten Realms – (remember this: it will be important later)

- Innistrad Midnight Hunt – the main reason I was showing up

- Innistrad Midnight Hunt Commander – two more Commander decks (I own both)

This was…overwhelming. I was happy to ignore most of what was going on in favor of playing my cheaply-constructed Commander deck from my already-owned cards, but when people started making suggestions or recommendations from recent sets, or started casually talking about how Midnight Hunt or sequel Crimson Vow might affect the meta (before these sets were even released!), or complained about the flurry of recent bans (Oko, Thief of Crowns was the high-profile example, but there were more to come in the next months), the whole thing seemed distastefully corporate.

Even opening boosters had become more complicated: Midnight Hunt was divided between 11-card “Set Boosters” which were cheaper, and more regularly included promotional, alternative-art cards, “Draft Boosters,” the usual 15-card option, now designed for drafts, rather than incidentally used for them, and “Collector Boosters,” which were easily three times as expensive as Set Boosters, and were guaranteed to include all kinds of fancy promotional cards, foil cards, and ultra-rare printings.

I played my games, even made it to fourth place for the final match (which I lost, badly), but left feeling kind of gross about the whole thing. I got plenty of cards from the new sets, which I used to build my Innistrad Cube (the apotheosis of deckbuilding—basically I designed my own Innistrad-themed Magic set for drafting purposes), and felt pretty comfortable walking away without a second look.

The community consensus was that Midnight Hunt and Crimson Vow were overwhelmingly weak, poorly-designed sets, bouncing back from the power creep evident in Throne of Eldraine and Khaldheim.

After my tournament experience, I designed a couple more decks, bought a few cards to build them, but I was comfortable being done with Magic for good and all.

No really. This time I was really done.

…

What?

Horror Intensifies…

Remember how I said we’d come back around to that Dungeons and Dragons set? Let’s do that.

Way back in 1997, unbeknownst to middle-school me, Wizards of the Coast (which originally published Magic the Gathering) had acquired Dungeons and Dragons—every book, miniature, etc., published under the license since 3rd edition has gone through Wizards. And since Magic is pretty fluid about hopping across planes and settings (as D&D is), in 2021 Wizards decided to release a D&D-themed Magic set (following up on their release of Magic-themed D&D books in years prior). There were some fun mechanical innovations (others, like “entering the dungeon” were rather cumbersome), but it passed largely without seriously influencing the state of the game.

Since then, though, the gloves have come off.

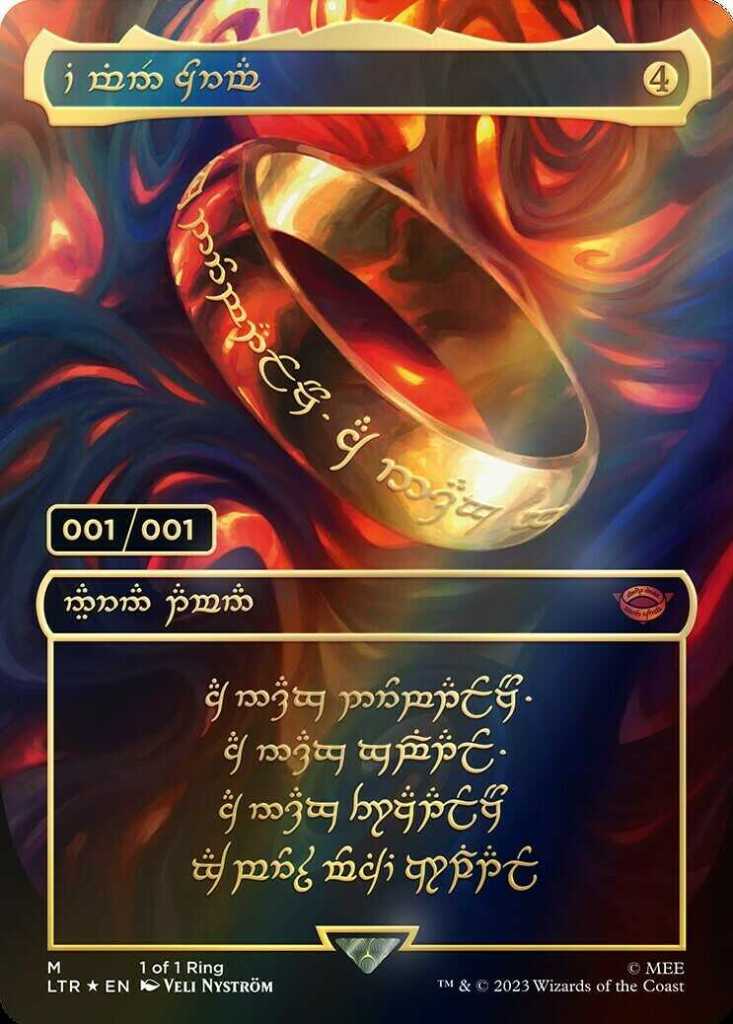

Each year since, Wizards has released at least one set which crosses Magic with another established intellectual property in the fantasy/science-fiction domain. In 2022, they released a Warhammer-themed set (as well as Baldur’s Gate-themed Commander decks). In 2023 they released (and thoroughly hyped) two Lord of the Rings-themed sets, as well as Doctor Who-themed Commander Decks. The Lord of the Rings set included a one-off printing of “The One Ring” in the dark speech of Mordor, which somebody did pull and is apparently valued at some utterly outrageous price.

And I HATED it. Hated it with a burning passion.

And, look, I get it. Corporations gonna Capitalism. It’s a thing. Wizards is apparently making money hand over fist with these crossover releases, but I want absolutely no part of it. Not just because I think it’s crass (Tolkien spins in his grave at the thought of a Tom Bombadil card), but because it’s absolutely leaning in to everything I dislike about the current state of Magic: the limited releases, the speculation and aftermarket communities, the indifference to aesthetic consistency and creativity, the compulsion among power players to keep up with every new release, the indifference to quality control and over-use of banning/restriction to correct game balance oversights, the multiplication of formats—all of this is made worse by these decisions, and it’s not a clear-cut financial win either, if the past years’ slump in card value is any indication (market saturation, anyone?). The game is almost certainly made worse overall by these choices, but the short-term profit is evidently more important than the brand’s endurance.

But this is all an old song by now, right? Old-school Magic players (like myself) have built their own cottage industry around complaining about Magic’s bad decisions. You don’t need me to tell you that the game is circling the drain.

Good, because that’s not the end of this story.

In fact, it’s only the beginning.

2024 continued Magic’s dalliance with other franchises. March saw the release of a Fallout-themed set, which was apparently bought up almost immediately—my Fallout-loving Commander partner sheds a tear. And this past week (July 5, 2024) saw the release of an Assassin’s Creed-themed set.

And, in many ways, I consider this the absolute nadir of Magic’s corporate era. There is something very appropriate about Magic—a game full of great ideas and history that has gradually sold itself out for the sake of short-term gains at the expense of long-term endurance—partnering with Assassin’s Creed—practically the poster-child of long-running video game franchises that have devolved from good ideas to corporate-committee-designed yearly-release pablum. This is Magic’s Dante-esque punishment, the tier of corporate hell where pandering brand-indifferent publishers all get together and fornicate with one another in forced rounds of mutual exploitation. I was horrified and disgusted at this partnership, and also felt the schadenfreude of seeing the vicious brought low.

I was also…intrigued…?

An Aside About Assassin’s Creed

So I’ve talked about Assassin’s Creed…a lot. More than is probably appropriate. Possibly ad nauseum. And my thoughts are pretty well-articulated elsewhere. But let’s recap, briefly, so we can all be on the same page without listening to me rant for six hours.

- I kind of love the first Assassin’s Creed game, for all its faults.

- I absolutely love the idea of a video game that lets you putter about in meticulously-rendered historical places and times, and I have a laundry list of places I’d like the franchise to visit at some point.

- In general, the franchise fails to live up to these expectations, and is in fact infamously guilty of rushed, poorly-conceived game design and the worst excesses of corporate culture.

- I want better, and while I’ve given up on expecting it (and haven’t played any of the games since Unity), I still watch the franchise periodically for interesting releases or changes.

- That, and my students keep telling me I have to play Odyssey – the one that takes place in Ancient Greece.

Cool? Cool.

Now we’re all up to speed, let’s start this story proper.

An (Unwelcome?) Unexpected Gift

On July 5th, 2024, my wife left a box outside my office before taking her afternoon nap.

Apparently, back in April or May, she discovered that Magic was releasing an Assassin’s Creed set (including a SOCRATES MAGIC CARD), and decided to buy it for me. She did not know at the time (because she is a normal non-Magic-playing human being) that the decks she bought for me did not include this Socrates card.

I opened this box, discovered the contents, and had a think.

Thought #1:

That was so sweet! I love my wife!

Or at least that’s my story and I’m sticking to it. More relevantly:

Thought #2:

Shit. Do I want this? Do I want to tacitly endorse Magic’s continued descent into corporate bullshit by opening this box and adding it to my collection? Maybe I should just return it on the sly, and never bring it up again.

Thought #3:

I want this. This is cool. It’s pre-constructed decks, like I used to buy in the old days. This can be a one-off, totally separate thing. I am not compromising my morals here. I just won’t buy any more. And I can be a gracious gift-receiver. We can live with this.

Thought #4: (after some cursory Internet searching for the decklists)

Wait. There’s an Ezio card? That’s cool. And there’s a little baby Ezio card? That’s also cool. And there’s a mechanic where you can summon Assassins cheaper if you deal damage with an Assassin? Like Ninjitsu? That’s super cool. And the deck is blue-black? I love blue-black decks! Wait—most of the coolest assassins are blue-black! And they’re all legendary? So they could be Commanders?

…etc., etc.

Thought #5:

No. Absolutely not. We are not getting back into Magic—it’s too expensive, we have no money, and I DEFINITELY do not want to support these crappy cash-grab licensing things. Remember the Lord of the Rings set? We CANNOT endorse—

Thought #6:

THERE’S A SOCRATES CARD? AND HE BLOCKS DAMAGE BY ENGAGING THE MONSTERS IN DIALOGUE! HOLY FRIGGING SHIT! I NEED THIS.

Within five days, I bought a “Bundle” (it contains nine seven-card [wtf!?] boosters, and fun accessories like a die, lands, etc.), ordered several dozen individual cards online, and have designed not one, but three new decks around the new cards (one of which features Socrates as a commander, because I think that’s hilarious and dumb and wonderful).

Rough estimate of expenses: $150, not counting the initial gift my wife got for me.

As I wait for my cards to arrive, I find myself reflecting on all this. Because I don’t generally consider myself to be an easy mark for cynical nostalgia cash-grabs, or transparent corporate cross-overs, or any of the obvious, pandering, commercial nonsense that a Magic/Assassin’s Creed crossover represents.

In short: I don’t want some corporation telling me what to like, and I definitely don’t want to be the guy who likes what he’s told to like.

Concerning Brand Loyalty

This is something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately.

A friend of mine recently invited me to the Final Fantasy: Distant Worlds concert at Carnegie Hall. It was my first time in the venue, and my first time hearing a full orchestra live. We got to hear Uematsu’s orchestral composition of Dancing Mad from Final Fantasy VI with a full chorus and pipe organ, and live renditions of Liberi Fatali and One Winged Angel. Masayoshi Soken, lead composer for Final Fantasy XIV and XVI was present, hanging out in the audience, waving excitedly when the conductor pointed him out. All very exciting stuff.

But much as I enjoyed the music, the venue, and the crowd’s enthusiasm, I was also very struck by the commitment to the brand. At one point, Soken stood up and, through an interpreter, joked that he knew we’d all beaten Final Fantasy XVI, but we had to hurry up and get through the Elden Ring expansion so we’d be ready for the new addition to Final Fantasy XIV coming up (to almost universal applause and laughter). Many of the most touted performances of the afternoon were directly from Final Fantasy XVI—and the conductor was quick to tell us that this was the first time they’d been performed at the orchestra concert.

And, look – the music was good. Really good. They even had soloist Amanda Achen sing with the chorus and the orchestra.

But it left me a bit cold.

I haven’t played a Final Fantasy game more recent than XIII-2—which I liked well enough, but the XIII legacy is a bit weird, and even die-hard Final Fantasy fans consider it a low point for the series. XIV is an MMO, and I’m reluctant to shell out subscription fees ON TOP of a $60 price tag for the expansions, and I only last year acquired a PS4, so I haven’t even played XV yet, much less XVI. As a veteran of the old guard, with little interest in or experience with the new games, it became especially obvious to me that I was out-of-step with the rest of the concert crowd.

My friend was familiar with the whole history of Final Fantasy music: he loved every minute. The crowd skewed young: their enthusiasm was high for new music from XIV and XVI, but pretty cool toward the throwbacks from Final Fantasy VI (which I enjoyed the most). Meanwhile, unfamiliar with the new music, I found myself just trying to appreciate them aesthetically, which I did, well enough, but…it wasn’t the same?

This ties into a much more complicated conversation about music—how the technical limitations of the SNES and early hardware contributed to melody-heavy music and memorable themes, while later games can accommodate fully-orchestrated soundtracks (which conform with contemporary melody-less musical standards). And I think there is a case to be made for the style being fairly alienating to me (probably my favorite of the unfamiliar performances was another simple, theme-heavy XV track which I liked better than many of the soaring, busy compositions from key story beats in XIV and XVI). But the question I left with was the simpler one:

Was I just interested in the nostalgia of it all?

I liked being able to anticipate each beat in a song I’ve heard a thousand times (like Dancing Mad), and that joy was compounded by the live performance. But between the crowd’s diminished enthusiasm and the fact that the orchestra struggled to keep up with a piece that was, admittedly, never designed for human performance, I couldn’t shake the fact that this was not good music, and was only firing the pleasure centers of memory, not pure aesthetic enjoyment. It was still a rush, I still enjoyed it, and I still think it was the highlight of the concert for me, but I’m left wondering why.

Why were all those people willing to spend that much money, that much time, on a franchise I hadn’t prioritized in years?

Why wasn’t I?

Why do I like the things I like? Dislike the things I don’t? Is this a matter of taste, or purely of some corporation sinking its hooks into a younger, more impressionable me, until I can’t tell the difference between what is good and what is familiar?

Is there even a difference between these things?

In short: Can I trust my own taste?

Really Hoping I Didn’t Sell My Soul To Ubisoft Right Now

Because, guys, I know Assassin’s Creed is trash. And I know Magic has become trash. But I can’t help getting excited at this particular confluence of trash, and apparently spending quite a bit of money on it. Which leads me to one of two conclusions.

(1) Either I’m a corporate stooge, programmed to like certain things by years of experience and connections to happier times.

-or-

(2) There’s something much more interesting (and possibly much more complicated) going on here

You’ve probably figured out at this point that I’m leaning toward (2), or this wouldn’t be a massive personal essay, but just me rocking back and forth in a shower stall wondering if there’s an “Assassin’s Creed Anonymous” out there. But you may also be suspicious of my motives at this point. (I sure am.) So let me present the case against (1).

- I haven’t bought Magic cards in years. Presumably, if I was just a Magic stooge, I’d have kept up with all the new sets coming out. The whole Rise of the Machines event looked pretty cool, tapped into many of the same mechanical/storytelling impulses I tend to like, and yet I didn’t buy a single card. Nor did I buy into the cyberpunk Kamigawa expansion, or the fantasy-noir Streets of New Capenna, despite those being obvious genre interests of mine.

- I haven’t bought into any Magic crossovers before this one. If it wasn’t obvious, I found the Lord of the Rings Magic set downright repugnant, despite my love for the franchise. I like Doctor Who and Fallout as distinct franchises well enough, though I’ve never been a huge fan of either—and still didn’t buy cards from either set. Even when they did in-set crossovers (like alternate-art versions of Crimson Vow cards featuring characters from the original Dracula), I tended to buy the vanilla Magic-themed versions of those characters when deckbuilding (though that could just be ressentiment: they were rare and expensive).

- I haven’t bought a new Assassin’s Creed game in years. Technically, I have bought most of the newer games—but only on sale, after they’ve been out at least a year. I haven’t pre-ordered or played an Assassin’s Creed game newer than Unity. I mean to, but I’m not terribly enthusiastic about it (mostly because I’ll have to record footage for my video series, which is tiresome).

All that to say, I’m not a stooge for these brands or companies. I don’t give them money just because they’ve released a new product—I don’t care about 99% of the things they release.

But, you may well counter, you do care. You have a whole video series on Assassin’s Creed, just wrote something like ten pages on your history with Magic. Clearly you are invested, and perhaps you just miss these things. You’re still motivated by your loyalty, but you’re just experiencing the same cycles you’ve experienced since you first fell off Magic back in the 2000 Pokemon debacle!

Very astute and insightful, imaginary interlocutor. You’ve paid attention well.

But now we’re getting into those same “more complicated” possibilities I mentioned earlier. So that requires a new section heading.

A New Section Heading

I won’t deny that I apparently appreciate Magic in cycles. Nor will I deny that this probably informs my decision to get into the game now. (Coolly designing one deck and buying it is a controlled re-entry into the habit; frenetically designing five new Commander decks in two days represents some kind of suppressed desire/frustration.)

So let’s call this The Cyclical Stooge Hypothesis. I.e., I’m not rushing out to buy every new set, but after, say, every three years or so, I suffer some kind of Magic-withdrawal, and have to come crawling back to the game for all the same corporate-hooks-nostalgia reasons that inform perpetual/habitual Magic players. If true, this would reflect poorly on me (it’s not taste, it’s addiction), but only insofar as I’m sick and relapsed.

But I think there are some problems with—or at least clarifications to make about—The Cyclical Stooge Hypothesis. For one, the cycle is degenerating. Each successive cycle of Magic-buying tends to be more deliberate, more controlled, and less expensive. In the Innistrad years, I bought multiple booster boxes and acquired thousands of cards. Now I’m buying one box, and a handful of singles, in the interest of building one deck. Even my dalliance with Crimson Vow in 2021 was ostensibly for the purpose of building my Innistrad cube, which is now finished, and which I haven’t tinkered with since. (Nor do I intend to.)

Second, while this hypothesis would explain why I’ve come back to Magic, it doesn’t explain why it happened now. The relapse could theoretically occur at any time. My wife buying cards for me seems like an obvious trigger, but somewhere between Thought #1 and Thought #6, I presumably could have ducked out of it, and didn’t. Somewhere between opening my gift decks and buying $150 worth of cards I could have either stopped myself, or given in and spent another $150. You might well argue that this is rationalization—in the sense of justifying behavior with reason after the fact, but I would stress that this is, in fact, rationalization—in the sense of using reason to temper and control whatever stooge-like desire threatened to overwhelm my rationality. Whatever happened over the last week, it was a fusion of impulse and reason, not merely one or the other alone.

Third, this entirely leaves out the issue of Why Assassin’s Creed specifically? You could double-down and point to my history with the franchise, postulate a Double Cyclical Stooge Hypothesis, but I don’t think it would be terribly informative. The cyclical pattern underlying The Cyclical Stooge Hypothesis operates according to a pretty predictable factor: I rejoin Magic when there is a set I like (i.e., Zendikar, every Innistrad release) and leave when I dislike the set (i.e., Mirrodin, Theros, whatever was going on with the 2021/22 release madness). Which means that The Cyclical Stooge Hypothesis assumes that I Like The Assassin’s Creed Magic set, which means we actually haven’t solved the overarching problem of taste at all. Whether or not I’m a sucker for Magic doesn’t mean I’m incapable of discerning between a good and bad set within Magic. And the fundamental problem here is that Universes Beyond: Assassin’s Creed has every hallmark of being a bad set.

So let’s talk about why I like the Assassin’s Creed set.

Why I Like the Assassin’s Creed Set

Well, there’s a Socrates card.

-essay ends abruptly-

But no, seriously, I really love that there’s a Socrates card.

It’s also crap. It’s worth forty cents. It would not have been a huge investment to just buy that card. Nobody thinks he’s going to be competitive.

Why?

Because he’s silly.

Whether or not you understand the basic mechanics of Magic (which I don’t intend to explain here in any more detail than I have already, lucky for you), it should be pretty obvious what he does.

He talks to people.

Imagine some massive nightmare monster like Phyrexian Dreadnought barreling toward you, ready to deal a whopping twelve damage, and then Socrates just—patiently takes him aside and talks to him about the nature of good and the meaning of existence, and the nightmare monster Phyrexian Dreadnought politely nods his head and says “you’re right, Socrates—it is better that I do not devour the bodies of the living as a means of bringing about my own existence, but now that I am here, I vow to direct my boundless destructive potential to the cause of learning”—and both players draw six cards in the afterglow of mutually-beneficial intellectual debate.

This. This is what I want to happen in an actual game of Magic.

This is an aesthetically-appropriate, mechanical rendition of what Socrates, the man himself, would actually do. It’s silly and overblown, campy, and I am all about it.

But I also didn’t spend $150 on my Socrates deck.

I spent forty cents (plus shipping) on my Socrates deck.

(i.e., I bought a Socrates card, and built the remainder of the deck entirely out of my own pre-existing collection)

Then what did I spend the other ~$146.40 on?

Assassins.

See, when I design a deck, it usually happens in the following stages.

- Inspiration – I see a particular card (like Socrates), and I say to myself – “that’s really cool; how could I use/exploit/draw out synergies from this card.” Or maybe I see somebody else exploit a combo or synergy and say to myself “I can improve on this”.

- Brainstorm – I find cards that augment the idea. Can I find cards that force a player to attack me so I can get Socrates to debate them? What cards do I need to protect myself in the meantime? What do I do with the cards I draw? Often times, if this involves a specific mechanic, I’ll search for other cards with the same (or related) mechanic. In this case, I just rummaged through all the cards I own that could go in the deck, and then weeded them down to the 100-card minimum, according to what I thought most useful (or, in some cases, hilarious).

- Playtest – Ideally, once I’ve got a working deck, I play a few dummy games against my other decks to see how it plays, usually online, so I can experiment with cards I don’t own. Does it need more land? More counterspells? More offense/defense? I tinker until it feels just right—sometimes endlessly.

- Purchase – Once I’ve gotten the deck where I want it, I buy any cards I need and don’t own.

This works for me. It’s a cheap and streamlined process. Most players I know do something similar (although they usually skip over the first two stages by looking for existing deck archetypes; where I think all the fun is in those two stages).

But like I said, I didn’t purchase any cards for my Socrates deck, besides Socrates.

Commander Ezio

Poking through the set list for the Assassin’s Creed set, my attention immediately alighted on Ezio Auditore da Firenze, almost certainly one of the premiere cards of the set, and one of the most expensive/rarest.

Ezio is one of those fascinating commanders who *technically* counts as being all five colors, because he has an ability that uses all five colors in his rule text. Which means that you can build a deck around Ezio that includes any card in the history of Magic.

These tend to be pretty popular Commander options as a rule, and yet I don’t own any of them. The only five-color Commander deck I’ve ever built was a Sliver deck, and that’s, well, different.

But Ezio also doesn’t play like a five-color Commander. He can be summoned for black mana alone (remember—I predominantly play black decks), and also allows you to cast any other Assassin for two black mana (under certain conditions).

Meaning: he’s powerful, he’s fast, and he enables you to play many different-colored assassin cards without necessarily having a lot of different-colored mana.

Which is especially convenient, seeing as he was released in a set that is utterly filled with Assassins, all of whom are drawn from the Assassin’s Creed video games in some way.

And as I looked through the set list, the number of synergies began to multiply.

Here’s an Assassin that lets you put other cards in your discard pile (graveyard) quickly, and here’s an Assassin that lets you put Assassins from your graveyard onto the battlefield.

Here’s an Assassin that makes all Assassins more powerful.

Here’s an Assassin that gets more powerful for every Assassin you play.

Here’s an Assassin that turns all creatures into Assassins, and here’s an Assassin that can create non-Assassin token creatures.

Looking over the set, I felt a kind of cascading inspiration—connections and synergies compounding endlessly with every new card I looked at. I imagined how each new addition could change the board state, how new combinations and recombinations became possible, and how I might be able to tie those to other cards I already owned, or other mechanics I already played.

Some of this is just personal: I love blue-black graveyard-manipulation combo decks, and the set has a ton of blue-black graveyard-manipulation support. But it’s also more than that. It’s how the mechanics communicate ideas. And I’m more excited about these mechanics than I have been for a new Magic set in years.

Mechanical Expression

Magic at its best devises interesting and powerful mechanical expressions for the world it tries to depict. Take, for example, the Golgari guild of the city-plane Ravnica. The Golgari are sewer-dwellers, responsible for disposing of the city’s waste, but they are engaged in the same struggles for power and control that define the whole city. So in the first Ravnica block, they have a unique mechanic called “Dredge”, which allows you to take cards from your discard pile and put them into your hand, at the cost of discarding more cards from the top of your deck, potentially putting more tools at your (forgive the pun) disposal.

This evocatively expresses the idea that they are both wasteful and ingenious, using the trash of others to augment their own power, even as they risk overextending themselves (and your deck). They will gladly kill or sacrifice their own if it means benefiting the whole, and many of their cards feature fungus or mushrooms in the art to express this idea of unfettered growth from corruption and death.

It’s one of my favorite mechanics in the whole history of Magic, and I employ it often.

At this point you may have questions about my mental well-being, but we’ll leave that for now.

The Assassin’s Creed set has a similar mechanic of death-and-rebirth, but it’s framed very differently, and, consequently, ends up expressing some really interesting ideas from the video game franchise.

As you might expect, there is a card called “The Animus.” In the games, the Animus is the mysterious device which allows living people (like Desmond Miles) to access their “genetic memories” and relive the experiences of their ancestors. Over the first few games, Desmond uses the Animus to experience the life of Altair—an historical Assassin meddling in the affairs of the third crusade, Ezio—a Renaissance youth who dons the assassin’s cloak to exact vengeance for his father’s unjust death, and Ratonhnhaké:ton—a Native American who must examine his loyalties and allegiances during the American Revolution.

The Magic card “The Animus” allows a player to turn a creature in play into one in the graveyard—much like Desmond accessing his dead ancestors’ memories and abilities in the video game. The card representing Desmond himself grows more powerful with each Assassin in play and in the graveyard, representing his own growth as he accesses more and more of his connections and ancestral memories.

So, where the graveyard represents the sewers of Ravnica for the Golgari, here it represents history and memory itself—the mechanics have been reinterpreted, abstracted into a coherent surrogate for the rules and mechanics of the video game. It’s not a one-to-one translation, but it’s an effective way to communicate surprising depth from one medium to another.

OK, But That’s Not New

But at this point you might well point out: this is not new. This is what all the crossover sets do.

And you are right.

But let’s do some comparison, shall we? Let’s take a look at The One Ring again, though this time in English.

So. It’s Indestructible. (Makes sense. Gimli tries to destroy it and fails in the movie.) Though, obviously, this feels a little odd, since the whole point of the Quest is to destroy the Ring by casting it into Mount Doom. But that’s OK, because there’s a specific “Mount Doom” card, where you can “sacrifice a legendary artifact” (like The One Ring) and destroy a bunch of creatures (?).

When you cast The One Ring, you gain protection from everything. Cool. That makes sense. When Frodo puts on the ring, he becomes invisible—but also more vulnerable to spiritual forces like the Ringwraiths? So that’s not completely at peace with The Lord of the Rings, but it’s an approximation, I guess.

You lose life for using The One Ring—which also tracks. There’s that vulnerability we mentioned earlier. But there’s a specific “burden counter”, apparently, which we have to use to keep track of how heavy the Ring feels and how much damage it does to us when we use it. Ungainly, but effective. It definitely communicates that risk/reward quality of using the Ring.

But you can use the Ring to…draw cards?

I mean, OK. That’s…a reach. Drawing cards in Magic usually represents gaining knowledge or wisdom, but we can extend that to gaining power/control the way that Sauron does.

But where’s the rest? Where’s the ability to control other rings? Where’s the temptation of the ring?

Apparently, somewhere else:

Many cards in the set instruct the player: “The Ring tempts you,” which apparently advances a theoretical, non-The One Ring global effect as indicated on this little token card above. Apparently the first time it happens you have to select a Ringbearer from your creatures, and he gets all the abilities that have been activated so far. But you don’t “lose” the ring. It’s not like only one person gets the benefit, and then if you kill a Ringbearer you get to control the ring for the rest of the game.

This is…cumbersome at best. Painfully inaccurate at worst. It gets at some of the flavor and mechanisms of The Lord of the Rings, but ignores other, arguably more important ideas.

The Tolkien fans grumpy about the implementation of the Magic Lord of the Rings mechanics are legion. (Or at least as legion as there is an intersection between the two properties.) Everyone is frustrated by the way these mechanics work (or don’t work).

But that’s subjective! You may argue. There’s plenty about the Assassin’s Creed mechanics that are equally-fuzzy and underbaked. The only reason you get mad at the Lord of the Rings mechanics is because you are scrutinizing them too closely.

Yes. Exactly that.

The Advantages of Being Trash

The Lord of the Rings, for me and for many fans, is a story. An excellent story, well-written and rich with meaning, subtext, and care. And we love it as a consequence.

You could make the argument that the world of Middle-Earth was designed to be more than that, by Tolkien himself, even, and you would be right about that, too. But there is something beautifully, wonderfully finite about that world. It is made up of the stories Tolkien told, and extends no farther.

I’ve written elsewhere about how I thought the world of Star Wars was not defined by its story, but by the potential to be more than what appeared in the frame: here we have exactly the opposite relationship. Tolkien’s Middle-Earth is valuable to me precisely because it is defined by its stories, and not as a larger playground to fiddle around with. I love Star Wars video games and card games because it gives me an opportunity to futz around with the mechanics and ideas unmoored from the narrative; I am generally resistant to Lord of the Rings material because I don’t care to play in Tolkien’s playground without Tolkien at my side. To me, these properties were devised for different purposes. I respect that difference, and recognize that informs my interactions accordingly.

But Assassin’s Creed?

Screw Assassin’s Creed!

I could not care less what Magic does to/with the Assassin’s Creed property. This is perhaps the single most obvious example in my life of a world I care about only because of its central, overarching conceit: being able to hang out in historical locations with a loosely-affiliated gang of assassins unified by ideal over millennia. The actual games are a mixed bag: I don’t care a fig for getting the details exactly right. In fact, I’m pretty sure there are some major plot holes between the games themselves; clearly it’s not a priority for Ubisoft, so why should it be a priority for me, or Wizards of the Coast? So I am more than happy to let Magic ride roughshod over the mechanics of the video games, complimenting them when they get it right without criticizing when they miss the point. What do I care whether the card designers made Arno Dorian kind of bland and forgettable?—after all, Ubisoft made him kind of bland and forgettable first.

On some level, this may be one of the great mysteries (and paradoxes) of the hype cycle. I had absolutely zero expectations for this Magic set, and consequently have been pleasantly surprised at every turn. My disdain for both Magic and Assassin’s Creed has been transmuted into joy and excitement because of my low expectations and recognition that this is, frankly, trash. Corporate cash-grabbing at its lowest and worst. But because it is trash, with absolutely no aspirations or interaction with high art, I find myself able to enjoy it.

Let’s call this Met My Bottomless Expectations Hypothesis, for clarity. I’m tempted to alternatively call it the “How Did Donald Trump Win the Debate?!” hypothesis, but I expect that joke will be dated very, very soon.

So, You Spent $150 On Magic Cards Out Of Irony?

Well, no.

The Bottomless Expectations hypothesis doesn’t explain why I’m so dang excited about this set, but it does justify a very basic relationship to commercial trash, and forms a very interesting counterpoint to the Cyclical Stooge hypothesis. After all, Cyclical Stooge assumes a deep nostalgic connection likely rooted in reverence, where Bottomless Expectations assumes a kind of irreverence to the point of satire and irony. What I find interesting is that they can coexist so neatly together: I love some part of Magic’s essence and yet find it trashy and over-commercialized. I love the essential concept underlying Assassin’s Creed and yet find its execution frequently dumb and over-commercialized. And I think this is something important that we need to remember when we talk about fans and fan communities.

Much as I felt a bit out-of-place in my Distant Worlds concert, the temptation to judge the fans as gleefully indulging in some kind of commercial trash is wrong. Some fans do, I assume. Others discern between the good and bad entries in a property. Others still may have a mixed sense of love and disdain, as I do for Assassin’s Creed. It is more important to understand why someone likes the thing they do than it is to judge that they will uncritically continue to like the thing, just for the name alone. And popular things tend to provide for a multitude of needs, thus making it difficult to anticipate the fans’ overall reaction when changes are made. If it turns out that I like Final Fantasy music for its strong, simple melodies, it stands to reason that new, more harmonically-oriented orchestral soundtracks will alienate me, where others may find them more interesting or moving. Maybe it’s best if I get left behind on this one.

But that just raises the question: what, specifically, do I like about this weird, trashy set? What need does it fulfill?

And at this point we’ve gathered enough evidence to reach a pretty respectable conclusion.

Starting from the Bottomless Expectations hypothesis, we’ve made it clear that I have no reservations about liking this thing. I don’t have any reservations about the way Magic might reinterpret this thing I like, because I don’t like it that way—unlike The Lord of the Rings set. And since I have a pre-existing relationship with both properties, we can point to the Cyclical Stooge hypothesis as a reason why I might be watching out for something interesting to come out of this fusion.

But, at the end of the day, it is the fusion itself that I find so compelling. Not negatively or ironically, as a “ha-ha, this is dumb and I love it”, though there is a bit of that. But positively.

In short: Magic’s treatment of Assassin’s Creed gave me something I wanted from Assassin’s Creed, but couldn’t get.

What was that?

Let’s Talk About Super Smash Bros

Wait, hold on—don’t change the subject now! We were so close!

Come on, man. You think I spent this much time talking about a Socrates Magic card so I could not make my final point using a seemingly irrelevant concrete example?

Super Smash Bros. is a high-water mark in the history of commercial trash. It is a game where you take all your favorite Nintendo characters, abstract them completely from their proper context, and then have them beat the ever-living crap out of one another to the cheers of a crowd. It is a giant mess of conflicting art styles and play sensibilities, lovingly crafted into a demented (and thoroughly enjoyable) experience unlike anything you’ll find in the rest of video gaming. It’s dumb, pandering, and wonderful.

And by the most recent entry, Super Smash Bros Ultimate, it has become downright soulful in its elevation/devaluation of itself as trash. If you put down the controller and think, even for a moment, about what this game actually is, what it represents, you might give yourself an aneurysm.

It is also one of my favorite games, full stop.

And I think it’s pretty clear what the fans want from Super Smash Bros, in a way that is rarely clear among the otherwise-revered and beloved Nintendo properties SSB gleefully debases:

MORE.

Always, always more. More characters. More levels. More variety. More items. More modes. We want all the same characters we have now, plus the Adventure mode from SSB Brawl, plus sixteen simultaneous players, plus a Capcom vs. Marvel crossover—More More More.

Why?

Because we already like this thing: this game about beating random beloved video game characters senseless with zero attempt at contextualization. Because the game is, prima facie, fun, and we want more of our favorite things to Join the Battle.

This is not absolutely true. I don’t want a Samwise Gamgee Super Smash Bros character. I don’t even want a Star Wars/Super Smash Bros. crossover. But I’d be cool with Doomguy showing up, or Nathan Drake, or the nameless protagonist from Bioshock, or, indeed, Ezio Auditore.

On some level, this is all fair game, because all of these video game protagonists and characters are often comfortable with violence, the combat that informs these characters is typically enjoyable without context (it’s designed to be: that’s the core gameplay loop), and so we can freely translate it to this new, abstractly-violent context without any serious interruption in function. But translate a character defined by something other than a violent core gameplay loop (say, the character from Braid, or Phoenix Wright, or someone like Red Dead Redemption 2’s Arthur Morgan), and things will start to feel more wrong. Translate a character from a different, less-innately-violent medium (say, Darth Vader or Mickey Mouse), and it might feel even worse, even if those characters are, themselves, violent. We might be OK with a Darth Vader cameo in Soul Calibur, where the violence is treated with more seriousness and weight, but Super Smash Bros would be a bridge too far, I think.

So what gets translated when you bring your IP to Magic the Gathering?

Presumably the same core mechanics that always inform Magic: deckbuilding, strategy, and tactics.

Rethinking Universes Beyond

I think the primary error made by the developers of Magic in their translations of existing intellectual properties is that they aim to replicate the stories told in those properties. Sam and Frodo, Aragorn and Eowyn, Sauron and Saruman are reproduced in the hopes that you’ll be able to build your own story of temptation and overcoming danger—but that’s not something Magic can effectively replicate without some major mechanical overhauling, and both properties suffer.

But there is something truly exhilarating (to me at least) about turning Assassin’s Creed into a strategy game. About marshaling an army of Assassins from across time into a well-oiled engine of havoc and conquest. It fills a need I didn’t know I had, offers a perspective I didn’t know I wanted. In many ways, I’m more excited about this strange little one-off Magic set than I have been for an actual Assassin’s Creed game in years, and I don’t even think that’s weird anymore. I play Assassin’s Creed games to immerse myself in the historical worlds depicted there, and Magic cannot duplicate that; but Magic delivers on the underlying fantasy of organizing your assassins into a revolutionary force that the Assassins Creed games themselves cannot do without violating historical accuracy.

Suddenly I find myself wanting something like an Assassin’s Creed Tactics, or Pokemon-ish game, where it’s some far-flung future and some shadowy force is using a barracks full of Animus(es) to quickly train Assassins using their historical memories, abilities and techniques long forgotten. Maybe a time-traveling game, so we can use wildly disparate historical backdrops for architecturally-distinct urban combat arenas where Animus-trained Assassins and Templars duel for dominance over control of history itself. I want mechanics where you discover each initiate’s bloodline, which gives access to different abilities and skills: skilled sailors like Edward Kenway or Adéwalé from the Age of Piracy; orators like Socrates from Ancient Greece; fighters like Ezio or Altair; inventors like Leonardo or Galileo; strategists like Sun Tzu or Napoleon.

And as for Magic: I want more history. This foray into the human world has been fruitful in my opinion, but I want more. I want a Napoleon card, and a Julius Caesar card, and a Genghis Khan card, with mechanics that intersect and complement one another. I want Universes Beyond to quit trying to emulate the storytelling mechanics of something like Dungeons and Dragons or Lord of the Rings, and instead look to Age of Empires, Total War, or Civilizations for inspiration and emulation. Dune would be a very logical choice for a future installment, or even Wizards’ own Arkham Horror property. (And I’m suddenly wondering if that Warhammer set from a couple years back might be worth a second look…)

Let’s call this the Sweet Spot Hypothesis. Maybe I wanted something Assassin’s Creed had promised, but wasn’t willing to give—until they turned the reins over to Magic anyway.

…And Beyond

We live in the age of the multimedia empire. Disney owns half-a-dozen massive, sprawling Intellectual-Property-worlds; Amazon owns a streaming service, a gaming platform, several movie studios, and a network television channel. Comcast owns Universal, which owns NBC. This is just the basic state of the world in which we live. There are conversations to be had about the horrific economic state this promises to us, where monopolies in all but name jostle one another to control the same government agencies supposedly appointed to monitor and police them—but those are not the conversations I’m equipped or informed enough to have.

But I expect we’ll also be seeing the age of crossovers in the near future, if we aren’t seeing it already. Games like Super Smash Bros and Kingdom Hearts will become more normal—Disney’s Dreamlight Valley is already figuring out how to leverage Disney’s other holdings (like Star Wars, Marvel, or the Muppets) into their stable of characters. The Lego Batman Movie already played with a multitude of potentially-conflicting properties with significant success—and Lego itself is branching out into more and more properties with runaway profits (and I can’t even get upset about it…)

It’s going to be easy for some of us to get carried away in these sweeping decisions. We’ll want to get swept up in the excitement of translations, crossovers, and other IP developments. It’ll be easier still for some of us to throw tantrums about the fidelity of a new interpretation to an established brand or world. As creators, we’ll be challenged to find out how and when we can translate one medium into another, the rules of one world into the logic of a different one, and somehow keep the fans enthralled along the way. As fans, we’ll need to make decisions about where our boundaries lie: what can be commercialized, and what must remain sacrosanct—and that will require some pretty deep introspection about what it is we value about the things we enjoy.

But I say this like we have all that much choice in the matter. Sure, we can throw a fit, get angry in comments sections, make wild accusations or protest creators, but Amazon’s just going to keep making Lord of the Rings material, Disney will still insist on making Star Wars, and Magic will keep playing with IPs they don’t fully understand.

In which case, the question becomes: Can we be honest about what we like, and what we don’t?

Sitting in the Distant Worlds concert, or contemplating an obvious cash-grab Magic set, it’s easy to become dishonest with oneself. It is easy to prioritize some kind of elite and ambiguous sense of “taste” or “judgment” over the experience one is having in that moment. It is tempting to separate oneself from the “others”—the ones who are susceptible to commercialized pandering, while you, yourself, are immune. It is natural to sit there and justify your own choices while drawing lines between you and others.

I like Final Fantasy music, but those people have gone too far.

I don’t like crossover Magic expansions, but I’ll make an exception in this case.

I think that both the impulse to gatekeep, and the impulse to be open to new experiences are useful. But both have to be employed carefully. Boycott or protest a commercially-pandering and dubious choice from a corporation, and you run the risk of missing out on something interesting, exciting, or praiseworthy from whatever people (no matter how few) are trying their best to build something good out of cash-grabs and profit-motive. Protest too vocally and you could alienate others who like the new thing out of earnest and disinterested motives; protest too often, and you might find yourself habitually (cyclically) angry and resentful—which is, at the end of the day, just another form of crass commercialism, if the success of so many angry YouTubers is any indication.

But grow too open, too accepting, too forgiving, and you’ll find yourself wasting your time on undeserving enterprises. You will lose hours to video games you don’t enjoy or movies you find unsatisfying in the name of completionism or loyalty, while other, more inventive and deserving projects go ignored. Defend a work too enthusiastically, or for the wrong reasons, and you’ll end up enabling lazy practices from already-bloated corporations, justifying their conviction that they can sell an inferior product if they just market it the right way. At worst, you may find yourself howling against critics for putting down a thing you’ve loved unjustly, railing against poor reviews as you transmute a sunk cost into unjustified rage.

Art is meant to inspire reflection. Always. Insofar as it fails to do this, it stops being art and becomes mere polemic: like the objectivist screed in Atlas Shrugged or shallow Christian apologetics in Tolstoy’s Resurrection. More relevant to our discussion, we should be wary of the techniques corporations use to manipulate us into acting without reflection: the merry electronic music that makes a slot machine so enticing, artificial card scarcity to drive up prices and encourage mass, indiscriminate purchasing, and all the cheap advertising techniques surrounding the release of a new video game.

We must learn to discern the difference between the good and the bad, the benign and the pernicious. We must learn to step back from the excitement of the things we love and ask these questions of ourselves: what do we like about this? Why does this or that change make us angry or excited? How are we being manipulated, and how does that manipulation affect us? Magic the Gathering as artistic enterprise, as social venue, as mechanical test of skill—all of these things are good, and add value to this storied game. Magic as opportunity for competitive dominance, as socially-approved gambling, as psychological trap for the obsessive and gullible—these things are dangerous at best, manipulative and cruel at worst.

Today I think I gave a very commercial product far too much benefit of the doubt in using it as a catalyst for understanding myself. But it did check me in my assumptions, and I will, however begrudgingly, admit that I enjoyed this crass thing, and hope to enjoy it even more going forward. If anything, I question the grudge. I don’t think it is art for this reason, because I doubt anyone over at Wizards of the Coast wanted me to think through all the stages of resentment and acceptance I experienced. This was not a desired reaction, I suspect, though it may be an acceptable one (all publicity is good publicity?).

But even at its worst, there is art to be found, even in something as crass, exploitative, and commercial as Magic in 2024, and I don’t fault anyone who has enjoyed any of the sets or releases I’ve denigrated in this essay. Maybe they found something they wanted in an unlikely place, just as I did.

We can also expect better, though, and should.